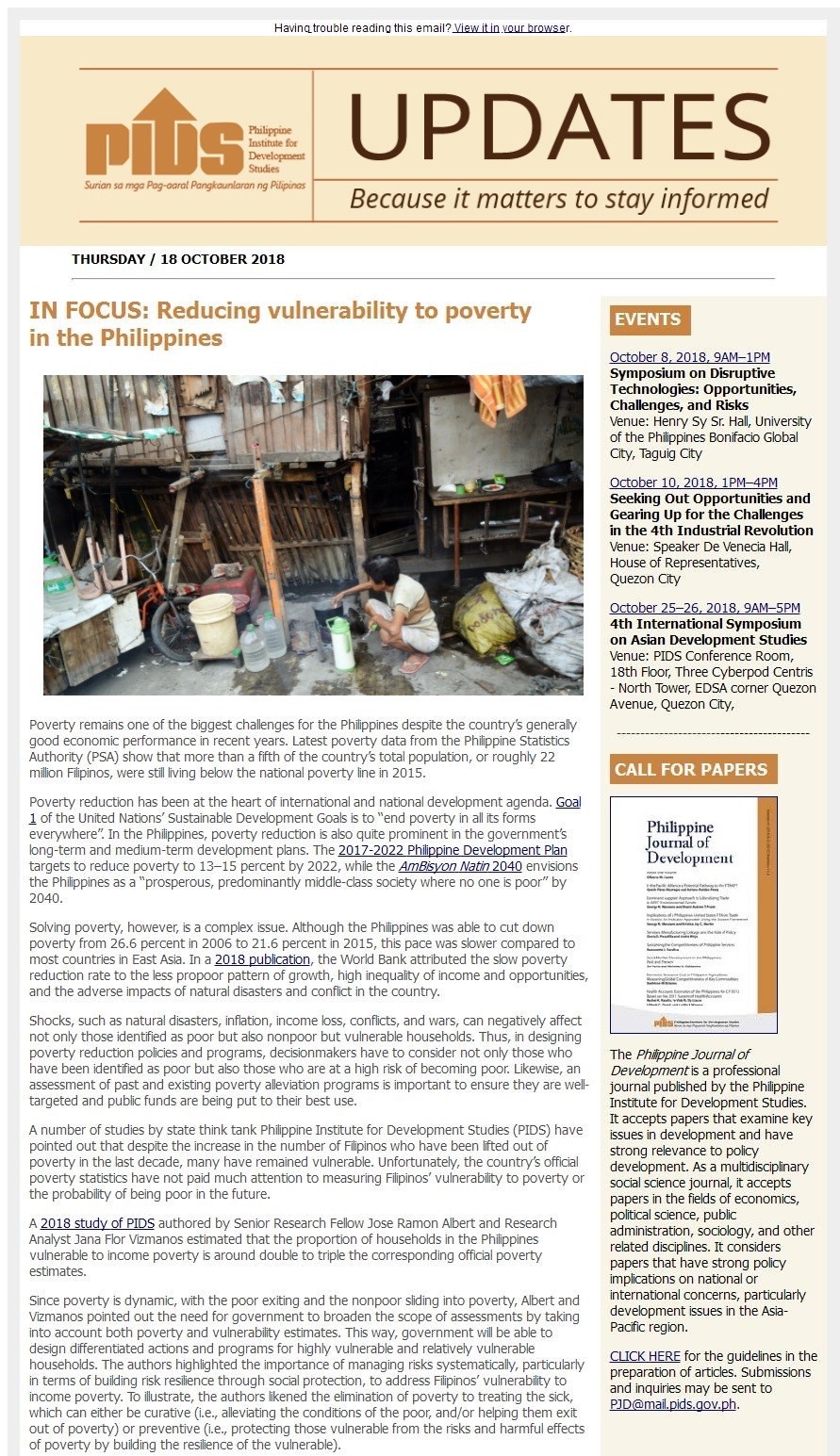

Poverty reduction has been at the heart of international and national development agenda. Goal 1 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals is to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere”. In the Philippines, poverty reduction is also quite prominent in the government’s long-term and medium-term development plans. The 2017-2022 Philippine Development Plan targets to reduce poverty to 13–15 percent by 2022, while the AmBisyon Natin 2040 envisions the Philippines as a “prosperous, predominantly middle-class society where no one is poor” by 2040. Solving poverty, however, is a complex issue. Although the Philippines was able to cut down poverty from 26.6 percent in 2006 to 21.6 percent in 2015, this pace was slower compared to most countries in East Asia.

In a 2018 publication, the World Bank attributed the slow poverty reduction rate to the less propoor pattern of growth, high inequality of income and opportunities, and the adverse impacts of natural disasters and conflict in the country. Shocks, such as natural disasters, inflation, income loss, conflicts, and wars, can negatively affect not only those identified as poor but also nonpoor but vulnerable households. Thus, in designing poverty reduction policies and programs, decisionmakers have to consider not only those who have been identified as poor but also those who are at a high risk of becoming poor. Likewise, an assessment of past and existing poverty alleviation programs is important to ensure they are well-targeted and public funds are being put to their best use.

A number of studies by state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) have pointed out that despite the increase in the number of Filipinos who have been lifted out of poverty in the last decade, many have remained vulnerable. Unfortunately, the country’s official poverty statistics have not paid much attention to measuring Filipinos’ vulnerability to poverty or the probability of being poor in the future.

A 2018 study of PIDS authored by Senior Research Fellow Jose Ramon Albert and Research Analyst Jana Flor Vizmanos estimated that the proportion of households in the Philippines vulnerable to income poverty is around double to triple the corresponding official poverty estimates.

Since poverty is dynamic, with the poor exiting and the nonpoor sliding into poverty, Albert and Vizmanos pointed out the need for government to broaden the scope of assessments by taking into account both poverty and vulnerability estimates. This way, government will be able to design differentiated actions and programs for highly vulnerable and relatively vulnerable households. The authors highlighted the importance of managing risks systematically, particularly in terms of building risk resilience through social protection, to address Filipinos’ vulnerability to income poverty. To illustrate, the authors likened the elimination of poverty to treating the sick, which can either be curative (i.e., alleviating the conditions of the poor, and/or helping them exit out of poverty) or preventive (i.e., protecting those vulnerable from the risks and harmful effects of poverty by building the resilience of the vulnerable).

These recommendations also support a 2017 PIDS study by PIDS President Celia Reyes and former Supervising Research Specialist Christian Mina. The authors noted that building resilience in coping with shocks and enhancing social protection and access to basic services are necessary to address vulnerability and inequality. They maintained that government can devise comprehensive strategies related to risk prevention, mitigation, and management, including strengthening of early warning and forecasting systems.

For example, a 2017 study by PIDS Senior Research Fellow Connie Dacuycuy and Research Analyst Lora Kryz Baje found that chronic food poverty is higher in households that have experienced rainfall deviation than those that have not. To address the adverse effect of sustained weather fluctuations, this study urges local government units to invest in developing climate-smart agriculture that fits the needs of the community. It also calls for the government to explore adaptive social protection initiatives that support propoor climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction by strengthening the resilience of vulnerable populations to shocks.

Examining data on both poverty and vulnerability in formulating risk resilience measures will allow vulnerable households to reduce the effects of adverse events such as natural calamities, price shocks, and idiosyncratic shocks, on their conditions. It will also empower them to seize the moment and take advantage of opportunities for improving their prospects for a better future today.

PIDS has long been active in conducting rigorous analyses of the causes and impact of poverty, inequality, economic disparity, and related issues. You may access these studies from the Socioeconomic Research Portal for the Philippines. Simply type ‘poverty’, ‘inequality’, ‘vulnerability’, ‘social protection’, ‘resilience’, and other relevant keywords in the Search box.