INCREASING food production to feed more than 100 million Filipinos has become more challenging due to changing weather patterns, as well as the continuous conversion of farm lands. The Philippine Rice Research Institute (PhilRice) said it doesn’t help that farmers also have to deal with the "inherent disadvantages” of the Philippines.

In Photo: Manuel Chase M. Castaño III, science research analyst, Be RICEponsible Campaign; Dr. Calixto M. Protacio, executive director, DA- PhilRice; Jaime Manalo, head, Development Communications Division; and Dr. Santiago Obien, special technical assistant to the National Rice Program, during the BM Coffee Club Forum.

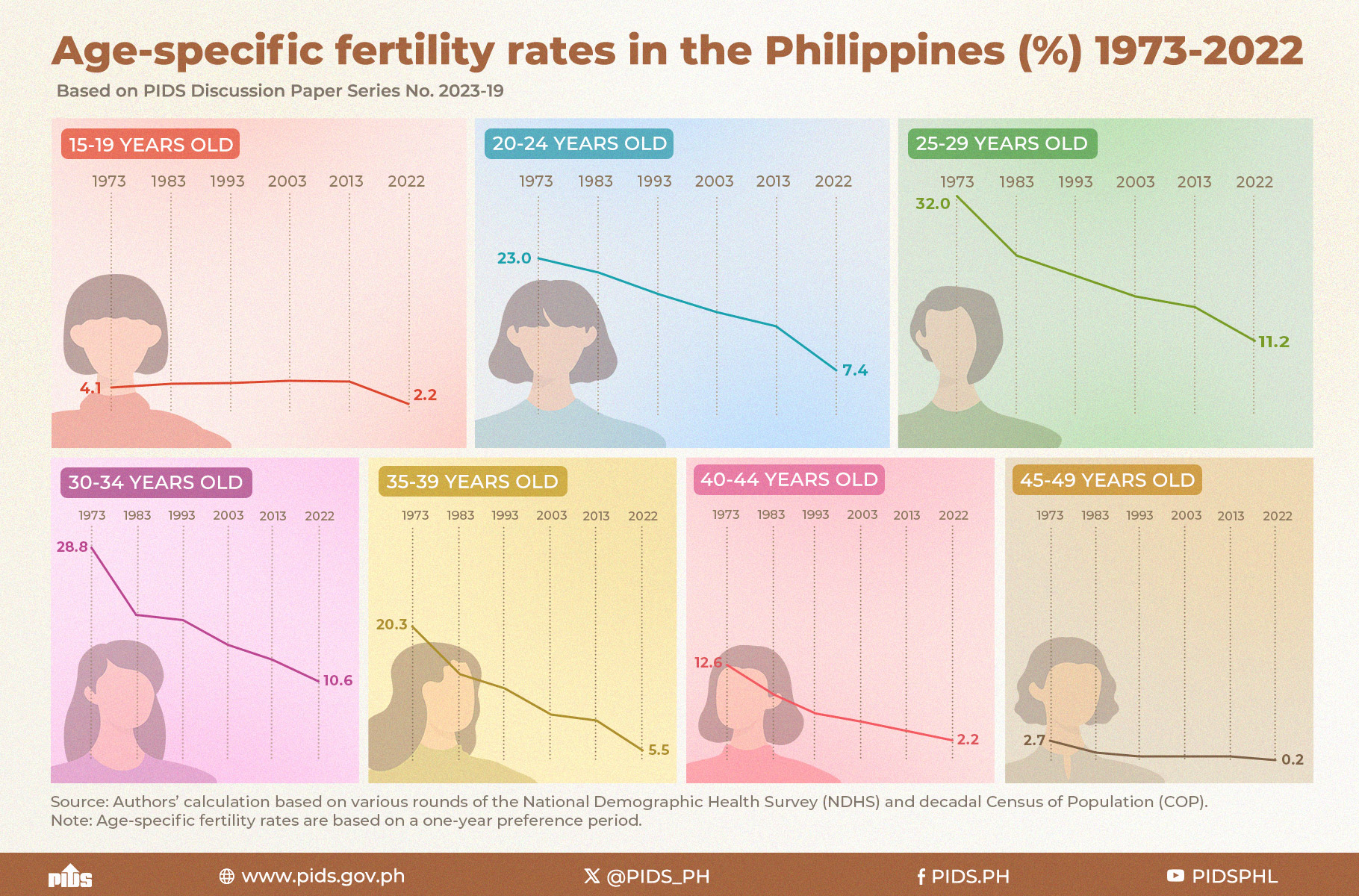

As rice is the staple food of Filipinos, farmers are under pressure to expand rice output every year. Paddy-rice output needs to keep pace with population growth, pegged at nearly 2 percent annually.

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the country’s population increased at the rate of 1.9 percent annually, on the average, during the period 2000 to 2010. This means that there were two persons added per year for every 100 persons in the population.

Meanwhile, annual per-capita consumption of rice was pegged by the PSA at 114.27 kilograms. This means that each Filipino consumes about 2.2 kg of rice per week.

Because of the importance of rice to the Filipinos’ diet, the Philippines has 2.6 million hectares of land devoted to rice. The average farm size is at 1.04 hectares, while harvest area is at 4.7 million hectares.

Dr. Santiago R. Obien, senior technical adviser of the Department of Agriculture’s (DA) National Rice Program, said farmers’ adoption of technological innovations would help them become more productive.

One such technology is hybrid-rice seeds, which would allow farmers to grow more rice and consequently earn more. The country’s hybrid-rice varieties, Obien said, are the best outside of China, as yield could average 8 to 10 tons per hectare, and can reach up to 12 tons.

"As a farmer’s yield increases, his cost of production decreases. This would allow farmers to increase their profits,” Obien told reporters and editors during a forum, dubbed as the BM Coffee Club, held recently in Makati City.

Economies of scale

PhilRice Executive Director Calixto M. Protacio and Obien both agree that there should be farm areas consolidated and managed by fewer farmers to again make farming a "financially appealing and viable venture.”In economically advanced countries, Obien said only about 3 percent of the total population are farmers. Korean farmers in 1960 used to make up 53 percent of their population. Now, there are only 16 percent of these farmers, and they are rich.

Obien also noted that the number of farmers in Thailand is also declining, as many of them are being recruited by factories. Some of these farmers ask their neighbors to take care of their farms.

"If one farmer has 4 hectares of land and two of his friends who also have 4 hectares each go into other industries and ask him to cultivate their land, that farmer now has 12 hectares to harvest. With bigger land, that farmer can now buy a tractor and a [vehicle]. It just shows that we need less farmers to be rich,” Obien said.

For his part, Protacio said there is a need to achieve economies of scale for farmers to make them more productive and competitive. He said farmers with a small land cannot afford to adopt innovations to make farming efficient and increase their output.

"Clustering, or land consolidation, is good. You have to establish economies of scale. In a way, the idea is to go back to the concept of landlords. We are looking at this as a rural-transformation idea. We found that to be able to become a millionaire, a farmer has to have at least 20 hectares of land,” he said.

In their study, "The Size Distribution of Farms and International Productivity Differences” published in 2011, Tasso Adamopoulos and Diego Restuccia focused on the differences in average farm sizes among countries. They found that the average farm size for poor countries is 1.6 hectares, while rich countries have an average farm size of 54.1 hectares.

"Richer countries have fewer small farms and more large farms than poorer countries. In the poorest countries, over 90 percent of farms are small and almost none of the farms are large; whereas in the richest countries, small farms account for about 30 percent of farms and large farms for nearly 40 percent,” the study read.

A recent study by Krishna H. Koirala and Ashok K. Mishra of the Louisiana State University and Samarendy Mohanty of the International Rice Research Institute, titled "Impact of Land Ownership on Productivity and Efficiency of Rice Farmers: A Simulated Maximum Likelihood Approach,” revealed that a 1-percent increase in farm size could result in an increase in the value of rice production by about 0.4 percent.

CARP’s woes

The Philippine government, nonetheless, still has a commitment to grant landless farmers and farm workers ownership of agricultural lands by the end of the Aquino administration. Farm lands are becoming more fragmented into smaller areas as they are being turned over to small farmers.

Republic Act (RA) 6657, or the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law, was enacted by President Corazon Aquino in 1988, authorizing the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) to undertake the distribution of an estimated 7.8 million hectares of agricultural lands.

The law was aimed to promote social justice and to establish "owner cultivatorship” of economic-size farms as the basis of Philippine agriculture.

"To this end, a more equitable distribution and ownership of land, with due regard to the rights of landowners to just compensation and to the ecological needs of the nation, shall be undertaken to provide farmers and farm workers with the opportunity to enhance their dignity and improve the quality of their lives through greater productivity of agricultural lands,” RA 6657 stated.

However, Obien said the government has failed to follow the distribution of land with the provision of farm inputs and machineries. He said the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) of the government has not served as a plan for productivity.

"It [CARP] was simply a social-justice system. That’s the problem. It should not have been that way. It should have been a systematic program so that farmers can become more productive,” Obien said.

"The government, upon the release of the land, should have also provided the farmers with machineries, facilities, inputs and electricity, among others, so that they can be progressive. The Japanese call it land reformation, not land reform. However, nothing was given to our farmers,” he added.

Protacio said the initial idea for the CARP was for cooperatives to take over the farmlands and consolidate them into large units. He said, however, that because of the individualistic nature of Filipinos, it did not work.

In 1996 the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) also published a study, titled "Issues in Revitalizing the Philippine Sugar Industry.” The study revealed that the sugar industry had to contend with declining productivity.

"Implementing the land-transfer scheme of CARP had been slow due to the government’s administrative and financial constraints. And then there is the strong opposition from the landowners. Nonland-transfer schemes, which include land lease or rental, profit sharing and corporate stock distribution, have proven to be unattractive to landowners,” the study read.

"Such delay and uncertainties discourage CARP farmer-owners to invest in farm improvements, lower collateral value of agricultural land, and reduce credit flow to agriculture. In the end, low productivity becomes inevitable,” it added.

A study published by the International Society for Southeast Asian Agricultural Sciences (ISSAAS), titled "Farm Size and Its Effect on the Productive Efficiency of Sugarcane Farms in Central Negros,” showed that average optimum land size should be around 41 hectares, which is lower than the optimum size (50 hectares) stated in the report of the Presidential Task Force on the Sugar Industry.

"[Big farms] are also the more favored in terms of technology and access to information and extension services. Modernization of farm practices can improve productive efficiency, however, this is difficult to achieve at present due to the limited financial capability of the farmers,” the report read.

To boost the productivity of sugarcane farms, the Sugar Regulatory Administration (SRA) rolled out a program, which sought to consolidate small farms into larger areas while still preserving individual ownership of the land, in 2012.

"Block farming is the consolidation of the management of small farms of less than 5 hectares, into a bigger but contiguous unit of at least 30 hectares for purposes of improving farm productivity, while individual ownership is preserved,” SRA Administrator Ma. Regina Martin said in a statement.

Data from the SRA showed that about 85 percent of the sugarcane farms in the country have areas of 5 hectares or below. The SRA said this is due to the natural course of land subdivision by inheritance, sale and the CARP.

According to the SRA, sugarcane is a plantation crop and its cost efficiency is best achieved through bigger farm sizes of at least 30 hectares. However, with the implementation of the CARP, farm sizes were fragmented into small land holdings of less than 5 hectares, wherein farm owners could no longer take advantage of economies of scale.

Present land owners also do not have the financial capability to provide farm inputs, which results in low productivity, the SRA said.

Since its implementation in 2012, SRA said the 19 pilot block farms have registered an average increase of 29 percent in farm productivity in crop year 2013 and 2014. Sugar production in the pilot farms in that crop year reached 65.29 tons cane per hectare, as compared to 50.78 tons cane per hectare recorded in 2012.

This increase in productivity translated to an estimated average increase of farmers’ income by P39,815 per hectare, at 1.96 50-kilogram per tons cane (LKG/TC) and a composite price of P1,400 per LKG-bag of raw sugar.

Aside from consolidating small farms into an aggregate of at least 30 hectares–through agrarian reform beneficiaries organizations–the SRA also offers coached and guided farm management, technical assistance and capacity building for the farmers in a block farm. The DA also provides irrigation systems, farm-to-market roads and farm inputs necessary for the production of sugarcane.

The program has now become one of the main programs under RA 10659, or the Sugar Industry Act of 2015. The SRA said there are 130 block farms that have enrolled for accreditation to date, with a total area of about 7,000 hectares.

Protacio said the SRA’s block farming scheme could also be adopted by other sectors.

Agriculture Secretary Proceso J. Alcala, for his part, said the DA has also put up block farms for the rice sector. He said, however, that it has not been as successful as the program rolled out for sugarcane farmers.

"What’s important is we integrate our palay farmers. We have partnered with the DAR in implementing block farming in some areas,” Alcala said.

"Agrarian-reform communities should have been created long ago. They should have started block farming long ago. Block farms have the advantage because they have all these tools and resources to use so that they can be progressive,” Obien said. //