THE end-stage talks to form the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the Chinese counter to the now virtually dead Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), hit a few snags during this week’s Asean summit in Singapore, and will not be completed until next year at the earliest. While the Philippines is officially supportive of the RCEP, it should use the extra time to carefully reconsider its position and press for more favorable conditions.

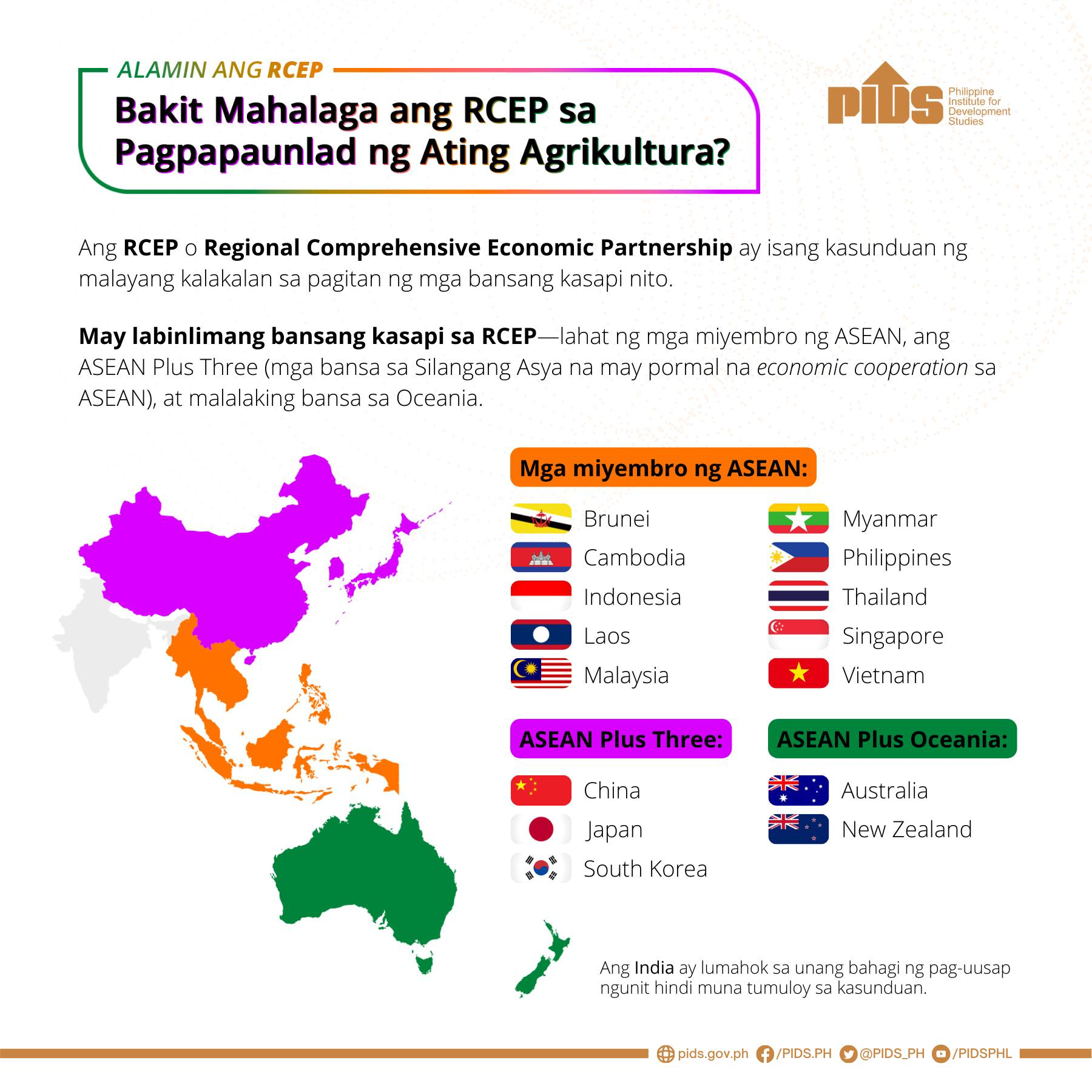

In a statement that he obviously didn’t write himself, President Rodrigo Duterte told the other participants in the RCEP — the 10 Asean members, plus China, Japan, India, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand — that “amid prevailing uncertainties in the global economy, we must continue supporting the rules-based multilateral trading system. Trade actions contrary to this benefit no one and only threaten the prospects of economic growth.”

The statement was a clear shot at the US, whose president Donald Trump pulled out of the TPP as one of his very first actions in office, and has thrown world trade into chaos by starting a tariff fight with just about every major trading partner America has. Trump deserves every shred of criticism that can be thrown his direction, but in terms of tangible responses, going all-in on the RCEP seems a dubious choice. As it is designed, the RCEP for the Philippines appears to simply represent the substitution of a trade framework favoring one economic overlord for another.

The basic premise behind the RCEP, being a Chinese invention, is to provide a stable trade environment for China. China needs raw materials and agricultural products, and needs markets for its finished export goods and technology. Unlike Western-based trade frameworks like the WTO, there is little political idealism in the Chinese initiative, and that is part of what makes it attractive; China just wants to do business, not tell others what sort of moral code to adopt. On the face of things, the RCEP is a good deal for countries like the Philippines. You’ve got bananas or coal to sell? China will buy them. You need new cell phones, bridges, or energy technology? China will sell them to you for a good price.

While the RCEP is styled as a regional trade arrangement — the rules that are agreed between any one participant and China can be applied to trade between any two other participants — the needs of China and its huge domestic economy are still the reference point. As long as the Philippine economy stays just as it is now — driven primarily by consumption, with some contribution from first-level productive inputs – the Philippines will subsist quite nicely, and will continue to put on the appearance of a “robust economy.”

But while that may be good enough for the 5 percent in the upper crust of Philippine society and expats who view their continued ability to live a colonial lifestyle as a reasonable indicator of the Philippines’ economic health, that state represents a plateau. This country is large enough and has the resources to aspire to being something better than a permanently “emerging market.” In order to achieve a higher state, however, the Philippines needs to accomplish two rather big objectives: Create and expand a more diversified industrial base, and expand its agricultural output.

Neither of these objectives is a mystery. A recent report from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) pointed out that the Philippines’ export product profile has not changed in 20 years, which is a fairly good indication that the industrial base hasn’t evolved in that time, either. And in terms of agriculture, the sector is still under-producing by a factor of three – it contributes roughly 10 percent to GDP, but takes roughly 30 percent of the country’s labor resources to do so.

The RCEP is not going to help the Philippines advance either of its great economic growth objectives. It is certainly not in China’s best interests that a potential industrial competitor develops in a part of the world it considers its market and sphere of influence. And while China may not have much of a problem with the Philippines diversifying and improving the productivity of its agriculture sector, the Philippines’ competitors for the Chinese market will, and the final terms of the RCEP will impose conditions on everyone that prevent any country from advancing too far.

Not taking part in the RCEP is probably impractical, as the Philippines will be at an even bigger disadvantage in terms of trade. In any event, President Duterte has already made obeisance to Chinese authority in the region the rudder of Philippine policy, so debating whether or not the Philippines should take part in the RCEP is moot. But the Philippines must approach the final negotiations with a view toward the country’s long-term economic needs, and not accept conditions that are going to prevent the future leadership of the country from working to achieve them.