Recently, the Department of Education (DepEd) authorized its regional units to begin the progressive expansion of face-to-face classes in public schools found in areas under Alert Levels 1 and 2 for COVID-19. This means that more grade levels could soon be included in this expansion.

After two years of community quarantines, the reopening of our schools is a welcome development. According to recent DepEd data, some 304 schools are eligible to restart face-to-face classes. With pediatric vaccinations now ongoing and steadily ramping up across the country, the immediate concern is on how the remaining 47,000 public schools, 12,000 private schools, and more than 200 public universities could be supported so that they too can reopen sooner rather than later.

Bigger questions however will need to be answered. What kind of education system will our children be returning to once the pandemic ends? Are they still on track or will steps have to be taken for them to catch up?

Truly, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted so many parts of our society. Not only did it introduce new challenges, it also exacerbated the old ones. And sadly, among the worst-hit is our education sector.

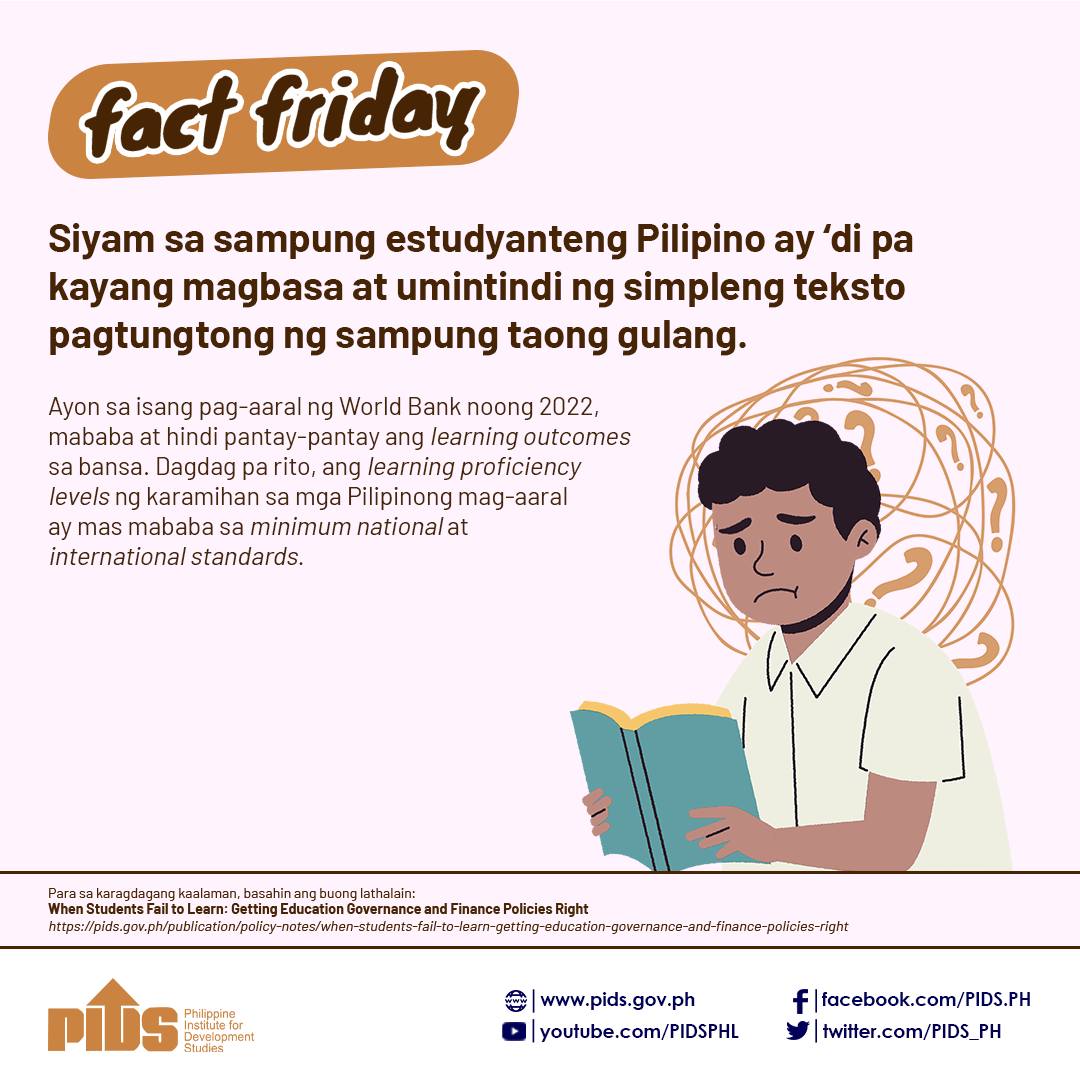

In November 2021, the World Bank reported that 90 percent of our 10-year-olds were possibly thrust into “learning poverty” because of the pandemic, such that they do not know how to read and understand a simple passage of text. The report surmised that this is because of the vast inequalities faced by our students. For instance, not all households have access to smartphones, laptops, tablets or gadgets for remote learning. Neither do all have stable Internet connections.

Clearly, the country is in the middle of a learning crisis. But it would be misguided to think that such was caused by the pandemic. Our education system’s underperformance had already been observed even before COVID-19 hit.

In the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) to which we volunteered to be included for the first time, our students attained the lowest score for reading, and second to the lowest for science and mathematics, out of the 79 countries and economies surveyed.

These findings prompted Senate Minority Leader Franklin Drilon, Basic and Higher Education Committee chairs Sherwin Gatchalian and Joel Villanueva, Senators Grace Poe and Imee Marcos, and myself to file in December 2019 a resolution calling for the establishment of a Congressional Commission on Education or EDCOM.

This is similar to the commission headed by my late father former Senate President Edgardo J. Angara in 1989, whose terminal report led to the establishment of our existing trifocalized system. Like its predecessor, this EDCOM 2 will study and assess the current performance of the education system to recommend policy and legislative reforms and other actionable items that would improve its performance.

This isn’t to deny however the many positive developments in Philippine education in recent years, such as the enactment of the Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act, which made college tuition free in all state universities and colleges, including some that are run by our local government units.

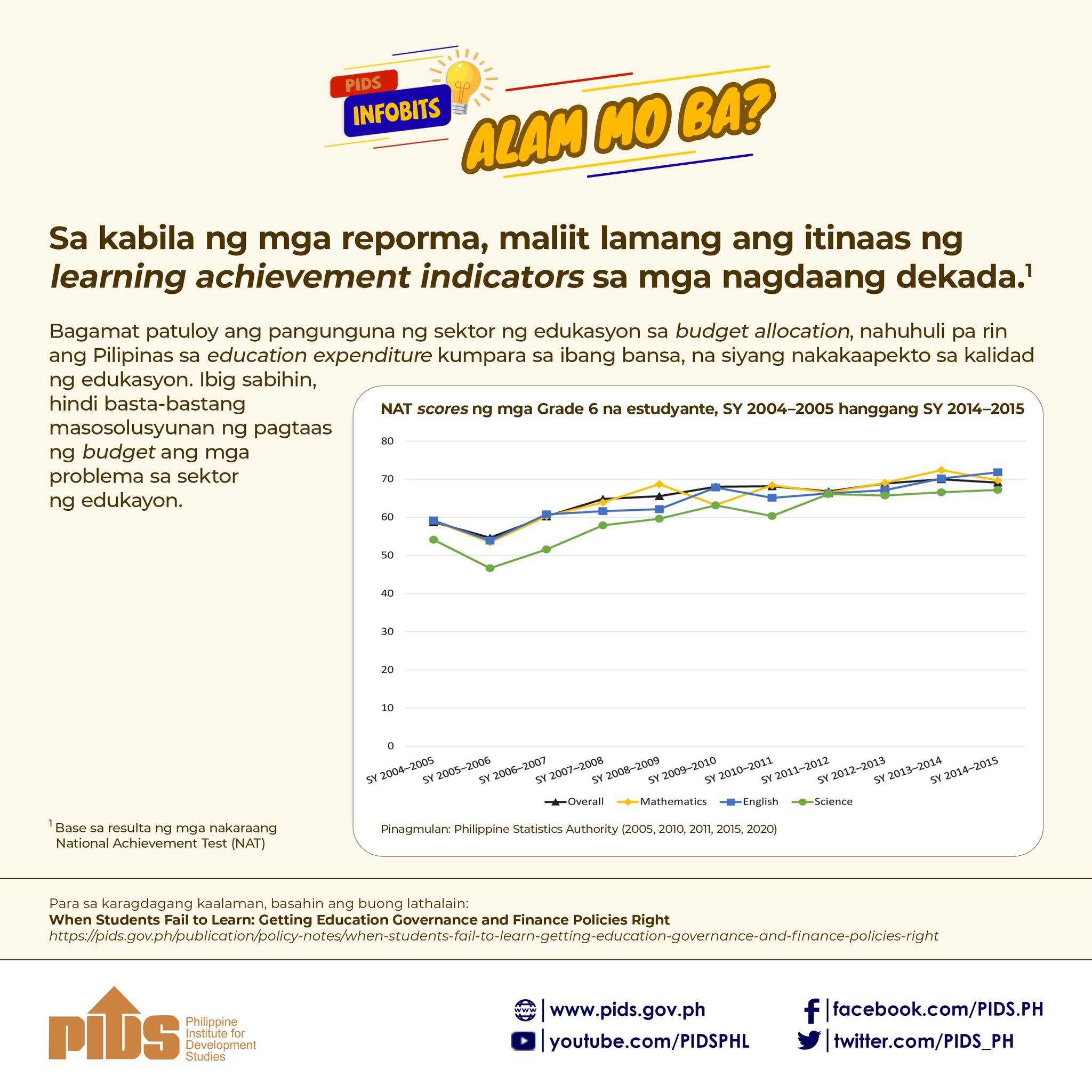

Government expenditure for education has also continued to increase, though still has some ways to go before becoming comparable to our regional peers and aligned with global standards. This was affirmed by a December 2021 Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) discussion paper, showing that public expenditure for education (sans capital outlay investments) grew from P198.5 billion in 2005 to P531.1 billion in 2019. This meant that public sector spending on education increased from 2.1 to 3.1 percent of GDP within that period — a significant jump no doubt, but still below the 4 to 6 percent global benchmark.

While it would be ideal if public expenditures on education could be ramped up, this is not easily done, especially with the immense fiscal pressures brought about by the pandemic, not to mention a growing population. Add to that the need to keep up with the demands of the fast-changing world, and the imperative to come up with a national vision and a strategic plan for improving education becomes clear.

We are happy to note that before the Senate went into recess earlier this month, it already passed the measure principally authored by my seatmate Senator Gatchalian to create EDCOM 2. A bicameral conference committee between the House and the Senate has yet to be convened, but we are hopeful that once Congress resumes in May, this legislative measure will be approved and immediately sent to the Executive for the President’s signature. Its enactment is extremely crucial for the future of youth, and in turn, of our post-pandemic recovery.