A group of farmers, fishers, civil society organizations, and the private sector has expressed opposition to the ratification of the world’s largest free trade agreement—the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

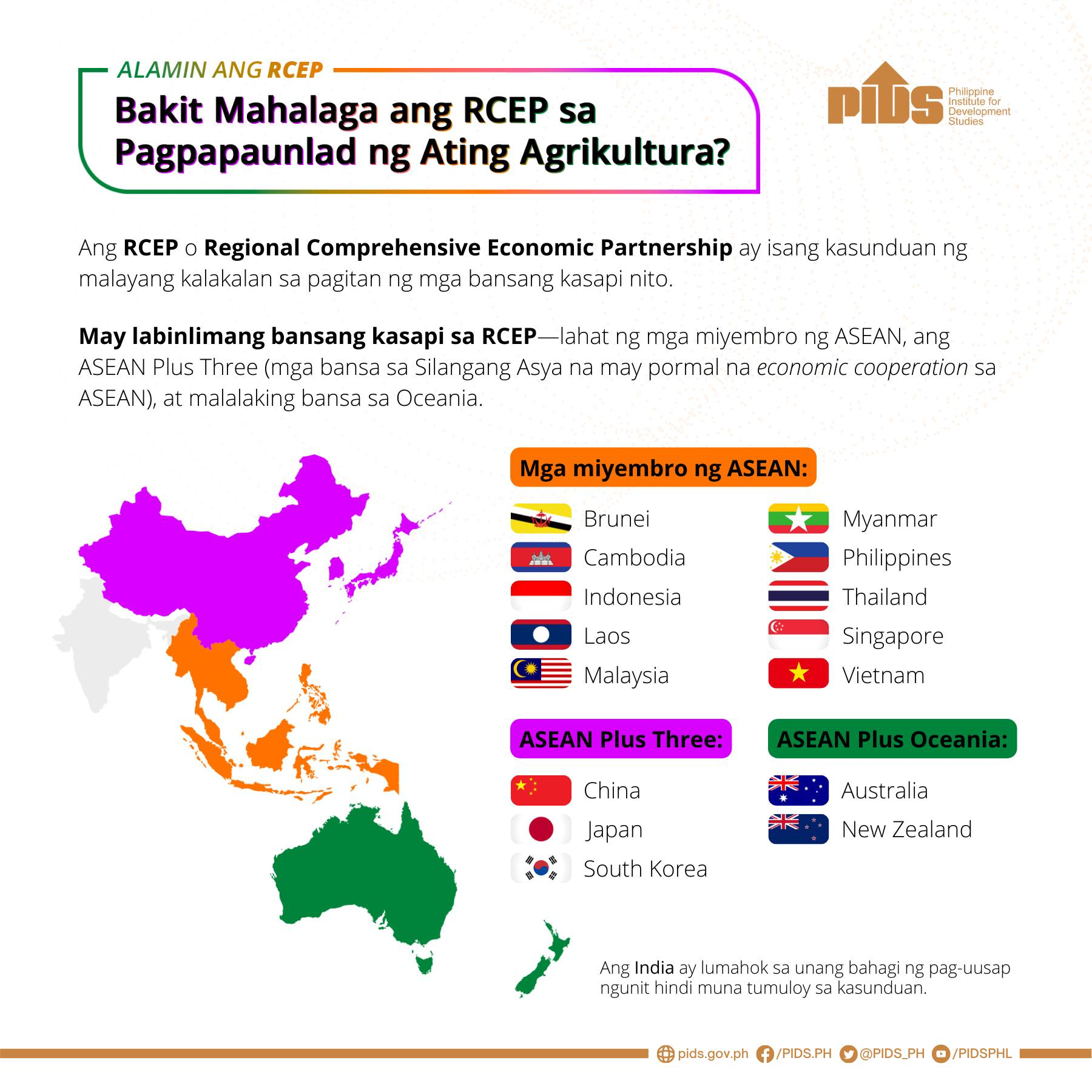

The Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Brunei—and trading partners China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand—have signed the multilateral trade pact last year, in hopes of reviving their economies following the ravage of COVID-19.

According to the ASEAN Secretariat and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), the multilateral trade pact aims to “achieve a modern, comprehensive, high-quality, and mutually beneficial economic partnership agreement” among ASEAN member states and ASEAN’s free trade partners.

RCEP will cover trade in goods, trade in services, investment, economic and technical cooperation, intellectual property, competition, dispute settlement, and other issues.

However, a position paper issued by the Federation of Free Farmers (FFF) urged the Senate to defer concurrence on the free trade pact due to a lack of consultation with farmers and other stakeholders.

“The RCEP agreement, including its legal text and schedule of Philippine commitments, was finalized without consulting agri-fisheries stakeholders, many of whom are directly affected by the treaty’s trade rules and concessions,” said FFF national manager Raul Montemayor in the FFF paper.

“Moreover, no more opportunity exists today to modify our commitments or the legal text of the agreement,” he added.

Opposing the ratification

According to the DTI, the free trade area accounts for 29 percent of world trade, 29 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP), 33 percent of global inward foreign direct investments (FDI), 47 percent of global outward FDI, and 2.3 billion population.

The DTI also said the RCEP accounted for 51 percent of the Philippine export market and 68 percent of Philippine import sources in 2020 as well as 58 percent of FDI source in 2020.

The free trade agreement aims to make products and services available to the ASEAN member states and FTA partners. It will also eliminate a range of tariffs—taxes imposed on goods and services imported from another country—within 20 years.

The FFF, however, said it has not seen “any clear and consistent basis for classifying agricultural tariff lines in the country’s schedule of tariff concessions.”

The group said as it is written, RCEP could lead to 75 percent of the Philippines’ 1,718 agricultural tariff lines to be set to zero.

The FFF paper also pointed out that at least 15 percent of tariff lines will be subjected to tariff reduction, while nine percent will be exempted from any tariff change.

The FFF position paper also warned about proposed RCEP rules which “will significantly hamper the application and effectiveness of trade remedies.”

These rules included safeguard duties, which the FFF said will be the “only legal recourse” to address problems triggered by RCEP—such as import surges.

According to data from the Bureau of Plant Industry (BPI), at least 1.99 million MT of rice arrived in the Philippines from January to September 2021.

This was 7,000 MT short of 2020’s import volume ceiling of 2.06 million MT.

The bulk of imported rice, which is supposed to be sold at a cheaper price in the market, has impacted Filipino farmers. Some farmers are left barely surviving with little to no income as production costs stood at around P12 per kilo.

The FFF said under RCEP, several existing policies on importation were likely to be thrown out.

This included quantitative restrictions (QR), which sets volume ceilings on importation of produce that are also being grown in the Philippines. Another is sanitary and phytosanitary import clearances which are required to prevent agricultural pests or infestation from entering the Philippines.

While World Trade Organization rules would still allow QR ceilings, FFF said these were only for “certain critical situations.”

“RCEP limits the allowable safeguard duty to the difference between a country’s applied most favored nation (MFN) tariff at any point during RCEP implementation and the RCEP tariff in effect when the safeguard remedy is invoked,” the FFF added.

This means that if there is a 35 percent applied MFN tariff for a product and the country’s commitment under RCEP is 25 percent, the government can only impose a safeguard duty not exceeding 10 percent when an import surge occurs.

“Hence, sensitive products like rice, corn and some fishery and livestock products–to be exempted from any tariff reduction under RCEP-might ironically be deprived of any safeguard protection, since their tariff at any time during RCEP implementation could already equal their applied MFN tariff,” the FFF said.

The proposed limits under RCEP, according to the FFF, “is a big departure from WTO rules, which permit the levying of any remedial duty necessary to prevent or rectify serious injury to a particular sector.”

The organization also added that imports from Myanmar, Cambodia, and possibly Vietnam–among the least developed countries in ASEAN–can not be subjected to safeguard duties under the multilateral agreement.

“No such exemption exists under WTO rules.”

Last May, President Rodrigo Duterte issued Executive Order No. 135, which temporarily reduces most favored nation (MFN) tariffs for rice to 35 percent from 40 percent for in-quota imports (those on the most favored list) and 50 percent for out-quota imports (those outside the most favored list).

The EO had been denounced by FFF, describing the reduction in rice import tariffs as “totally unjustified.”

RCEP was first introduced in November 2011 during the 19th ASEAN Summit in Bali, Indonesia. The negotiations commenced in early 2013 and were concluded last year.

“In the past, the bullish predictions of free traders and their dire warnings about non-accession swayed Congress to concur with almost every trade agreement,” the FFF said.

“We hope the Senate will not give the Executive another free pass, considering that the benefits of liberalized trade have generally not been realized,” the group added.

‘Theoretical’ benefits

Trade Secretary Ramon Lopez said RCEP will play a role in boosting equitable economic growth, including for MSMEs, through the expansion of regional trade, services and investments linkages.

Lopez said the benefits brought by the trade agreement to the country “far outweigh the cost of not joining.”

“The RCEP provides for a framework aimed at further lowering trade barriers, and securing improved market access for goods and services for businesses in the region characterized by a 2.3 billion USD potential consumer base, and a collective GDP that makes up almost 1/3 of the world’s GDP, global trade, and global inward foreign direct investments,” said the trade chief.

“The benefits of the RCEP Agreement to the Philippines far outweigh the cost of not joining. We urge for the Senate’s concurrence of RCEP within the year to allow the country to be a part of this largest free trade area and to ensure that we take advantage of this mega deal to facilitate post-pandemic economic growth,” he added.

RCEP Lead Negotiator, Assistant Trade Secretary Allan Gepty detailed the key benefits of RCEP for the Philippines, which could be summarized into 3Cs, namely: cheaper costs for sourcing key inputs of the manufacturing sector; competitiveness for Philippine industries; complementation of existing government support programs.

“The RCEP provides business-friendly mechanisms to facilitate trade with the country’s key trading partners through clear and transparent procedures,” Gepty said.

“Together with a secure market access for cheaper raw materials and intermediate goods to sustain and improve its export and local industries, Philippine exports can also avail of flexible certification procedures (e.g. Certificate of Origin) that will make it easier for businesses, especially MSMEs, to use the FTA and avail of the preferential arrangement,” he added.

These “rosy projections on benefits” from the trade agreement, including the expected losses to be incurred by next year if the country will stay outside the trade bloc, were questioned by the FFF.

“We have heard such claims before, starting with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)-Uruguay Round Agreement and the various regional and bilateral trade agreements that followed,” the FFF position paper read.

“We still have to see evidence that these optimistic forecasts have materialized,” it added.

Francis Mark Quimba, a research fellow from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), was quoted in an article by the government-run Philippine News Agency (PNA), as saying that the country could lose two percent in GDP growth if the government fails to ratify the RCEP.

“Aside from missing out on the 2 percent growth in GDP, we will experience 0.26 percent decline if other countries will proceed and we’ll be left behind,” he added.

FFF said that despite the trade pacts entered by the country in the past, data showed continuing deterioration in the country’s trade system—which included the minimal rise in exports, no expansion beyond traditional commodities, the surge in imports, and widening trade deficits.

The organization also described the benefits of the “good agreement” under RCEP as “essentially theoretical or imagined.”

Meanwhile, the dangers of the trade deal are real and proven by previous experience.

“Nor is there any indication that our prospects will improve under RCEP,” the FFF said.

“We therefore deem the claims regarding benefits from RCEP membership as overly presumptive, highly misleading and manifestly deceptive,” the group added.

“We will never gain from RCEP and similar arrangements unless we establish, fund and implement dedicated and sustained programs to boost the competitiveness and profitability of our farmers, fishers, traders, processors and exporters.”

Agri-fisheries: biggest losers

“The agri-fisheries sector has generally not benefited from business opportunities arising from free trade agreements, while our competitors have increasingly dislodged us from export markets with superior and cheaper products,” FFF said.

“In turn, our entry into these trade pacts has forced us to open up our economy, even as we have failed to prepare for trade threats—resulting in import surges, price depressions, and displacement of local production,” the group added.

According to Ibon Foundation, poverty incidence among farmers was 31.6 percent and 26.2 percent for fisherfolk—both much higher than the national average of 16.7 percent.

A statement by FFF, Bayanihan sa Agrikultura, Alyansa sa Agrikultura, Coalition for Agriculture and Modernization in the Philippines (CAMP), Philippine Chamber of Agriculture and Food Inc. (PCAFI) also said three in every four poor Filipinos are in rural areas.

“Limited number and quality of job opportunities. Hence, big development disparity between rural and urban areas, and mass exodus to urban centers remains unabated,” the groups said.

“Under the Duterte administration, an average of 328,000 agricultural jobs were lost annually from 2017-2020, which is the worst among the last six administrations,” the groups added.

No need to rush

The FFF argued that there was no urgency in joining RCEP immediately and that the country can always join later, “when we have adequately understood the treaty’s ramifications and are ready to use RCEP membership to our advantage.”

“Trade is not a race of countries to a finish line. Ultimately, trade is only a means to elevate people’s lives,” the FFF position paper stated.

“Governments must thus exercise care and deliberation, so that trade agreements deliver on their promises, while minimizing harm to vulnerable sectors of society,” it added.

FFF said the country can still enjoy trade opportunities outside RCEP through negotiations with FTA partners, which can also help secure additional advantages—on the basis of equality, reciprocity, mutual benefit, and national interest.

Ernesto Ordoñez, former agriculture and trade undersecretary and columnist of the Philippine Daily Inquirer, said that rushing to enter trade agreements without due diligence could possibly result in the death of businesses, further job losses, and a significant increase in poverty.

“Is RCEP hurtful to our citizens, and should we therefore opt out of RCEP like India did? If due diligence has not been done, our Senate should postpone the RCEP concurrence decision until the required work is done,” Ordoñez wrote in a column piece published on Nov. 5.

India was originally a member of the RCEP drafting committee in 2011 but in 2019, the country opted out of the agreement citing some main concerns that were left unaddressed.