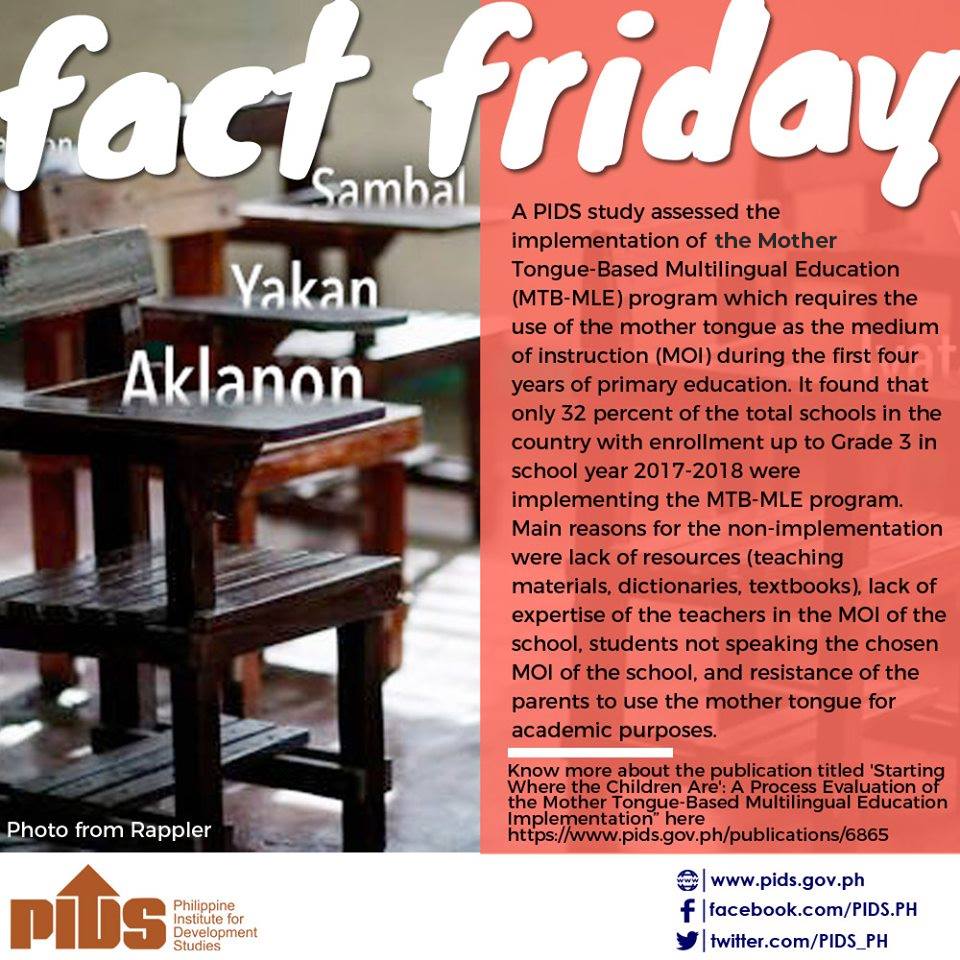

The implementation of the Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) program is being hampered by a number of challenges.

This was revealed by Jennifer Monje, co-author of the study “‘Starting Where the Children Are’: A Process Evaluation of the Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education Implementation”, which was presented at a public seminar recently organized by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies.

The Department of Education (DepEd) defines MTB-MLE as “the effective use of more than two languages for literacy and instruction”. In 2009, DepEd released Department Order No. 74 mandating the use of mother tongue as the medium of instruction during the first four years of primary education while students learn Filipino and English as subject areas.

The study looked at 18 randomly selected elementary schools from linguistically diverse and less linguistically diverse communities in Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. Key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and an online survey were also conducted. To assess the program implementation in the said schools, the study focused on program theory, service delivery and utilization, and program organization.

“The MTB-MLE is based on sound, pedagogical foundation, and embodies the concept of a learner-centered education,” Monje said. However, with the problems besetting the program, DepEd has to find more effective, efficient, and acceptable ways of implementing it, she stressed.

According to Monje, one of the common challenges faced by the MTB-MLE program in terms of program theory is the presence of many languages spoken in schools.

“The design of the MTB-MLE is that there is only one mother tongue to which the Filipino and English are added… Even when regions are deemed monolingual, like for example in the NCR, there were several schools with many languages because students come from all over the Philippines and they bring with them their languages,” Monje explained.

The study also found a lack of common understanding and wrong appreciation of the program among teachers, resulting in their dissatisfaction and unhappiness because of “additional workload”.

In terms of service delivery and utilization, Monje said that “all elements of the program had not been in place,” with problems such as lack of learning materials and competent teachers.

“We saw that there were many places where there weren’t any books that teachers could use. Sometimes, lessons were created on the fly or sometimes the teachers themselves would have to source out materials and use them for teaching kids.”

There is also the issue of teachers not speaking the language of the community. Moreover, the study also found that the program “appears to be limited to public schools” as the private schools have developed their own version of the program that only includes teaching the mother tongue as an additional subject.

“They [private schools] feel that by not using the mother tongue of the community, they have an edge over public schools because they still maintain English as the mother tongue of the students,” Monje said.

Further, procurement issues, especially the delivery of learning materials, mostly hamper the operation of the program. Some schools reported that they have yet to receive textbooks, despite the program being implemented as early as 2009. Additionally, Monje said that the “MTB-MLE-related activities had to compete for funding in the general budget [maintenance and other operating expenses] of the schools.”

To address issues on program logic and plausibility, the study stressed the importance of making teachers, as well as parents, understand the significance of shifting to a mother tongue-based multilingual education. They also called on the government to reassess the “one-mother-tongue-per-locality” policy. Monje noted that DepEd has already done this through language mapping.

Meanwhile, the study recommended continuous training for teachers, whether new hires or veterans, as well as the creation of quality-prepared, reviewed, and updated localized learning materials to address problems in service delivery and utilization. They also urged schools to “instill pride and value of languages” by making them visible in schools. Monje noted that some schools are already using their mother tongue in their posters.

Lastly, on the issue of program organization, Monje said schools should have a designated fund for MTB-MLE operation activities. She also urged schools to seek help from their local governments in terms of funding localization efforts for the program. ###

This was revealed by Jennifer Monje, co-author of the study “‘Starting Where the Children Are’: A Process Evaluation of the Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education Implementation”, which was presented at a public seminar recently organized by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies.

The Department of Education (DepEd) defines MTB-MLE as “the effective use of more than two languages for literacy and instruction”. In 2009, DepEd released Department Order No. 74 mandating the use of mother tongue as the medium of instruction during the first four years of primary education while students learn Filipino and English as subject areas.

The study looked at 18 randomly selected elementary schools from linguistically diverse and less linguistically diverse communities in Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. Key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and an online survey were also conducted. To assess the program implementation in the said schools, the study focused on program theory, service delivery and utilization, and program organization.

“The MTB-MLE is based on sound, pedagogical foundation, and embodies the concept of a learner-centered education,” Monje said. However, with the problems besetting the program, DepEd has to find more effective, efficient, and acceptable ways of implementing it, she stressed.

According to Monje, one of the common challenges faced by the MTB-MLE program in terms of program theory is the presence of many languages spoken in schools.

“The design of the MTB-MLE is that there is only one mother tongue to which the Filipino and English are added… Even when regions are deemed monolingual, like for example in the NCR, there were several schools with many languages because students come from all over the Philippines and they bring with them their languages,” Monje explained.

The study also found a lack of common understanding and wrong appreciation of the program among teachers, resulting in their dissatisfaction and unhappiness because of “additional workload”.

In terms of service delivery and utilization, Monje said that “all elements of the program had not been in place,” with problems such as lack of learning materials and competent teachers.

“We saw that there were many places where there weren’t any books that teachers could use. Sometimes, lessons were created on the fly or sometimes the teachers themselves would have to source out materials and use them for teaching kids.”

There is also the issue of teachers not speaking the language of the community. Moreover, the study also found that the program “appears to be limited to public schools” as the private schools have developed their own version of the program that only includes teaching the mother tongue as an additional subject.

“They [private schools] feel that by not using the mother tongue of the community, they have an edge over public schools because they still maintain English as the mother tongue of the students,” Monje said.

Further, procurement issues, especially the delivery of learning materials, mostly hamper the operation of the program. Some schools reported that they have yet to receive textbooks, despite the program being implemented as early as 2009. Additionally, Monje said that the “MTB-MLE-related activities had to compete for funding in the general budget [maintenance and other operating expenses] of the schools.”

To address issues on program logic and plausibility, the study stressed the importance of making teachers, as well as parents, understand the significance of shifting to a mother tongue-based multilingual education. They also called on the government to reassess the “one-mother-tongue-per-locality” policy. Monje noted that DepEd has already done this through language mapping.

Meanwhile, the study recommended continuous training for teachers, whether new hires or veterans, as well as the creation of quality-prepared, reviewed, and updated localized learning materials to address problems in service delivery and utilization. They also urged schools to “instill pride and value of languages” by making them visible in schools. Monje noted that some schools are already using their mother tongue in their posters.

Lastly, on the issue of program organization, Monje said schools should have a designated fund for MTB-MLE operation activities. She also urged schools to seek help from their local governments in terms of funding localization efforts for the program. ###