AT A GLANCE

1. Poverty incidence decreased in 2018 but is expected to increase due to economic factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic

2. Self-rated hunger and self-rated poverty are the highest they have been since 2014, in part due to the pandemic but also because of the TRAIN law

3. SWS' self-rated hunger survey was conducted through mobile phone and computer assisted telephone interviews, which may have affected their poll results

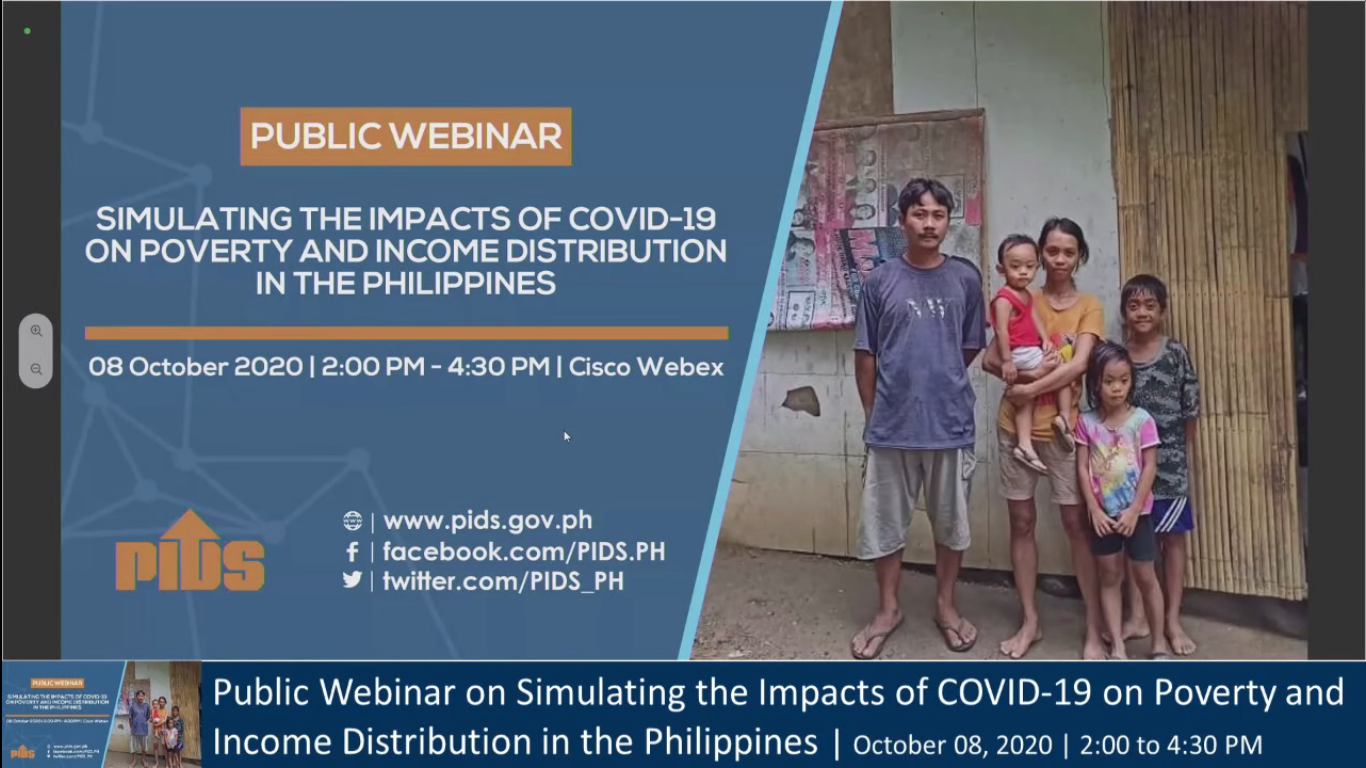

MANILA, Philippines – Poverty incidence declined in the first half of President Rodrigo Duterte’s term, but experts are expecting an inevitable increase in hunger and poverty because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The United Nation’s World Food Programme (WFP) predicts that 200 million people worldwide will lose access to basic food and nutrition in the coming months because of the pandemic. This is on top of the more than 800 million people who experienced food insecurity before the crisis.

Aside from its impact on healthcare systems, the WFP said in a June 2020 report that a combination of a global recession and dependence on volatile import, export, and credit markets will lead to unemployment and loss of income, and constrain countries’ abilities to respond to needs.

The most affected, they said, will be poor and marginalized populations and even groups that were able to meet their own needs previously.

The Philippines will not be exempt from the effects of the health crisis, despite the decrease in poverty incidence in recent years.

Poverty incidence, or the proportion of Filipino families with incomes not sufficient to buy their minimum basic food and non-food needs, was at an estimated 12.1% in 2018, according to data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). This is almost a 6 percentage point drop since the PSA’s last published full year poverty statistics in 2015, when poverty incidence was estimated to be 18%.

The PSA’s poverty data is published every 3 years. The chart below shows the trend in percentage of poverty incidence among Filipino families from 2003 to 2018. This does not include latest statistics.

Hunger on the rise

A more recent estimate of hunger and poverty are Social Weather Stations’s self-rated poverty and self-rated hunger surveys. These are conducted quarterly every year.

The effects of the pandemic can be clearly seen in SWS’ most recent hunger survey. According to their data, the percentage of Filipinos who were involuntarily hungry in May 2020 (16.7% or 4.2 million families) almost doubled since December 2019 (8.8% or around 2.1 million families). This is the highest the number has been since September 2014 (22.8% or 4.8 million families).

For Jose Ramon Albert, a research fellow at the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, these results are unsurprising. “[The increase in involuntary hunger was] clearly due to the pandemic, particularly the lockdown that sought to manage the virus, but reduced economic activity. Since at least a 3rd of the employed are in the informal sector, many of whom are likely dependent on day to day livelihood, you would expect hunger to rise,” he said in an email interview on Thursday, June 25.

As restrictions ease, he added, hunger is expected to ease as well, though not to the levels before the pandemic, as people are expected to lose jobs or continue to be affected by the crisis. There needs to be more targeted social protection by the government, he said, to manage the hunger levels.

For Leslie Lopez, assistant professor at Ateneo de Manila University’s Development Studies Program, it’s imperative that the marginalized are provided with food, money, and healthcare services, until they can get back on their feet.

“But it has to be clear that it is a stopgap mechanism for the meantime, it won’t be this way forever, because we don't also want to encourage mendicancy, wherein you’ll depend on the government for everything,” she said in a mix of English and Filipino during a phone interview on Monday, June 29.

“But given the situation that there aren't enough jobs to go around, there’s unemployment, and these people are the most vulnerable ones because they don't have savings to begin with… then in the meantime we can’t do nothing,” she said.

Increase in real, perceived poverty

When it comes to self-rated poverty, SWS’s most recent survey, conducted in December 2019, showed that 54% of respondents, or around 13.1 million families, considered themselves poor.

Like self-rated hunger in May 2020, this number is also the highest since September 2014.

When asked why Filipinos felt poorer even before the pandemic hit, Lopez said that based on her own research, it may be because of the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN) Act, which took effect in January 2018. The law reduced personal income taxes but increased taxes on cars, tobacco, sugar-sweetened beverages, and fuel.

In a study she was involved in, said Lopez, the families at a school in Metro Manila said they experienced more hunger in 2019 than in 2018 regardless of whether they were part of the school feeding program. This was attributed to having to live on the same income during the two years despite higher prices due to the TRAIN law.

According to the SWS survey, most respondents who rated themselves poor were in the Visayas (67%) followed by Mindanao (64%), Balance Luzon (47%), and Metro Manila (41%). There were increases in all of these areas compared to September.

Of the total 54% self-rated poor families, 7% (1.6 million) were not poor 1 to 4 years ago and another 7% (1.8 million) were not poor 5 or more years ago. The remaining 40% (9.7 million) have never experienced being non-poor.

“I will not be surprised if there will even be a higher spike in the coming months,” Lopez predicted. “Because if you're going to connect [the December 2019 spike] with the economic recession brought about by this pandemic, there are going to be more people who will be actually hungry or will perceive themselves as more hungry now, simply because they don't have enough money to buy the food that they want, regardless of whether it's nutritious or not.”

Survey limitations due to COVID-19

The SWS hunger survey for May 2020 was conducted through mobile phone and computer-assisted telephone interviewing because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting Luzon lockdown. They surveyed 4,010 Filipinos who were 15 years old and above: 294 in the National Capital Region, 1,645 in balance Luzon, 792 in the Visayas, and 1,279 in Mindanao.

According to their survey, 99% of the respondents received help in the form of food since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. Most people received food-help from the government (99%), followed by relatives (22%), private groups or institutions (16%), and friends (10%).

As of Wednesday, July 1, the December 2019 survey is the latest among SWS’s poverty polls. It was conducted using face-to-face interviews of 1,200 adults nationwide, with 300 each in Metro Manila, Balance Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao.

According to SWS, the results and analysis of their mobile survey will be released progressively, and they started with the hunger situation.

Both Albert and Lopez said the mobile surveys may affect the results.

If internet penetration rates were equal to the number of people with mobile phones and that number represents the entire population, Albert said, then the survey results would be alright. “But it is possible that the digital divide would put a bias to the survey results,” he said.

Lopez said that the way the survey was conducted adds another layer to how respondents may answer. “[The responses] can either go negative – that they would actually be more reserved in answering – or they will be more open. It can go both ways,” she said.

She also pointed out that there may be a systematic bias in the results, because those who use pre-paid phone lines, who might be of lower socioeconomic status, may have been excluded from the sampling frame. If this was the case, she said in a follow-up email, the hunger situation may actually be bleaker than what the survey results show.

1. Poverty incidence decreased in 2018 but is expected to increase due to economic factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic

2. Self-rated hunger and self-rated poverty are the highest they have been since 2014, in part due to the pandemic but also because of the TRAIN law

3. SWS' self-rated hunger survey was conducted through mobile phone and computer assisted telephone interviews, which may have affected their poll results

MANILA, Philippines – Poverty incidence declined in the first half of President Rodrigo Duterte’s term, but experts are expecting an inevitable increase in hunger and poverty because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The United Nation’s World Food Programme (WFP) predicts that 200 million people worldwide will lose access to basic food and nutrition in the coming months because of the pandemic. This is on top of the more than 800 million people who experienced food insecurity before the crisis.

Aside from its impact on healthcare systems, the WFP said in a June 2020 report that a combination of a global recession and dependence on volatile import, export, and credit markets will lead to unemployment and loss of income, and constrain countries’ abilities to respond to needs.

The most affected, they said, will be poor and marginalized populations and even groups that were able to meet their own needs previously.

The Philippines will not be exempt from the effects of the health crisis, despite the decrease in poverty incidence in recent years.

Poverty incidence, or the proportion of Filipino families with incomes not sufficient to buy their minimum basic food and non-food needs, was at an estimated 12.1% in 2018, according to data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). This is almost a 6 percentage point drop since the PSA’s last published full year poverty statistics in 2015, when poverty incidence was estimated to be 18%.

The PSA’s poverty data is published every 3 years. The chart below shows the trend in percentage of poverty incidence among Filipino families from 2003 to 2018. This does not include latest statistics.

Hunger on the rise

A more recent estimate of hunger and poverty are Social Weather Stations’s self-rated poverty and self-rated hunger surveys. These are conducted quarterly every year.

The effects of the pandemic can be clearly seen in SWS’ most recent hunger survey. According to their data, the percentage of Filipinos who were involuntarily hungry in May 2020 (16.7% or 4.2 million families) almost doubled since December 2019 (8.8% or around 2.1 million families). This is the highest the number has been since September 2014 (22.8% or 4.8 million families).

For Jose Ramon Albert, a research fellow at the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, these results are unsurprising. “[The increase in involuntary hunger was] clearly due to the pandemic, particularly the lockdown that sought to manage the virus, but reduced economic activity. Since at least a 3rd of the employed are in the informal sector, many of whom are likely dependent on day to day livelihood, you would expect hunger to rise,” he said in an email interview on Thursday, June 25.

As restrictions ease, he added, hunger is expected to ease as well, though not to the levels before the pandemic, as people are expected to lose jobs or continue to be affected by the crisis. There needs to be more targeted social protection by the government, he said, to manage the hunger levels.

For Leslie Lopez, assistant professor at Ateneo de Manila University’s Development Studies Program, it’s imperative that the marginalized are provided with food, money, and healthcare services, until they can get back on their feet.

“But it has to be clear that it is a stopgap mechanism for the meantime, it won’t be this way forever, because we don't also want to encourage mendicancy, wherein you’ll depend on the government for everything,” she said in a mix of English and Filipino during a phone interview on Monday, June 29.

“But given the situation that there aren't enough jobs to go around, there’s unemployment, and these people are the most vulnerable ones because they don't have savings to begin with… then in the meantime we can’t do nothing,” she said.

Increase in real, perceived poverty

When it comes to self-rated poverty, SWS’s most recent survey, conducted in December 2019, showed that 54% of respondents, or around 13.1 million families, considered themselves poor.

Like self-rated hunger in May 2020, this number is also the highest since September 2014.

When asked why Filipinos felt poorer even before the pandemic hit, Lopez said that based on her own research, it may be because of the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN) Act, which took effect in January 2018. The law reduced personal income taxes but increased taxes on cars, tobacco, sugar-sweetened beverages, and fuel.

In a study she was involved in, said Lopez, the families at a school in Metro Manila said they experienced more hunger in 2019 than in 2018 regardless of whether they were part of the school feeding program. This was attributed to having to live on the same income during the two years despite higher prices due to the TRAIN law.

According to the SWS survey, most respondents who rated themselves poor were in the Visayas (67%) followed by Mindanao (64%), Balance Luzon (47%), and Metro Manila (41%). There were increases in all of these areas compared to September.

Of the total 54% self-rated poor families, 7% (1.6 million) were not poor 1 to 4 years ago and another 7% (1.8 million) were not poor 5 or more years ago. The remaining 40% (9.7 million) have never experienced being non-poor.

“I will not be surprised if there will even be a higher spike in the coming months,” Lopez predicted. “Because if you're going to connect [the December 2019 spike] with the economic recession brought about by this pandemic, there are going to be more people who will be actually hungry or will perceive themselves as more hungry now, simply because they don't have enough money to buy the food that they want, regardless of whether it's nutritious or not.”

Survey limitations due to COVID-19

The SWS hunger survey for May 2020 was conducted through mobile phone and computer-assisted telephone interviewing because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting Luzon lockdown. They surveyed 4,010 Filipinos who were 15 years old and above: 294 in the National Capital Region, 1,645 in balance Luzon, 792 in the Visayas, and 1,279 in Mindanao.

According to their survey, 99% of the respondents received help in the form of food since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. Most people received food-help from the government (99%), followed by relatives (22%), private groups or institutions (16%), and friends (10%).

As of Wednesday, July 1, the December 2019 survey is the latest among SWS’s poverty polls. It was conducted using face-to-face interviews of 1,200 adults nationwide, with 300 each in Metro Manila, Balance Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao.

According to SWS, the results and analysis of their mobile survey will be released progressively, and they started with the hunger situation.

Both Albert and Lopez said the mobile surveys may affect the results.

If internet penetration rates were equal to the number of people with mobile phones and that number represents the entire population, Albert said, then the survey results would be alright. “But it is possible that the digital divide would put a bias to the survey results,” he said.

Lopez said that the way the survey was conducted adds another layer to how respondents may answer. “[The responses] can either go negative – that they would actually be more reserved in answering – or they will be more open. It can go both ways,” she said.

She also pointed out that there may be a systematic bias in the results, because those who use pre-paid phone lines, who might be of lower socioeconomic status, may have been excluded from the sampling frame. If this was the case, she said in a follow-up email, the hunger situation may actually be bleaker than what the survey results show.