The Philippine Health Insurance Corp’s (PhilHealth) membership-to-population coverage in the poorest provinces is only a little over half of the target 100-percent healthcare coverage guaranteed by the Universal Healthcare Act (Republic Act [RA] 11223), according to a study of state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

In “Spatiotemporal Analysis of Health Service Coverage in the Philippines,” authors PIDS Senior Research Fellow Valerie Gilbert Ulep, Supervising Research Specialist Jhanna Uy, and research consultants Clarisa Joy Flaminiano, Vicente Alberto Puyat, and Victor Andrew Antonio examined the health service coverage, including membership coverage, at the provincial level.

It is one of the first studies to use PhilHealth data on insurance claims, membership, and accredited facilities from 2018 to 2021, combined with auxiliary datasets from the Department of Health (DOH), Philippine Statistics Authority, and Washington-based Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation to identify location-specific trends and insights.

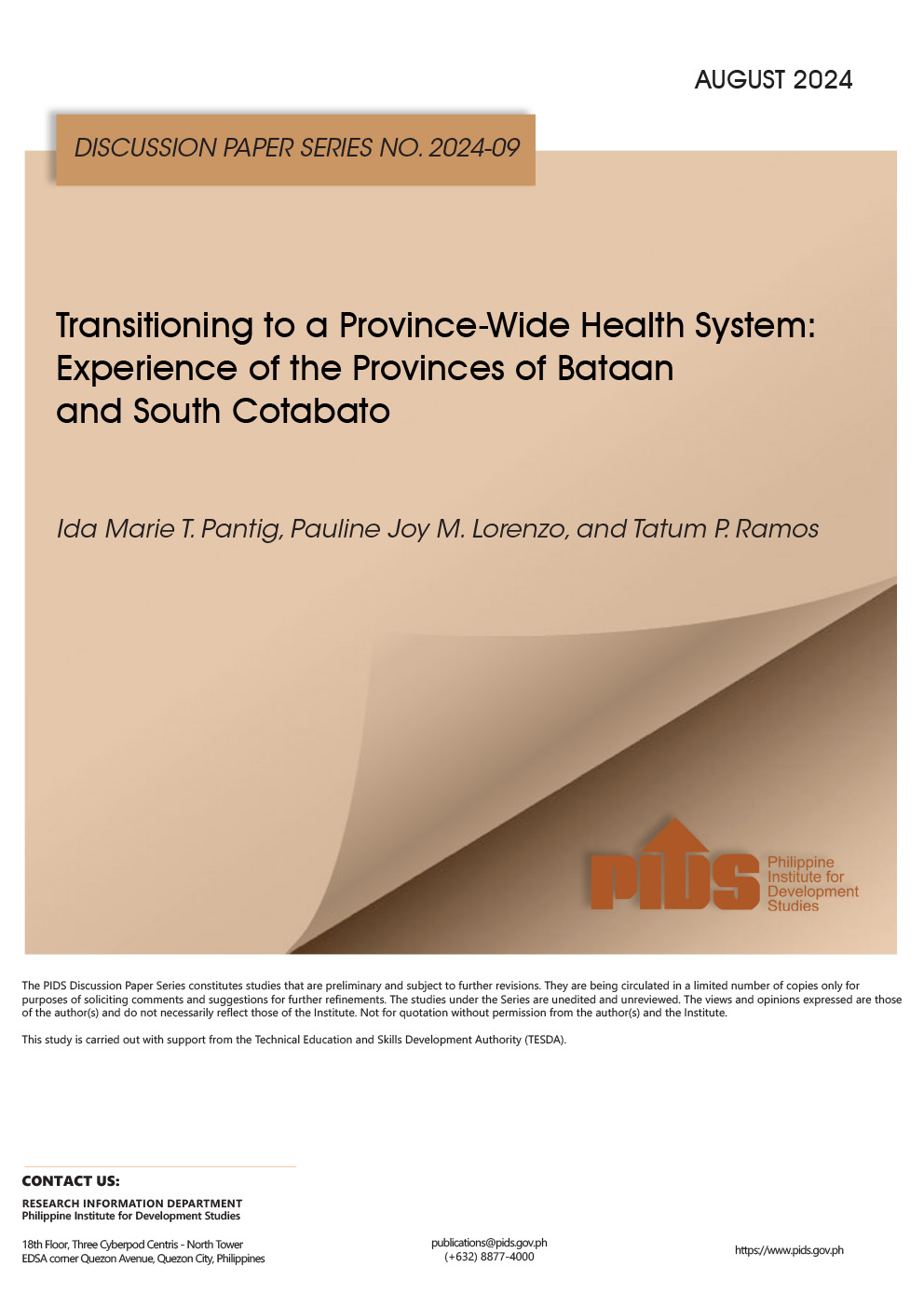

The study observed that PhilHealth’s population coverage was high in most island groups, but some provinces had only over a 50-percent coverage, which must be prioritized to achieve universal PhilHealth coverage.

“RA 11223 states that all Filipinos are automatically enrolled under the National Health Insurance Program—which makes the PhilHealth [target] coverage rate 100 percent. But after looking into PhilHealth’s registered beneficiaries data from 2018 to 2021, we identified geographic discrepancies in the population coverage across provinces,” the authors said.

National Capital Region and Regions III and IV-A (98.9%), Luzon (90.7%), and Visayas (90.5%) have high population coverage. Mindanao follows close behind at 87.82 percent, but five of its conflict-affected provinces, namely, Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur, Basilan, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi, registered the least PhilHealth coverage at 52 percent and below.

Mindanao also has the largest share of indirect contributors, mostly indigent or sponsored, at 57 percent. Indigents and beneficiaries of government programs like the Pantawid Pamilya Pilipino Program are said to be “at higher risk of contracting diseases”.

The study also found that the poorest provinces have low population coverage, with senior citizens, indigents, or sponsored beneficiaries mostly as members.

Ulep and co-authors explained that the disparity in PhilHealth coverage in urban and rural areas is driven by many factors, including employment, poverty incidence, wage rates, and process inefficiencies in the classification and enrolment of indigents and sponsored members. They added that the urban-rural disparity is echoed by healthcare studies abroad.

Filipinos living in rural areas also have fewer options for healthcare services because PhilHealth-accredited facilities are “disproportionately located in urban areas”.

According to the authors, PhilHealth, DOH, and relevant stakeholders must focus on improving healthcare coverage in the poorest provinces and among indigents in poor urban areas to achieve universal healthcare. To address the disparity, they recommended improving the PhilHealth membership enrolment, especially in priority areas like Mindanao, where lower membership rates may be due to enrolment not being adjusted to provinces’ socioeconomic conditions.

For provinces with low poverty incidence that tend to have high membership coverage, the authors suggested expanding the healthcare coverage to their poorest areas.

They also emphasized using standardized equity measures—such as poverty incidence—in national allocation and prioritization frameworks of projects and activities for equity and efficiency across health programs. “PhilHealth, in collaboration with other government agencies, must ensure the accuracy, validity, and consistency of data on indigents at both national and subnational levels to improve healthcare equity throughout the country,” they said.