The Philippines faces an economic and social crisis as a result of developments in the global economic scene. This will be precipitated by 1) China’s economic decline, 2) continuing economic troubles in Europe, the United States, and the newly emerging economies, 3) Japan’s recession, and 4) the decline in global oil prices.

China’s problems stem from overcapacity and overproduction. A property bubble has burst, “leaving roads leading to nowhere and ghost cities in its wake.” A credit-driven atmosphere has prevailed as available new credit ballooned —“exceeding by one-and-half times the size of the whole US commercial banking sector.” With bank deposits pegged at zero interest returns and property investments no longer viable, excess capital fled to an overvalued stock market. Oversubscription led to the Shanghai composite index plunging 43 percent in a two-month period in late 2015. In early January 2016, it “collapsed twice within a space of two weeks—followed by a run on its currency.” The renminbi’s fall prompted the People’s Bank of China to shell out $108 billion of foreign exchange reserves to stem the decline. A continued weakening of China’s currency could cause massive capital flight from the country’s economy.

China’s prominent role in the global economy—“17 percent of world GDP but one-third of global growth in the past 10 years”— caused global markets to tumble as well. About $3.2 trillion were wiped off the value of global stocks. The World Bank calculates that each 1 percent decline in China’s growth will cut growth rates in other Asian economies by 0.8 percent. Financial speculator George Soros warned that “the slowdown in China meant that the global economy was back once again to the crisis of 2008.” Citigroup says there is a 65-percent chance that China will lead the global economy into recession in 2016.

Elsewhere, the global capitalist system is showing signs of serious disorder. “Russia, Brazil and South Africa are in deep recession, and the Eurozone grew by a miserable 1.6 percent in 2015.” Debt problems in 2015 appear unprecedented. In the United States, federal debt is 74 percent of GDP; in China, it is estimated to be more than 240 percent, and in Japan, it hit 246 percent.

In the United States, industrial production declined by 1.8 percent year on year in December 2015, estimated real GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2015 slowed to 0.7 percent, and the stock market wiped $1.4 trillion from the value of the top 500 firms in the first 10 trading days of January. The growing strength of the US dollar also adds to the fears of a 2016 recession.

In November 2015, the Japanese economy entered its fourth recession in five years with the economy shrinking by 0.8 percent in July-September 2015 on top of the 0.7 percent contraction in April-June 2015. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe instituted monetary and fiscal stimulus programs to motivate investors, but “Abenomics” is faltering.

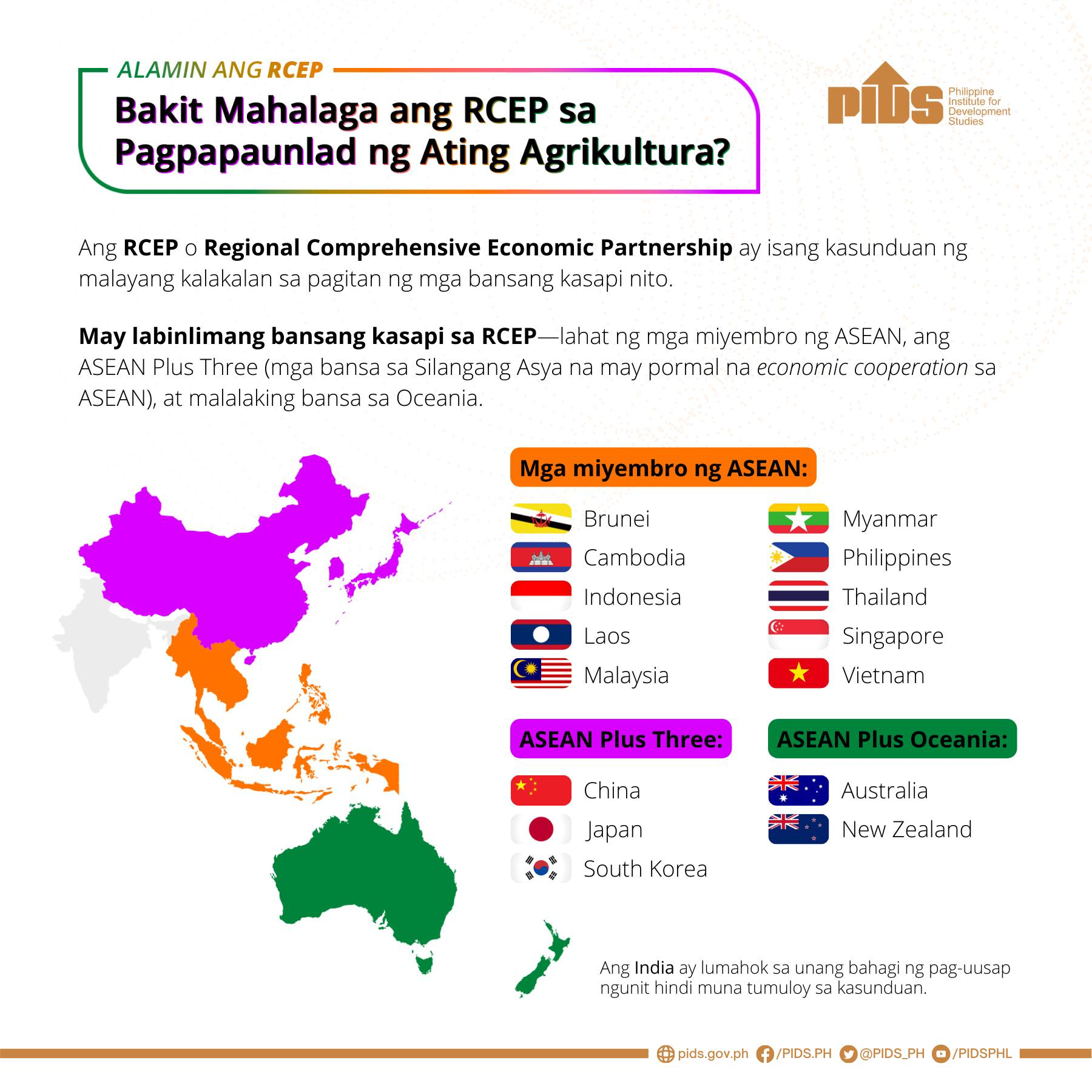

The Philippines is highly dependent on economic relations with Japan and China. In 2014 Japan was its top trading partner, with 15 percent of its total trade, and China was its second largest trading partner, with 14.3 percent of its total trade.

Philippine exports to China in December 2015 hit $746.82 million, up year on year by 79 percent. With that, China emerged as the third-biggest export market for Philippine-made goods next to Japan. Goods imported by the Philippines from China reached $671.12 million in November, up year on year by 14.6 percent. China remains the Philippines’ biggest source of imports during the month. Japan continues to be the Philippines’ top bilateral donor, and China extended $1.27 billion in official development assistance funds to the Philippines from 2002 to 2010.

The oil industry is in its deepest downturn since the 1990s. In the third week of January, oil prices fell to a 12-year low of $27.10 per barrel. Oil earnings are down for companies; two-thirds of rigs have been decommissioned; investments in exploration and production have been sharply cut; an estimated 250,000 workers have lost their jobs; and manufacture of drilling and production equipment has fallen sharply.

On the supply side, the main cause is overproduction, especially with the recent lifting of Western sanctions on Iran. On the demand side, the price fall can be traced to weak demand by the suffering economies of Europe and developing countries.

The major losers are the oil-producing countries, especially less developed ones like Venezuela, Nigeria, Ecuador and Brazil. Traditional oil giants like Saudi Arabia and Gulf allies will see their oil revenues fall by $300 billion in 2016. Major oil companies have cut payrolls, others have slashed dividends, and 40 companies in North America have declared bankruptcy. The US shale oil industry, which had contributed to the overproduction due to new finds, is groaning from an accumulated $200 billion in debts.

For the Philippines, the severe constriction of its exports will be inevitable. In fact, this has actually already begun. For 2015, the National Economic and Development Authority reported a lackluster export growth of 5.5 percent, compared to 11.3 percent in 2014. Gilbert Llanto, head of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, believes that “trade-led growth may not be a viable option for the Philippines in the immediate future.” Lastly, the oil price fall could see 1.5 million Filipino workers in the Middle East losing their jobs and returning home with no work awaiting them.

Is the Philippines ready for an impending global economic downturn?//

Eduardo C. Tadem is president of the Freedom from Debt Coalition and professorial lecturer in Asian studies, University of the Philippines Diliman. He holds a PhD in Southeast Asian studies from the National University of Singapore.

China’s problems stem from overcapacity and overproduction. A property bubble has burst, “leaving roads leading to nowhere and ghost cities in its wake.” A credit-driven atmosphere has prevailed as available new credit ballooned —“exceeding by one-and-half times the size of the whole US commercial banking sector.” With bank deposits pegged at zero interest returns and property investments no longer viable, excess capital fled to an overvalued stock market. Oversubscription led to the Shanghai composite index plunging 43 percent in a two-month period in late 2015. In early January 2016, it “collapsed twice within a space of two weeks—followed by a run on its currency.” The renminbi’s fall prompted the People’s Bank of China to shell out $108 billion of foreign exchange reserves to stem the decline. A continued weakening of China’s currency could cause massive capital flight from the country’s economy.

China’s prominent role in the global economy—“17 percent of world GDP but one-third of global growth in the past 10 years”— caused global markets to tumble as well. About $3.2 trillion were wiped off the value of global stocks. The World Bank calculates that each 1 percent decline in China’s growth will cut growth rates in other Asian economies by 0.8 percent. Financial speculator George Soros warned that “the slowdown in China meant that the global economy was back once again to the crisis of 2008.” Citigroup says there is a 65-percent chance that China will lead the global economy into recession in 2016.

Elsewhere, the global capitalist system is showing signs of serious disorder. “Russia, Brazil and South Africa are in deep recession, and the Eurozone grew by a miserable 1.6 percent in 2015.” Debt problems in 2015 appear unprecedented. In the United States, federal debt is 74 percent of GDP; in China, it is estimated to be more than 240 percent, and in Japan, it hit 246 percent.

In the United States, industrial production declined by 1.8 percent year on year in December 2015, estimated real GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2015 slowed to 0.7 percent, and the stock market wiped $1.4 trillion from the value of the top 500 firms in the first 10 trading days of January. The growing strength of the US dollar also adds to the fears of a 2016 recession.

In November 2015, the Japanese economy entered its fourth recession in five years with the economy shrinking by 0.8 percent in July-September 2015 on top of the 0.7 percent contraction in April-June 2015. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe instituted monetary and fiscal stimulus programs to motivate investors, but “Abenomics” is faltering.

The Philippines is highly dependent on economic relations with Japan and China. In 2014 Japan was its top trading partner, with 15 percent of its total trade, and China was its second largest trading partner, with 14.3 percent of its total trade.

Philippine exports to China in December 2015 hit $746.82 million, up year on year by 79 percent. With that, China emerged as the third-biggest export market for Philippine-made goods next to Japan. Goods imported by the Philippines from China reached $671.12 million in November, up year on year by 14.6 percent. China remains the Philippines’ biggest source of imports during the month. Japan continues to be the Philippines’ top bilateral donor, and China extended $1.27 billion in official development assistance funds to the Philippines from 2002 to 2010.

The oil industry is in its deepest downturn since the 1990s. In the third week of January, oil prices fell to a 12-year low of $27.10 per barrel. Oil earnings are down for companies; two-thirds of rigs have been decommissioned; investments in exploration and production have been sharply cut; an estimated 250,000 workers have lost their jobs; and manufacture of drilling and production equipment has fallen sharply.

On the supply side, the main cause is overproduction, especially with the recent lifting of Western sanctions on Iran. On the demand side, the price fall can be traced to weak demand by the suffering economies of Europe and developing countries.

The major losers are the oil-producing countries, especially less developed ones like Venezuela, Nigeria, Ecuador and Brazil. Traditional oil giants like Saudi Arabia and Gulf allies will see their oil revenues fall by $300 billion in 2016. Major oil companies have cut payrolls, others have slashed dividends, and 40 companies in North America have declared bankruptcy. The US shale oil industry, which had contributed to the overproduction due to new finds, is groaning from an accumulated $200 billion in debts.

For the Philippines, the severe constriction of its exports will be inevitable. In fact, this has actually already begun. For 2015, the National Economic and Development Authority reported a lackluster export growth of 5.5 percent, compared to 11.3 percent in 2014. Gilbert Llanto, head of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, believes that “trade-led growth may not be a viable option for the Philippines in the immediate future.” Lastly, the oil price fall could see 1.5 million Filipino workers in the Middle East losing their jobs and returning home with no work awaiting them.

Is the Philippines ready for an impending global economic downturn?//

Eduardo C. Tadem is president of the Freedom from Debt Coalition and professorial lecturer in Asian studies, University of the Philippines Diliman. He holds a PhD in Southeast Asian studies from the National University of Singapore.