Working at the, the government think tank, I have had the pleasure of collaborating with several fellows, management, associates, and research fellows either to write up reports on policy research, to advocate for development policy issues, or to provide legislators feedback on proposed legislation. Many of them are women economists and development researchers of esteemed caliber and work ethic: Celia Reyes, Rosario Manasan, Rafaelita Aldaba, Erlinda Medalla, Ramonette Serafica, Connie Dacuycuy, Sheila Siar, Maureen Anne Rosellon and Jana Flor Vizmanos.

As a statistician, I have had minimal training in economics: one undergrad and one graduate course. Much of development economics involves common-sense insights, though common sense can sometimes not be so common.

These days, there is some level of excitement globally for women in economics.

Several leading organizations in the development community have appointed women as their chief economists. In early October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) appointed its first female chief economist in Harvard professor Gita Gopinath. Earlier this year, the World Bank (WB) named Yale professor Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg as chief economist (the second female out of 14 WB chief economists since 1972), while Laurence Boone joined the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) also as chief economist.

Having women in these leadership roles in economics is encouraging, but such optimism must be tempered given the dearth of females in economics.

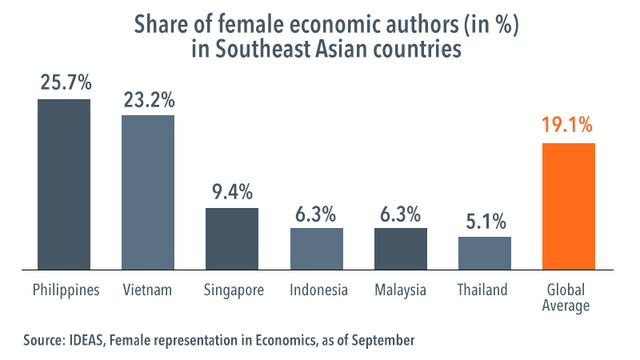

A based on the Research Papers in Economics database suggests that only a fifth (19%) of published economists are women. Among Southeast Asian member states, the Philippines and Vietnam posted slightly higher proportions at around a quarter, i.e., 25.7% and 23.2%, respectively.

Other ASEAN-member states registered lower share of women among published economists: Singapore, 9.4%; Thailand 5.1%; Indonesia 6.3%; and Malaysia 6.3%.

In August last year, former PIDS board member Romy Bernardo posted a photo on Facebook of a gathering of “presidents of the Philippine Economics Society (PES) through the years.” My immediate comment was “hmmm lacks gender balance.” Ciel Habito, former socioeconomic planning secretary and PIDS chairman of the board, responded that they also noted that PES has had only 3 women presidents since 1961.

I pointed out that we have done a much better job in the Philippine Statistical Association, Inc., at having 10 female and 22 male presidents, which is still below gender parity.

Reflection of gender gap in Philippine society?

Economics and statistics are not the only areas where men outnumber women in leadership.

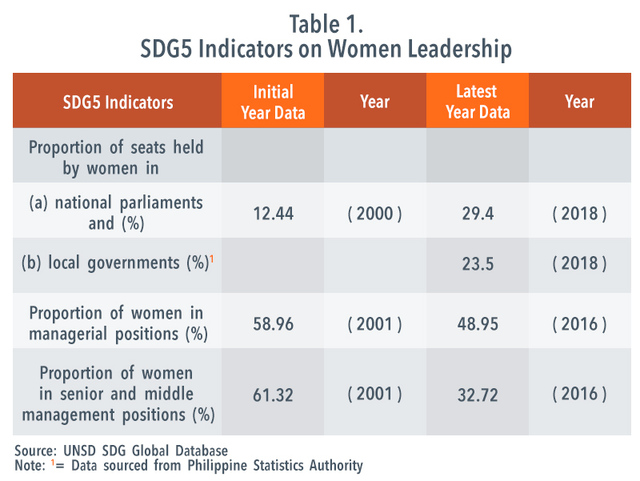

Last year, we released a study at PIDS that observed that there are too few women leaders across the Philippines in both the public and private sectors (see Table 1).

Women are underrepresented in the elected posts in Congress, and in appointed posts in the executive, and even the judiciary.

Cabinet secretaries have remained largely male-dominated from 1986 to the present, even during years when the Philippines was headed by a woman.

While many women have taken leadership in the health, tourism, and social welfare departments, there are far fewer in economics, budget and management, finance, and foreign affairs.

A few days ago, the President selected a retiring army chief to be first male ever to head the Department of Social Welfare and Development since 1986, seemingly breaking stereotypes, but gender stereotypes actually persist.

In the judiciary, only two women were named as Chief Justice in the entire history of the Supreme Court (with one of them quo warranto). The distribution of judges, by sex, has become more gender balanced over the last 15 years. As of 2015, the proportion of female judges stands at 43.8%, a big jump from 19.7% in 2000.

In the private sector, women’s representation in managerial positions in industry may seemingly be at parity, but actually, men still dominate in the highest positions, including chief-level positions, memberships in boards, and top management.

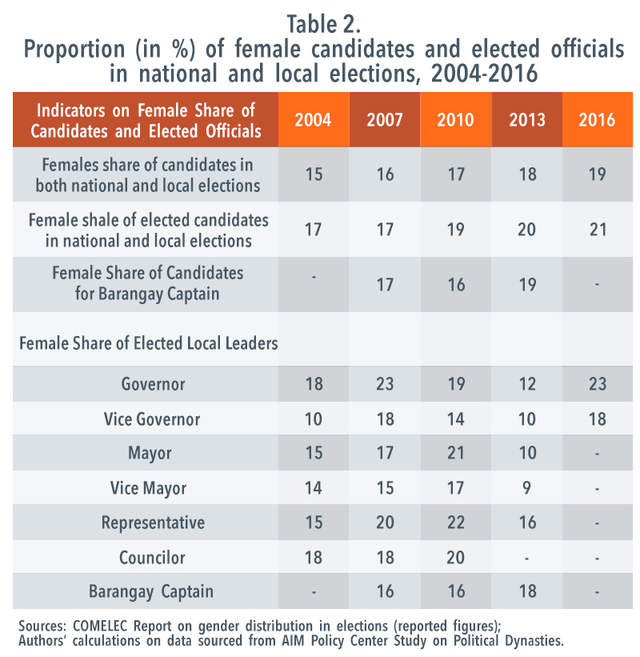

In the case of elective posts, the small female representation is due not to the low inclination of the general public to vote for women, but to the limited involvement of women in electoral politics (see Table 2).

Other StoriesBy reinforcing opportunities for higher-income women and extending them to poorer women, the Philippines could add $40 billion to its annual GDP in 2025

Filipinas are more equally represented in business and government than most of their neighbors in the Asia Pacific region, a Mastercard study shows

As regards economic opportunities in the country, there are too few women in the labor market: about half of the women are in the labor force, compared to three quarters of men.

While women who join the labor force seem to have similar economic opportunities as men since sex-disaggregated unemployment rates are not substantially different, data disaggregation of employment across major sectors shows that men and women are situated differently in the job market.

A third of working men are engaged in agriculture, over two-fifth in services, and a fifth in industry. Working women, on the other hand, are predominantly in the services sector with nearly 7 in 10 women working in this sector, while one in ten work in industry, and the remaining fifth work in agriculture.

The gender imbalance in the economics profession is worth addressing since the share of women’s voice among thinkers impacts upon how government view gender inequality in society.

Where female economists see unequal opportunity between males and females, their male counterparts see the result of diverging skill sets and choices. Female economists have also been found to be

more inclined than their male peers to favour government over market interventions.

Since governments listen to economists for policy advice and direction, the importance of gender balance in economics can translate to gender-responsive economic policies or, at the very least to a recognition that gender imbalance exists in the labor market.

Where are the women in economics?

Although some theories point to women finding other career paths more attractive, there are also indications of barriers for women to enter or pursue economics in recent research.

One study posits that women writing economics papers are held to higher standards than men.

Media representation of female economists could also be part of the issue. A 2015 New York Times article points to a tendency for the media to relegate female academic authors to co-author roles even when there are indications that the women are the lead researchers.

In Australia, more than 90% of economists or economic analysts quoted in news, business or finance sections in the country are men. Male dominance is also seen in the proportion of male CEOs featured in the media (86%) and of company chairs quoted (90%).

Bias extends to online and social media, with a based on the monitoring of an online forum for economic careers showing that while discussions of men focus on the professional sphere, discussions of women tend to be around personal or physical attributes.

These challenges show that addressing the gender imbalance in economics takes more than merely appointing women to top positions in the IMF, World Bank or OECD. Unless gender equality exists across all positions, having women at the helm spells fleeting success.

The American Economic Association calls this a leaky pipeline of women in economics, observing that in the academe, where many economists also sit as faculty members, the share of women declines as they move from being PhD graduates to full professors.

This is also likely in Southeast Asia, where the number of men and women tends to be balanced at entry but favor men closer to leadership roles.

In the Philippines, women do tend to get promoted to senior management but often fall short of making corporate executive or member of the board.

How can we plug these leaks? We need to eliminate barriers to women in economics from entry level to leadership roles. Interventions may include putting in place recruitment quotas, at least for some time period (say 5 to 10 years), to ensure that women enter the profession in the same ratio as men.

Encouraging organizations to put in place gender equality practices is also a step forward. Clearly outlined policies or practices in work environments help check against unconscious or hidden gender biases, which are pitfalls even among those who claim to be gender equality advocates.

In addition to plugging leaks, we also need to widen our pool of potential economists by encouraging young women and girls to join the discipline. Strong female role models help, with a study finding greater interest in economics among female students who are exposed to women in economics.

Encouraging research on gender equality

There is a growing body of knowledge around gender equality in the Philippines.

Some of these will be highlighted at the 56th Philippine Economic Society Annual Meeting and Conference on November 7, in a breakout session titled “Where are the women in the Philippines’ high-growth economy?”

The session is organized by Investing in Women, an initiative of the Australian Government that works across Indonesia, Myanmar, the Philippines and Vietnam to promote women’s economic empowerment.

Presenters in the session include Clarissa David of the University of the Philippines, who co-authored with me and my PIDS research assistant Jana Flor Vizmanos a study on factors affecting women’s participation in leadership.

Raymundo Addun of the Philippine National Anti-Poverty Commission will talk about gender discrimination in the workplace. Maribel Daño-Luna of the Asian Institute of Management will share a study on women-owned SMEs.

Exposure to such research might force us to introspect on our views on workplace gender equality and to recognise that there is gender imbalance within our ranks. We ought to accelerate change in public attitudes around these issues, work on electoral reforms, advocate for soft quotas and even soft quotas and affirmative action so that we can foster equal opportunities for men and women so that each has pathways to leadership that are not marred by gender-based barriers.

– Rappler.com