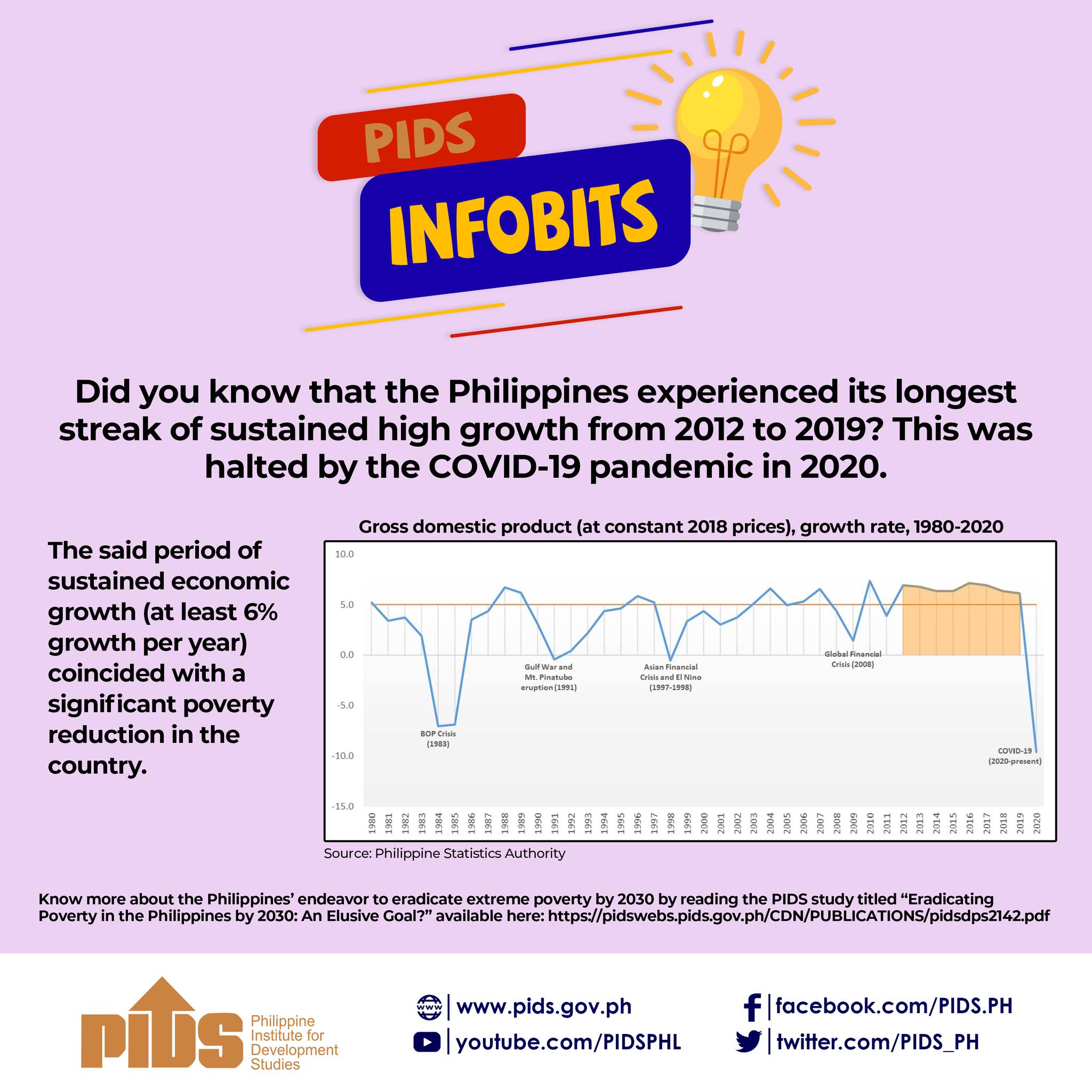

DELAYS in vaccinating the majority of the population as well as the challenges posed by poor containment measures against Covid-19 will lead the Philippine economy to post growth of below 6 percent until 2023, according to the World Bank.

The World Bank’s East Asia and the Pacific Update saw its GDP growth estimates for the Philippines decline 1.2 percentage points to 4.3 percent in 2021 from the 5.5-percent forecast made in April.

The World Bank also cut its projection for 2022 GDP growth to 5.8 percent in September from the 6.3-percent forecast made in April. Growth is still projected to reach 5.5 percent in 2023.

“[The Philippines] is a country that suffered enormously because of Covid. It has some of the largest declines in growth forecasts that we have predicted and we do see the challenge. This is a country that supplies the world with medical staff and nurses and it is a particular tragedy that domestically it has not really succeeded,” World Bank East Asia and Pacific Chief Economist Aaditya Mattoo said in a briefing on Tuesday.

“But it’s not just a difficulty of policy. The Philippines remains highly vulnerable to natural disasters and those are not easy to deal with,” he added.

The World Bank estimates that the Philippines and Indonesia will only be able to achieve more than 60-percent vaccine coverage by June 2022.

This amid the challenges posed by “limited global production capacity and the decision to provide booster vaccines in industrial countries.”

This year, China, Mongolia, Fiji, Cambodia, Malaysia, Tuvalu and Thailand will be able to reach vaccine coverage of over 60 percent while Samoa, Tonga, Lao PDR, Timor-Leste, Vietnam, and Kiribati will get there by the first quarter of 2022.

Countries such as Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Myanmar and Papua New Guinea are expected to reach 60-percent coverage by the third quarter of next year or beyond.

“The Philippines again had a problem of vaccine hesitancy. It had not acquired enough vaccines, it was late into the vaccine market. But the good news, as I said, we project that even the Philippines by the middle of next year will have high levels of [vaccine] coverage,” Mattoo said.

“What does it take to save lives? It’s to learn to live with the disease. [There is a need to] strengthen the health system, learn to provide the care that is needed, when it is needed,” he added.

Poverty, inequality

For the first time, Mattoo said the EAP region is expected to have both slow growth and widening inequality. This is a “reversal of fortune” for the region as many of the countries suffer as much as 2-percentage-point reduction in growth prospects.

The report said this slow growth and greater inequality will lead to more people being unable to leave poverty such as in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Myanmar. The World Bank said 90 percent of those who will remain poor in Asia would come from these countries.

In the Philippines, the World Bank said poverty would decline 2.1 percentage-points more slowly, and the economically secure class would grow by only 2.9 percentage points compared to 4.8 percentage points.

This represents 2.4 million fewer people escaping poverty and 2.1 million fewer people rising into economic security in the Philippines by 2023.

Inequality in the country is also expected to worsen. The World Bank said this may have already begun as governments, including that of the Philippines, extended uneven assistance among firms.

The World Bank said that half of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) in the region have not received any form of support from governments as of the last quarter of 2020, and less than 20 percent of very large firms missed out on support.

Inequality today will, the World Bank said, “hurt growth tomorrow.” In the Philippines, inequality could lead to child malnutrition, compounding the already high level of stunting in the country.

The World Bank noted that stunting the Philippines is associated with a lower likelihood of formal employment. It found that “a 1-centimeter increase in stature is associated with a 4-percent increase in wages for men and a 6-percent increase in wages for women.”

Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) Senior Research Fellow Valerie Gilbert T. Ulep said the common belief that Filipinos are “short” may not only be due to genetics, but could have been caused by malnutrition.

“For many years, we tried to normalize stunting—that it is part of [what] we are, it’s part of our genetics, etc. But I think we need to reflect on that because it might be something else. It might be a reflection of chronic malnutrition more than a reflection of who we are as Filipinos, Ulep earlier said in this story: https://businessmirror.com.ph/2021/09/25/coming-up-short-on-sdg/.

His conjecture was supported by one of the project evaluation studies of the National Economic and Development Authority (Neda).

In the Formative Evaluation of the Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition (PPAN) 2017-2022, Neda found that only a few Filipinos related stunting to nutrition.

“Widespread misconception on stunting among the respondents was observed as the majority mistakenly believed that stunting is hereditary and Filipinos are short by nature,” the report stated.

The region

The World Bank said East Asia and Pacific region’s recovery has been undermined by the spread of the Covid-19 Delta variant, prolonging the distress for firms and households, likely slowing economic growth and increasing inequality,

While China’s economy is projected to expand by 8.5 percent, the rest of the region is forecast to grow at 2.5 percent, nearly 2 percentage points less than forecast in April 2021.

Employment rates and labor force participation have dropped, and as many as 24 million people will not be able to escape poverty in 2021.

“The economic recovery of developing East Asia and Pacific faces a reversal of fortune,” said World Bank Vice President for East Asia and Pacific Manuela Ferro. “Whereas in 2020 the region contained Covid-19 while other regions of the world struggled, the rise in Covid-19 cases in 2021 has decreased growth prospects for 2021. However, the region has emerged stronger from crises before and with the right policies could do so again.

Damage from the resurgence and persistence of Covid-19 is likely to hurt growth and increase inequality over the longer-term, the Update finds. The failure of otherwise viable firms is leading to the loss of valuable intangible assets, while surviving companies are deferring productive investments.

Smaller companies have been hit the hardest. While most firms have faced difficulty, larger firms are likely to see a smaller decline in sales and more likely to adopt sophisticated technologies and receive government support.

Households, especially poorer ones, have suffered. The poorer ones have been more likely to lose income, suffer greater food insecurity, have children not engaged in learning, and make distress sales of scarce assets.

The resulting increase in stunting, erosion of human capital and loss of productive assets will hurt the future earnings of these households. Increased inequality between firms could also increase inequality between workers.