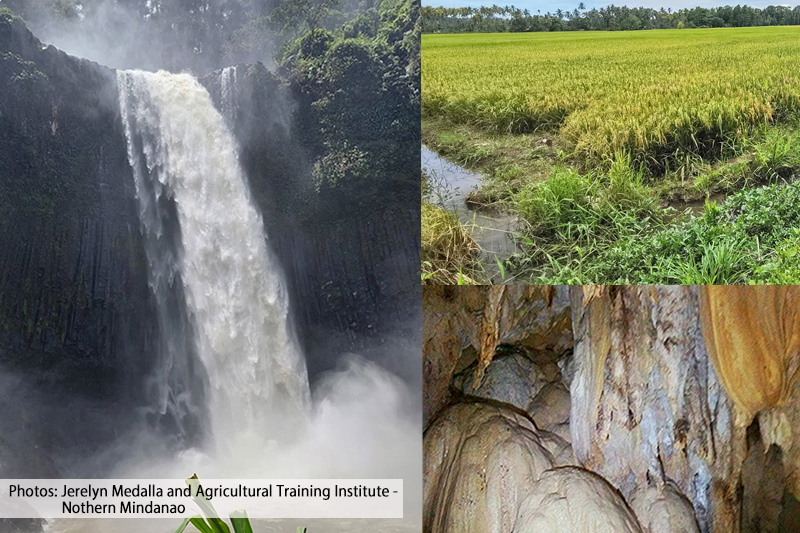

RICE HAS BEEN an indispensable staple food on the plates of the majority of Filipinos and is crucial in providing employment to millions of farmers. Rice policy adopts protectionism as an instrument for food security and livelihood promotion, limiting the intensity of competition from foreign suppliers of the staple.

A study by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) on the state of competition in the staple foods sector zeroes in on the current issues being confronted by the consumers and producers of rice. It examines the policy implications of the lack of competition between domestic and foreign producers in the country’s rice market. Findings show that the restraint in competition has been ultimately detrimental to consumers; opening up the rice trade, together with targeted producer support, will confer tremendous benefits to the rice-consuming public while helping farmers transition to a more competitive regime.

The National Food Authority (NFA) serves as the primary regulatory agency for the country’s main staple. Although the NFA seeks to promote food security and price stabilization, the outcome of its actions prove otherwise. These outcomes are directly attributed to its quantitative restrictions (QR) on rice importation, enforced by its statutory monopoly on rice importation.

The QR regime is uniquely applied for rice; due to the World Trade Organization Agreement, since 1995 the country has replaced QRs with tariffs for all other agricultural products -- a policy called “tariffication.” However, it applied for -- and obtained -- an exemption for rice. The exception is time-bound, ending initially in 2005, but extended by request of the Philippines to 2012, and again to 2017. The QR regime for rice has been programmed to support the goal of rice self-sufficiency, initially in 2013, now extended to 2016.

The exercise of the QR has elevated the domestic price above the world price of rice. Usually this has been accompanied with a stable domestic price of rice at the retail level, compared to the high volatility of the world price. There are some prominent exceptions, the price surge of 2013 being the most recent example. In this regard, the retail price of well-milled rice spiked to P32 in 2013 from P28 in the previous year. This amounts to an enormous 14% increase in the price of rice in just a year. Adding to this, 2013-2014 farmgate prices have also been relatively high, reaching a P20/kg level and above. This puts into question the competitiveness of the NFA procurement system and the viability of the existing import restrictions.

The price surge has been blamed on price manipulation by traders. However, this is mere scapegoating. The same study shows that the domestic marketing of rice is actually highly competitive. This is consistent with decades of studies of rice marketing, which have concluded likewise.

The real reason for the price increase is the shrinking import quota. The expectation is that domestic rice supply could expand sufficiently to meet domestic demand. Recent experience demonstrates that closing the supply-demand gap will require a higher domestic price -- an outcome detrimental to consumers, especially the poor and undernourished. Furthermore, interviews of key informants indicate that the little imports that are allowed, are cornered by a privileged few, who thereby make a killing out of the difference between domestic and world prices.

Protectionism in this case indisputably helps domestic producers, but harms consumers. An accepted method of comparing costs and benefits is economic surplus analysis, here implemented by a computer model of the rice market known as the Total Welfare Impact Simulator (TWIST).

TWIST is applied to the 2013 market in two alternative scenarios: first is free trade; second is increase in import quota back to 2011 levels. Opening up the sector through free trade will yield an economic benefit amounting to P138.5 billion. On the other hand, increasing the import quota would lead to about P25.2-billion increase in economic surplus.

Free trade is undeniably detrimental to farmers; the simulation shows that they will lose the equivalent of P34 billion. However the benefits to consumers is large, and net benefit to society is still large as mentioned above. Gradual reform can be implemented by converting the import quota into tariff protection, with a moderate level of tariff. This tarrification should be accompanied by producer support policies to avoid severe dislocation. Such policies are expected to strike a balance between the welfare of producers and those of consumers; in the end, the essence of food security is consistent access to affordable food.

Roehlano Briones and Lovely Ann Tolin are fellows from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies. This piece was adapted from CREW Diagnostic Country Report: Philippines, a study conducted by PIDS with financial and technical support from the Centre for Competition, Investment and Economic Regulation (CUTS-CIER), Jaipur, India. //

A study by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) on the state of competition in the staple foods sector zeroes in on the current issues being confronted by the consumers and producers of rice. It examines the policy implications of the lack of competition between domestic and foreign producers in the country’s rice market. Findings show that the restraint in competition has been ultimately detrimental to consumers; opening up the rice trade, together with targeted producer support, will confer tremendous benefits to the rice-consuming public while helping farmers transition to a more competitive regime.

The National Food Authority (NFA) serves as the primary regulatory agency for the country’s main staple. Although the NFA seeks to promote food security and price stabilization, the outcome of its actions prove otherwise. These outcomes are directly attributed to its quantitative restrictions (QR) on rice importation, enforced by its statutory monopoly on rice importation.

The QR regime is uniquely applied for rice; due to the World Trade Organization Agreement, since 1995 the country has replaced QRs with tariffs for all other agricultural products -- a policy called “tariffication.” However, it applied for -- and obtained -- an exemption for rice. The exception is time-bound, ending initially in 2005, but extended by request of the Philippines to 2012, and again to 2017. The QR regime for rice has been programmed to support the goal of rice self-sufficiency, initially in 2013, now extended to 2016.

The exercise of the QR has elevated the domestic price above the world price of rice. Usually this has been accompanied with a stable domestic price of rice at the retail level, compared to the high volatility of the world price. There are some prominent exceptions, the price surge of 2013 being the most recent example. In this regard, the retail price of well-milled rice spiked to P32 in 2013 from P28 in the previous year. This amounts to an enormous 14% increase in the price of rice in just a year. Adding to this, 2013-2014 farmgate prices have also been relatively high, reaching a P20/kg level and above. This puts into question the competitiveness of the NFA procurement system and the viability of the existing import restrictions.

The price surge has been blamed on price manipulation by traders. However, this is mere scapegoating. The same study shows that the domestic marketing of rice is actually highly competitive. This is consistent with decades of studies of rice marketing, which have concluded likewise.

The real reason for the price increase is the shrinking import quota. The expectation is that domestic rice supply could expand sufficiently to meet domestic demand. Recent experience demonstrates that closing the supply-demand gap will require a higher domestic price -- an outcome detrimental to consumers, especially the poor and undernourished. Furthermore, interviews of key informants indicate that the little imports that are allowed, are cornered by a privileged few, who thereby make a killing out of the difference between domestic and world prices.

Protectionism in this case indisputably helps domestic producers, but harms consumers. An accepted method of comparing costs and benefits is economic surplus analysis, here implemented by a computer model of the rice market known as the Total Welfare Impact Simulator (TWIST).

TWIST is applied to the 2013 market in two alternative scenarios: first is free trade; second is increase in import quota back to 2011 levels. Opening up the sector through free trade will yield an economic benefit amounting to P138.5 billion. On the other hand, increasing the import quota would lead to about P25.2-billion increase in economic surplus.

Free trade is undeniably detrimental to farmers; the simulation shows that they will lose the equivalent of P34 billion. However the benefits to consumers is large, and net benefit to society is still large as mentioned above. Gradual reform can be implemented by converting the import quota into tariff protection, with a moderate level of tariff. This tarrification should be accompanied by producer support policies to avoid severe dislocation. Such policies are expected to strike a balance between the welfare of producers and those of consumers; in the end, the essence of food security is consistent access to affordable food.

Roehlano Briones and Lovely Ann Tolin are fellows from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies. This piece was adapted from CREW Diagnostic Country Report: Philippines, a study conducted by PIDS with financial and technical support from the Centre for Competition, Investment and Economic Regulation (CUTS-CIER), Jaipur, India. //