Malnutrition has dogged the Philippines for decades from the malnourished children during the Negros famine in the 1980s to today’s stunted children whose future in an increasingly competitive world is in peril.

Last week, the government announced it has borrowed P10 billion from the World Bank to fund the four-year Philippine Multisectoral Nutrition Project (PMNP) aimed at lowering the incidence of malnutrition. A lawmaker has called PMNP the “most aggressive program” yet to combat malnutrition and stunting in poorer municipalities. This new program, targeting 235 towns, aims to assist communities by providing children and pregnant mothers with primary health care services and nutritional support.

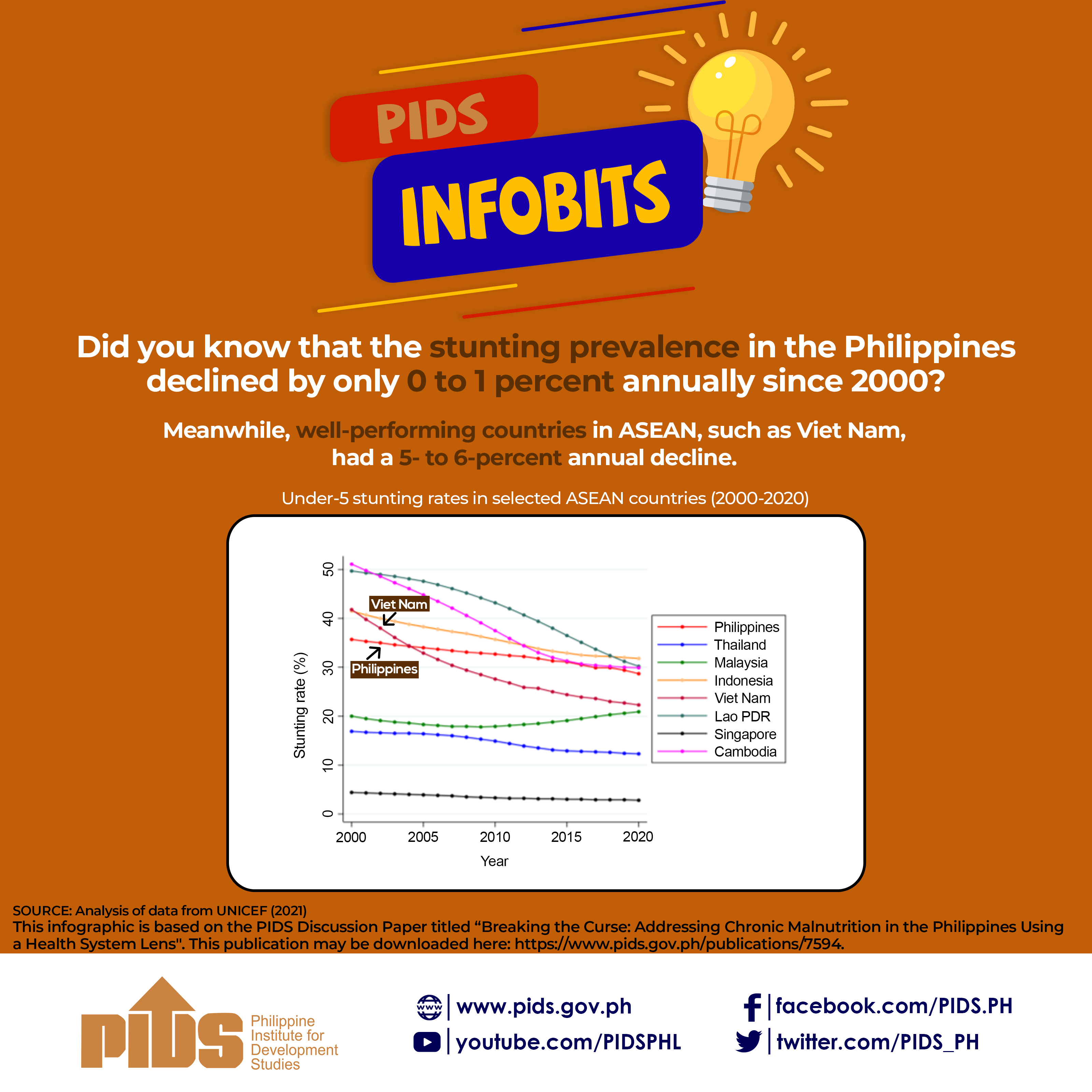

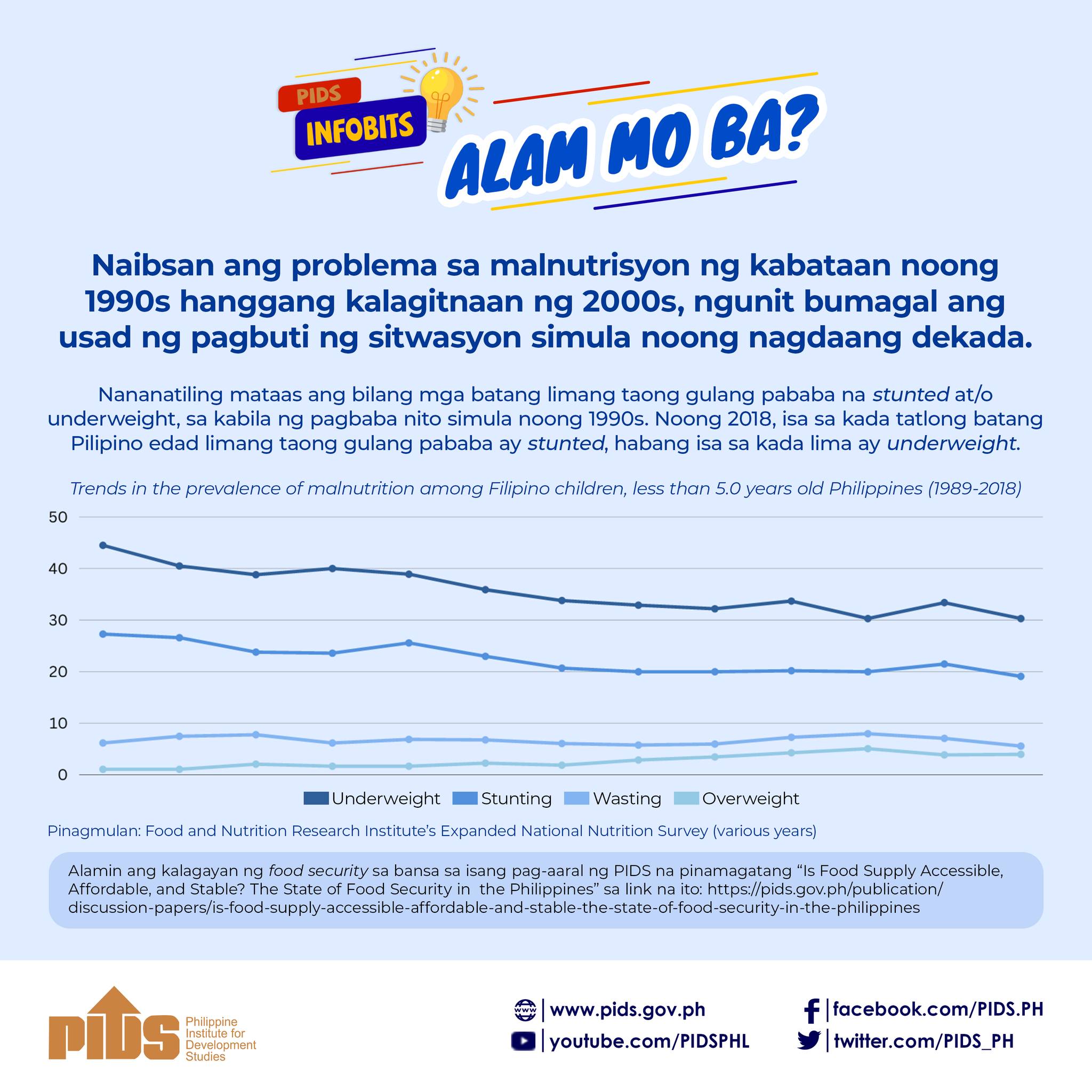

For nearly 30 years, the World Bank said, undernutrition has remained a serious problem with one in every three Filipino children below 5 years old suffering from stunting or “pagkabansot” (being small in size for their age). The country ranks fifth among countries in the East Asia and the Pacific region with the highest prevalence of stunting. Malnutrition, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund, also kills 95 Filipino children every day, while 27 out of 1,000 do not get past their fifth birthday.

Because of the huge human and economic costs, malnutrition deserves to be among the country’s top national priorities together with other urgent issues such as poverty, climate change, and national security. Its impact extends over generations: Undernourished children are more likely to face death in their early years, and if they survive, they are likely to perform poorly in school, which will affect their future as adults, including the jobs that they will get. In other words, a generation of undernourished children will result in poorly performing adults who will perpetuate their poverty and will not have the necessary skills to better their lives and contribute to the country’s human capital. This will make it harder for them to get out of the vicious cycle of poverty, malnutrition, illness, and poor health.

“Studies have shown that children who were not able to achieve optimum growth within their first 1,000 days from conception are at higher risk of impaired cognitive development which have adverse effects on their schooling performance, labor force participation, and productivity in later life,” the 2015 study, “Sizing up the stunting and malnutrition problem in the Philippines” by Save the Children, stated.

The extent of this problem can already be seen in the poor performance of Filipino students in the 2018 Program for International Student Assessment or Pisa where they ranked the lowest among 79 countries in mathematics, science, and reading. The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the learning gap and this education crisis, if not immediately addressed, will affect the country’s skilled labor force, make it unattractive to investors, and hamper economic growth.

About 62 percent of the country’s labor force, per a study by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, are working in service or clerical occupations that only require social and basic skills, as well as lower analytical skills. But developments in the information and communications technology sector have reshaped the labor force and demand more intensive use of ICT, data analytics, and highly specialized skills. Tertiary education becomes even more crucial in providing young Filipinos with the necessary cognitive and noncognitive skills so that they are ready for future demands.

But what happens if a third of today’s children below five years old are unable to get the proper nutrition hampering their mental and physical development? These are the children who are likely to be deficient in nutrients such as iodine and will have lower IQ, start school later, perform poorly on cognitive functioning tests, and worse, drop out of school because they cannot keep up—let alone reach the tertiary level of education. These are the children who will grow up as adults likely to live in poverty and less likely to develop skills that would enable them to get better jobs. And these are the children whose future children will suffer the same fate unless government intervention reaches them.

Malnutrition is not only a health problem or a current issue—it is an economic problem whose effects can be felt for generations to come. It is important for the government to effectively and judiciously use PMNP’s multi-billion funding to provide for the health and nutrition needs of poor mothers and their children. Let it not be another one of those government programs that will end up corrupted with millions of Filipino children suffering from the irreversible damage of undernutrition while the pockets of a few are fattened.

Ensuring that PMNP achieves its goals will help build the country’s human capital that it needs to drive the economy and give it a competitive edge on the global stage. That will be a very cost-effective investment for the country’s future health.