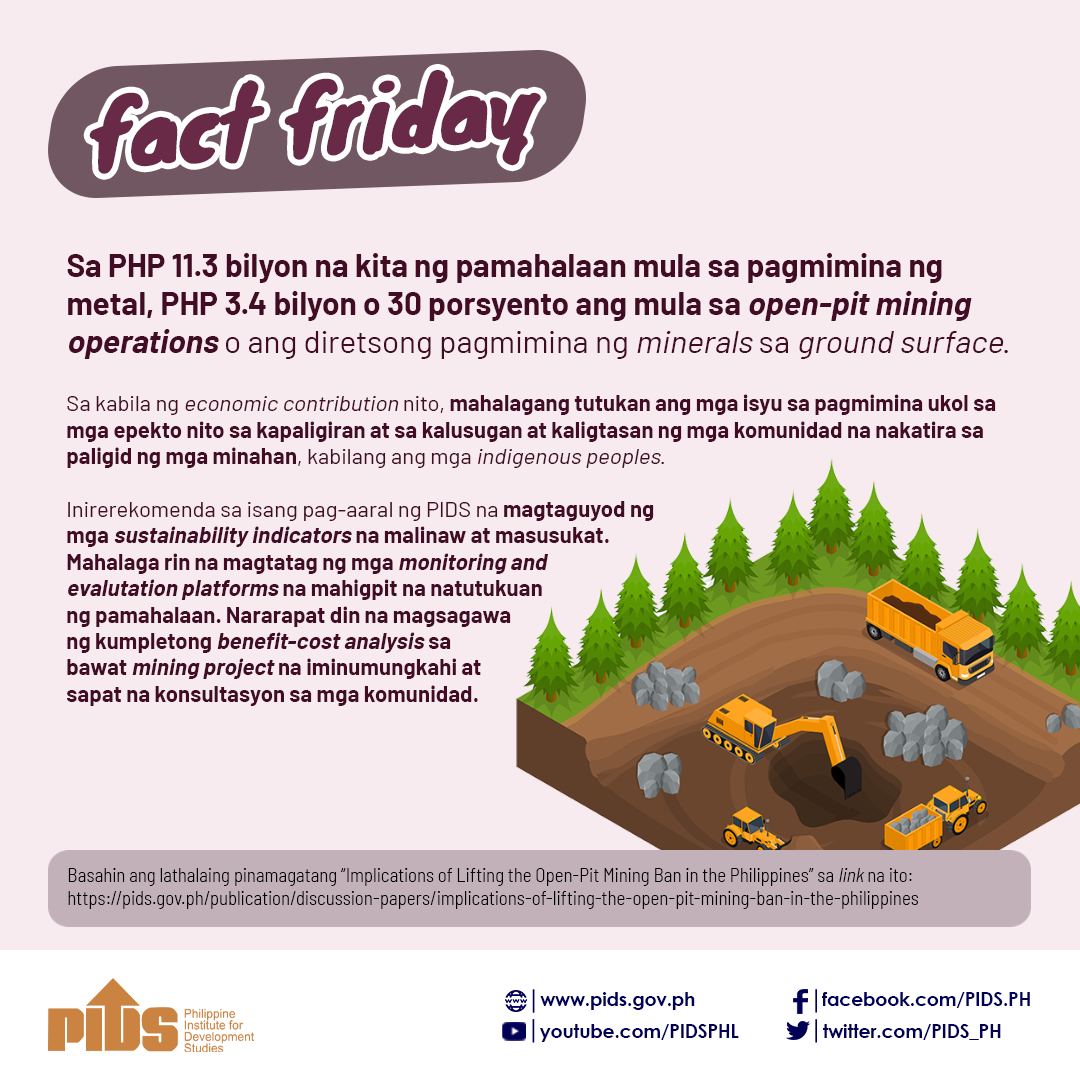

State-run think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) has recommended the amendment of the Small-Scale Mining Act to formalize small-scale mining in the country and prevent industry outputs from disappearing in the black market.

In a Policy Note, titled “Bottlenecks to formalization of Small-Scale Mining in the Philippines,” PIDS Senior Fellow Sonny N. Domingo and Research Analyst Arvie Joy A. Manejar said “testaments on the ground” claim that small-scale mining accounted for 70 percent of the country’s total mining output.

Domingo and Manejar said amendments in the law should include a definition of small-scale mining and that subsector stakeholders should be made accountable to the public, the government, and environment.

“The different aspects of formalization should be addressed through a cohesive and comprehensive strategic framework, which should be anchored on clear policy. This would entail the passing of a new legislation that fills in the weaknesses of the current law,” Domingo and Manejar said.

Based on the law, the authors said, small-scale mining activities use manual labor and do not rely on heavy mining equipment. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development also have a similar definition.

However, Domingo and Manejar said this no longer mirror the actual situation on the ground. Currently, small mining operations already employ heavy machinery and modern technology, such as heavy equipment, explosives and chemicals.

Further, they also pointed out that there’s a conflict between the law and the Minahang Bayan activities. under the Minahang Bayan guidelines since local government units (LGUs) do not recognize the Minahang Bayan without clearance from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

“As such, there are Minahang Bayans that are locally declared, but are technically still illegal in designation. The devolution of regulatory functions has to be cleared between LGUs and the national government,” the authors said.

Apart from the amendment of the law, Domingo and Manejar suggested the passing of legislation that will rationalizes taxation in the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’ (BSP) gold-buying activities.

The legal sale of gold from small-scale mining is done only through the BSP. However, the authors said there is a need to create an accreditation scheme by BSP for gold buying centers.

“This can also invigorate value-adding through other industries, such as jewelry-making which has an immense potential contribution to the economy,” they said. “(This) promises the recapture of sales lost through the black market,” they added.

The authors also recommended that a proper census be done to capture the extent of small-scale mining in the Philippines.

This will help ensure worker protection and capture the benefits of the industry on the economy. The census must include demographic information of the stakeholders, particularly the detailed profiles of mining operators and laborers.

The census should capture information about households and the details of workers. These details include incomes and expenditures, employment arrangements, and mining agreements.

Domingo and Manejar also said the census should also capture specifics of mineral production, such as volume and value of minerals, risk assessment, and market pathways.

“Albeit relatively unseen, it still contributes to the national and local economies through the circulation of resources and the employment of thousands of Filipinos. It is time that the bureaucracy put a stop to these losses and ensure that industry outputs do not disappear through the black market,” they said.

Data showed that the mining industry contributed around 0.8 percent to the Philippines’ gross domestic product in 2018. In that year, the mining sector’s production value reached P179.6 billion and employed at least 207,000 people.

However, Domingo and Manejar said these figures are conservative estimates and that the benefits from mining operations and production are not well documented.

In a Policy Note, titled “Bottlenecks to formalization of Small-Scale Mining in the Philippines,” PIDS Senior Fellow Sonny N. Domingo and Research Analyst Arvie Joy A. Manejar said “testaments on the ground” claim that small-scale mining accounted for 70 percent of the country’s total mining output.

Domingo and Manejar said amendments in the law should include a definition of small-scale mining and that subsector stakeholders should be made accountable to the public, the government, and environment.

“The different aspects of formalization should be addressed through a cohesive and comprehensive strategic framework, which should be anchored on clear policy. This would entail the passing of a new legislation that fills in the weaknesses of the current law,” Domingo and Manejar said.

Based on the law, the authors said, small-scale mining activities use manual labor and do not rely on heavy mining equipment. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development also have a similar definition.

However, Domingo and Manejar said this no longer mirror the actual situation on the ground. Currently, small mining operations already employ heavy machinery and modern technology, such as heavy equipment, explosives and chemicals.

Further, they also pointed out that there’s a conflict between the law and the Minahang Bayan activities. under the Minahang Bayan guidelines since local government units (LGUs) do not recognize the Minahang Bayan without clearance from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

“As such, there are Minahang Bayans that are locally declared, but are technically still illegal in designation. The devolution of regulatory functions has to be cleared between LGUs and the national government,” the authors said.

Apart from the amendment of the law, Domingo and Manejar suggested the passing of legislation that will rationalizes taxation in the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’ (BSP) gold-buying activities.

The legal sale of gold from small-scale mining is done only through the BSP. However, the authors said there is a need to create an accreditation scheme by BSP for gold buying centers.

“This can also invigorate value-adding through other industries, such as jewelry-making which has an immense potential contribution to the economy,” they said. “(This) promises the recapture of sales lost through the black market,” they added.

The authors also recommended that a proper census be done to capture the extent of small-scale mining in the Philippines.

This will help ensure worker protection and capture the benefits of the industry on the economy. The census must include demographic information of the stakeholders, particularly the detailed profiles of mining operators and laborers.

The census should capture information about households and the details of workers. These details include incomes and expenditures, employment arrangements, and mining agreements.

Domingo and Manejar also said the census should also capture specifics of mineral production, such as volume and value of minerals, risk assessment, and market pathways.

“Albeit relatively unseen, it still contributes to the national and local economies through the circulation of resources and the employment of thousands of Filipinos. It is time that the bureaucracy put a stop to these losses and ensure that industry outputs do not disappear through the black market,” they said.

Data showed that the mining industry contributed around 0.8 percent to the Philippines’ gross domestic product in 2018. In that year, the mining sector’s production value reached P179.6 billion and employed at least 207,000 people.

However, Domingo and Manejar said these figures are conservative estimates and that the benefits from mining operations and production are not well documented.