Chief Mate William Gaspay’s commercial ship and his nine-month contract dock annually. But his three-year-old venture, WilNor Seaweed Farm, hasn’t docked yet.

Why should it? The 59-year-old Gaspay is in the middle of expanding his seaweed farm in Masinloc town, Zambales. He assured, though, that it won’t reach an area near the West Philippine Sea.

He established his seaweed farm using a P50,000 prize he won in a government-sponsored business-plan competition for seafarers two years ago. Of course, some of Gaspay’s savings were also used as start-up capital. His 1-hectare farm near the shore of Barangay Bamban in Masinloc eventually expanded to some 4 hectares.

Fueling the Gaspay family’s agri-enterprise venture is a migrant worker-breadwinner’s hope that the next phase of his life will be spent harvesting seaweeds and realizing his economic dreams from the sea.

The chief mate’s leap of faith into seaweed farming is also something migrant-sending Philippines is grappling with: How can billions of dollar remittances from compatriots in more than 200 countries and territories multiply into investments and businesses in their homeland? Are opportunities now ripe for overseas Filipino entrepreneurs after their homeland notched nearly 10 years of steady economic growth?

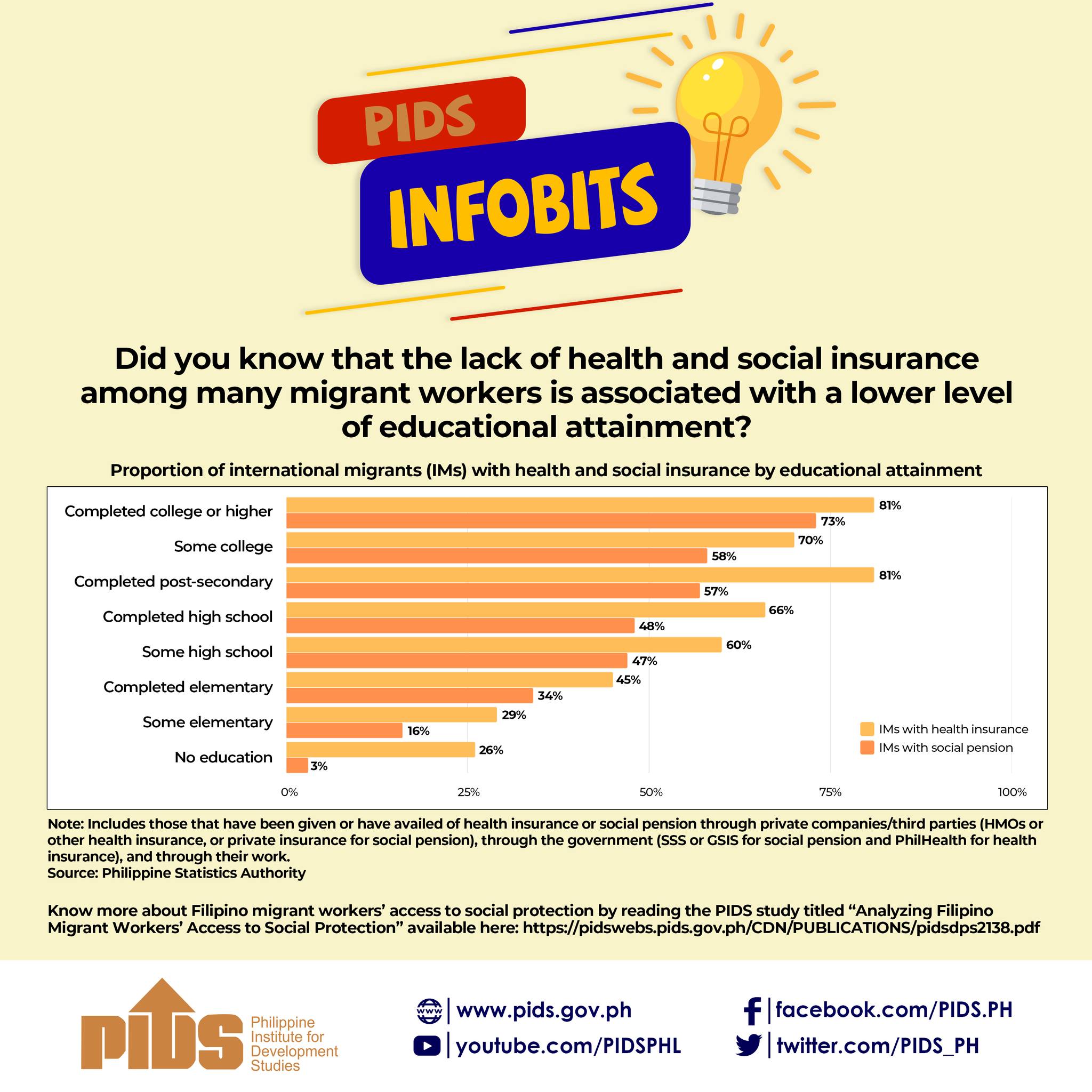

Since the turn of the new millennium until 2016, the Philippines’s formal financial system had received $194.183 billion in remittances from overseas Filipinos. The Philippines was among those leading recipient-countries of remittances, behind India, China and Mexico. When globally remittances became a policy discussion worldwide in 2000, Philippine policy-makers, migrant civil-society advocates and businesspeople had been thinking of ways to get a slice of migrants’ remittances.

But as migrant civil-society advocates had been saying in recent years, the homeland’s economic and investment environments must be “so conducive” if remittances were to channeled to “productive uses” (entrepreneurship, savings, some property acquisition and other forms of investment).

There’s more to the investment environment, though: Earmarking overseas remittance incomes for investment is a behavioral response. But quarterly survey findings of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’s (BSP) Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) since 2007 had not seen a significant allocation of remittance uses by overseas Filipino households for “investments”.

Out of the 10 uses of remittances (including savings), incomes for “investment” is ranked either eighth or ninth. The 11.2 percent of migrant households allotting remittances for investment, according to the CES in the fourth quarter of 2013, is the highest in 10 years.

Some migration analysts argued that turning as many current and returning overseas Filipinos (both migrant workers and permanent settlers abroad) into entrepreneurs is “problematic”. Not all of them are cut out for entrepreneurship, they contend.

But continued stay abroad, especially for Filipino migrants and returnees still within the working-age population, is a risk-mitigation measure while venturing into entrepreneurship at home. “They [migrant entrepreneurs] will have a hard time sustaining the income levels they had abroad upon their return,” economist Dr. Alvin Ang of Ateneo de Manila University said during a policy forum on migrant reintegration.

“Understand that when they return, ‘I need a regular income flow,’” Ang added. “That is something not easy for the government to handle.”

Most of the migrant-run enterprises anecdotally recorded by migration researchers and civil-society groups in various communities nationwide are in retail trade and services, and are micro-enterprises (the latter as part of the country’s nearly a million microenterprises). Migrant-entrepreneurship advocate Maria Angela Villalba of the Unlad Kabayan Migrant Services Foundation wishes that migrants’ enterprises would be “scalable business operations where government agencies play bigger roles” in enterprise development.

But before reaching those dreams, aspiring migrant entrepreneurship requires ample start-up capital. A 2014 study of migrant entrepreneurs in Carmona, Cavite and Mabini, Batangas found that the average start-up capital is P127,000 ($2,490.20), an amount that may take years for migrant workers who are in less-skilled occupations abroad to save.

Also, economist Dr. Celia Reyes and her research team found that the entrepreneurs in Carmona and Mabini are “usually small” in asset size and number of employees. “Their impact on their respective communities in terms of local development is limited,” Reyes and her team wrote in their Asian Development Bank-commissioned study.

That community-level finding may have eluded the popular policy statements of the current and former president, Rodrigo R. Duterte and Benigno S. Aquino III. Both presidents, speaking before Filipinos in some of their overseas trips, said the Philippines will be economically better so that overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) will “come home” and make migrating abroad “an option” than a necessity.

From the administration of former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo to this day, national development plans had mapped out measures to maximize overseas Filipino compatriots’ investible resources. These include financial-literacy programs and economic reintegration services for returning OFWs, led by the National Reintegration Center on OFWs.

Economic-assistance initiatives for distressed returning OFWs by the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) had endured, so are similar programs by nonmigration government agencies like the departments of Trade and Industry, Agriculture, Science and Technology and Social Welfare and Development. Local government units, in the past 15 years, are now being prodded by multilateral agencies and migrant civil-society organizations to include overseas migrants in local development plans.

Making overseas Filipinos and their households open at least basic savings accounts—included in the mainstream financial system—is among the targets of the BSP’s financial-inclusion strategy. That way, aspiring migrant entrepreneurs can access credit, as well as business-development services from banks, cooperatives and microfinance institutions.

These initiatives continue while the remittance flows of Filipino migrants have been slowing down since the 2008 global financial and economic crisis. Regardless, scaled-up migrant-run enterprises come few and far between. Some ring a bell, like the country’s fastest-growing spa and massage parlor, Nuat Thai, run by former Thailand migrant worker Kenneth Carredo. The Cebu City-originated enterprise expanded nationwide through franchising and now has over 100 branches.

If the Philippines wants to improve on its 6 percent to 7 percent annual GDP, or reach upper middle-income country status, there may be a need—for all Filipinos, not just those based abroad—to do “patriotic investing”, Ang said.

This entrepreneurship-driven economic dream that spills over to nonmigrants and benefits overseas remittance owners “will require those who have the capital to put these into productive and job-creating pursuits in lagging and left-behind sectors”, he added.

What Gaspay did can be considered patriotic investing. He is approaching seniorhood but he’s “young” in an industry that raked in $3.4 million in domestic revenues and $200 million in overseas profits in 2015, according to the Seaweed Industry Association of the Philippines.

He’s not settling for the 200,000 kilograms of seaweed he harvested in just two months. Gaspay made his farming area bigger by at least 3 hectares. WilNor even organized a community of seaweeds farmers in Barangay Bamban and linked the group to his growing venture.

WilNor’s Novaliches, Quezon City, office is quietly on the prowl looking for more markets for seaweeds harvests. And when William is at sea, his wife Norma, and son Leyzam tend to the business.

I am almost finished seafaring, Gaspay said. “But I am not yet done seaweed farming.”

Why should it? The 59-year-old Gaspay is in the middle of expanding his seaweed farm in Masinloc town, Zambales. He assured, though, that it won’t reach an area near the West Philippine Sea.

He established his seaweed farm using a P50,000 prize he won in a government-sponsored business-plan competition for seafarers two years ago. Of course, some of Gaspay’s savings were also used as start-up capital. His 1-hectare farm near the shore of Barangay Bamban in Masinloc eventually expanded to some 4 hectares.

Fueling the Gaspay family’s agri-enterprise venture is a migrant worker-breadwinner’s hope that the next phase of his life will be spent harvesting seaweeds and realizing his economic dreams from the sea.

The chief mate’s leap of faith into seaweed farming is also something migrant-sending Philippines is grappling with: How can billions of dollar remittances from compatriots in more than 200 countries and territories multiply into investments and businesses in their homeland? Are opportunities now ripe for overseas Filipino entrepreneurs after their homeland notched nearly 10 years of steady economic growth?

Since the turn of the new millennium until 2016, the Philippines’s formal financial system had received $194.183 billion in remittances from overseas Filipinos. The Philippines was among those leading recipient-countries of remittances, behind India, China and Mexico. When globally remittances became a policy discussion worldwide in 2000, Philippine policy-makers, migrant civil-society advocates and businesspeople had been thinking of ways to get a slice of migrants’ remittances.

But as migrant civil-society advocates had been saying in recent years, the homeland’s economic and investment environments must be “so conducive” if remittances were to channeled to “productive uses” (entrepreneurship, savings, some property acquisition and other forms of investment).

There’s more to the investment environment, though: Earmarking overseas remittance incomes for investment is a behavioral response. But quarterly survey findings of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’s (BSP) Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) since 2007 had not seen a significant allocation of remittance uses by overseas Filipino households for “investments”.

Out of the 10 uses of remittances (including savings), incomes for “investment” is ranked either eighth or ninth. The 11.2 percent of migrant households allotting remittances for investment, according to the CES in the fourth quarter of 2013, is the highest in 10 years.

Some migration analysts argued that turning as many current and returning overseas Filipinos (both migrant workers and permanent settlers abroad) into entrepreneurs is “problematic”. Not all of them are cut out for entrepreneurship, they contend.

But continued stay abroad, especially for Filipino migrants and returnees still within the working-age population, is a risk-mitigation measure while venturing into entrepreneurship at home. “They [migrant entrepreneurs] will have a hard time sustaining the income levels they had abroad upon their return,” economist Dr. Alvin Ang of Ateneo de Manila University said during a policy forum on migrant reintegration.

“Understand that when they return, ‘I need a regular income flow,’” Ang added. “That is something not easy for the government to handle.”

Most of the migrant-run enterprises anecdotally recorded by migration researchers and civil-society groups in various communities nationwide are in retail trade and services, and are micro-enterprises (the latter as part of the country’s nearly a million microenterprises). Migrant-entrepreneurship advocate Maria Angela Villalba of the Unlad Kabayan Migrant Services Foundation wishes that migrants’ enterprises would be “scalable business operations where government agencies play bigger roles” in enterprise development.

But before reaching those dreams, aspiring migrant entrepreneurship requires ample start-up capital. A 2014 study of migrant entrepreneurs in Carmona, Cavite and Mabini, Batangas found that the average start-up capital is P127,000 ($2,490.20), an amount that may take years for migrant workers who are in less-skilled occupations abroad to save.

Also, economist Dr. Celia Reyes and her research team found that the entrepreneurs in Carmona and Mabini are “usually small” in asset size and number of employees. “Their impact on their respective communities in terms of local development is limited,” Reyes and her team wrote in their Asian Development Bank-commissioned study.

That community-level finding may have eluded the popular policy statements of the current and former president, Rodrigo R. Duterte and Benigno S. Aquino III. Both presidents, speaking before Filipinos in some of their overseas trips, said the Philippines will be economically better so that overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) will “come home” and make migrating abroad “an option” than a necessity.

From the administration of former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo to this day, national development plans had mapped out measures to maximize overseas Filipino compatriots’ investible resources. These include financial-literacy programs and economic reintegration services for returning OFWs, led by the National Reintegration Center on OFWs.

Economic-assistance initiatives for distressed returning OFWs by the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) had endured, so are similar programs by nonmigration government agencies like the departments of Trade and Industry, Agriculture, Science and Technology and Social Welfare and Development. Local government units, in the past 15 years, are now being prodded by multilateral agencies and migrant civil-society organizations to include overseas migrants in local development plans.

Making overseas Filipinos and their households open at least basic savings accounts—included in the mainstream financial system—is among the targets of the BSP’s financial-inclusion strategy. That way, aspiring migrant entrepreneurs can access credit, as well as business-development services from banks, cooperatives and microfinance institutions.

These initiatives continue while the remittance flows of Filipino migrants have been slowing down since the 2008 global financial and economic crisis. Regardless, scaled-up migrant-run enterprises come few and far between. Some ring a bell, like the country’s fastest-growing spa and massage parlor, Nuat Thai, run by former Thailand migrant worker Kenneth Carredo. The Cebu City-originated enterprise expanded nationwide through franchising and now has over 100 branches.

If the Philippines wants to improve on its 6 percent to 7 percent annual GDP, or reach upper middle-income country status, there may be a need—for all Filipinos, not just those based abroad—to do “patriotic investing”, Ang said.

This entrepreneurship-driven economic dream that spills over to nonmigrants and benefits overseas remittance owners “will require those who have the capital to put these into productive and job-creating pursuits in lagging and left-behind sectors”, he added.

What Gaspay did can be considered patriotic investing. He is approaching seniorhood but he’s “young” in an industry that raked in $3.4 million in domestic revenues and $200 million in overseas profits in 2015, according to the Seaweed Industry Association of the Philippines.

He’s not settling for the 200,000 kilograms of seaweed he harvested in just two months. Gaspay made his farming area bigger by at least 3 hectares. WilNor even organized a community of seaweeds farmers in Barangay Bamban and linked the group to his growing venture.

WilNor’s Novaliches, Quezon City, office is quietly on the prowl looking for more markets for seaweeds harvests. And when William is at sea, his wife Norma, and son Leyzam tend to the business.

I am almost finished seafaring, Gaspay said. “But I am not yet done seaweed farming.”