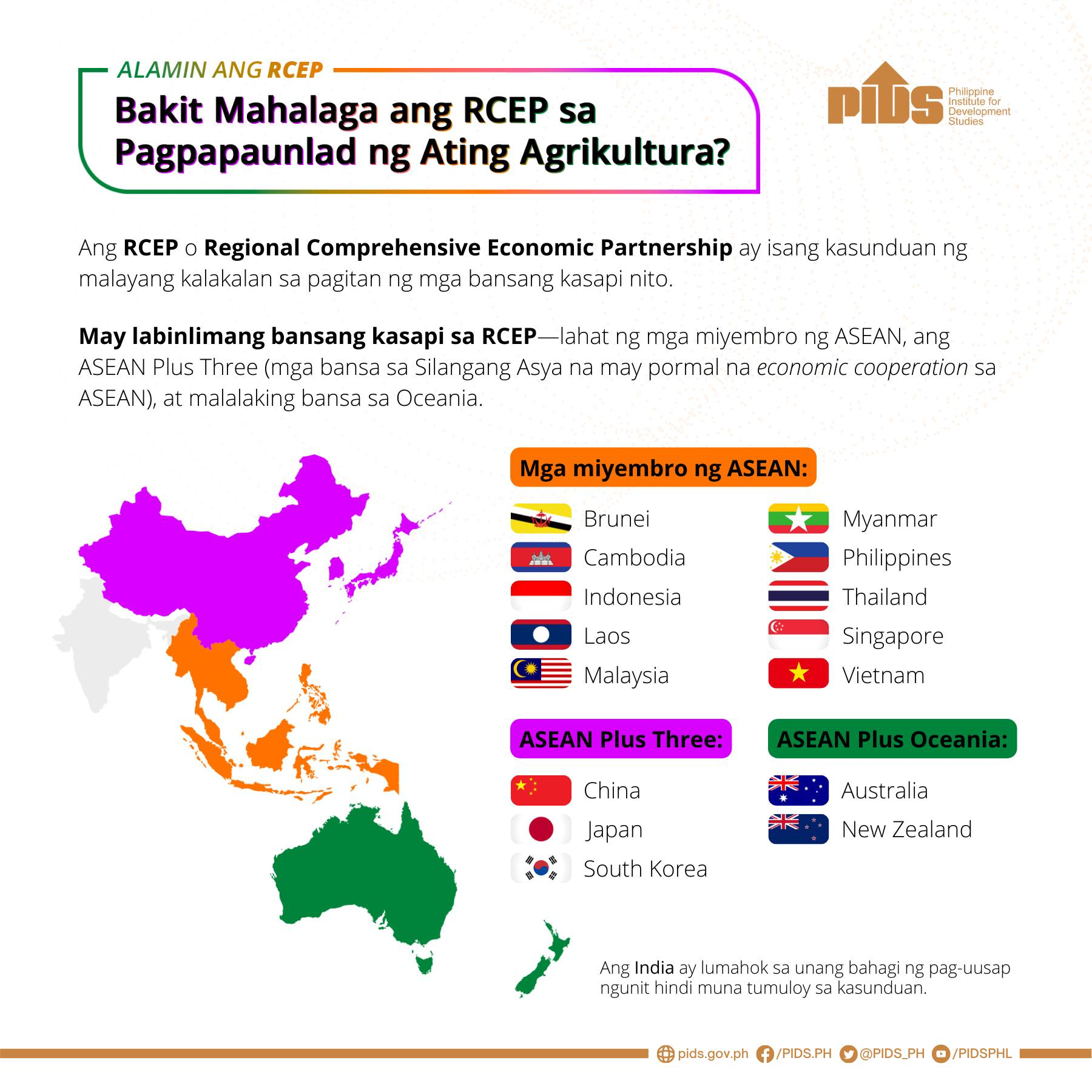

What exactly is the RCEP?

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) is a 15-country multilateral free trade agreement (FTA) involving the ten ASEAN countries and China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. FTAs are pacts between two or more nations to reduce barriers to imports and exports among them. They are “often signed by the developing countries in the hope of increasing their market access, improving their balance of trade (BOT), and reviving their economic growth by generating additional output and employment in their countries.”

The RCEP is the biggest regional trade agreement in the world.

The Philippine Senate last week ratified the RCEP, with only one negative vote coming from Sen. Risa Hontiveros, and one abstention, from Sen. Imee Marcos. The abstention is notable. She may have wanted to vote “no”, but that would be in direct defiance of her President-brother. Another example of a vote which is not for the national interest, but for a personal interest?

Let us now consider the Hontiveros “NO”. What was her reason? Because, she said, she had received letters from over a hundred organizations, including farmers groups (agriculture), trade unions (labor) and fair trade advocates, representing “millions of Filipinos that say that our country is not ready for this deal, we already obtain the benefits from our other agreements, and that we even stand to lose.” Understand, these letters must have been received by all the senators, but only Sen. Risa heeded the cries.

Do the arguments of these organizations hold any water? Let us see.

- “Our country is not ready for this deal.” — Well, India did not consider itself ready for this deal either, and withdrew from the RCEP in November 2019. Analysts opine that India was buying time to fix domestic problems (e.g. it needs to reform the low-productivity agricultural sector, improve education and innovation system, broaden tax base, reduce bureaucracy and red tape, etc.) before further opening up to trade. (“Why India is wise not to join RCEP”, Erken and Every, Rabobank Research). Does that sound familiar?

- “We already obtain the benefits from our other agreements.” — This argument is factually accurate. The ASEAN 10 already have a FTA among them, and the ASEAN has FTAs with China, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea, as well as India. That means that we already have benefits from these, and any other benefits from the RCEP will be marginal. RCEP, in fact, “began as a tidying up exercise, joining together in one overarching compact, the various trade agreements in place between ASEAN and the non-ASEAN countries above. This limits how much trade will be newly affected.” (The Economist, Nov. 2020)

China, Japan and South Korea, had been negotiating a trilateral FTA with each other since 2013 but without much progress. RCEP provides this to them.

- “We even stand to lose.” – A study in 2021 (Banga, Gallagher, Sharma, GEGI Working Paper, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University) did in fact state this categorically. “The results show that ASEAN will be a net loser in terms of its existing BOT post-RCEP since its BOT will deteriorate by six percent per annum. Imports into ASEAN will increase much more than its exports. Within ASEAN, BOT deteriorates for Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.” Philippine exports will actually decrease, post-RCEP.

Well then, who gains?

“BOT improves substantially for non-ASEAN countries like Japan and New Zealand…This will lead to decline in intra-ASEAN trade as ASEAN countries import from more efficient exporters like China instead of other ASEAN countries.”

The analysis also reveals that it is the developed countries which have been able to negotiate higher protection against imports as compared to ASEAN countries or even least developed countries within ASEAN.

Moreover, “ASEAN countries will also lose tariff revenues at a time when their industrial and trade growth have been adversely impacted due to the pandemic and domestic financial resources are needed for reviving their economies and repaying their debts.”

This unfortunately does not reconcile with the studies done by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), an institution I highly respect, and I think PIDS should explain why. For example, a 2021 PIDS study talks about an increase in exports as a result of RCEP, which directly contradicts the Banga, et. al., findings. They use different models, of course, but given the polar differences, we should be told which model conforms more to reality. By the way, one of the PIDS studies cites the Banga paper, and quotes from it extensively, but never reveals its negative findings. One has to wonder why.

In sum: all the paeans given to the RCEP – that it will accelerate post-pandemic economic recovery, that it will help bring more investments, that it will expand the country’s exports – is a cruel hoax on the Filipino people. If these will occur, it will occur only in the long-run, and after the government helps the different economic sectors be more competitive, and fixes its domestic problems. RCEP gives our country a little more market access to the other RCEP countries, but if we can’t compete, our products won’t sell in these markets.

In other words, if we don’t do our homework, we won’t pass. It’s that simple, Reader. – Rappler.com