via rappler.com – The Philippines will transition to an ageing society by 2032, and for the economy, this could be both boon and bane, according to a study of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

A December 2018 PIDS study dove into United Nations data from 2017 to project that the Philippines was on its way to becoming an “ageing society.”

This means that by 2032, the elderly, or those aged 65 and older, would comprise at least 7% of the total population.

By 2069, the study said, the Philippines would have become an “aged society,” with at least 14% of the population aged 65 or older.

“Population ageing is not a bad thing. It represents a story of our collective success as Filipinos. It means that we are able to conquer the challenges such as those related to income, health, and education,” said PIDS research fellow Michael Abrigo, one of the proponents of the study.

The idea of ageing and rising life expectancy may also lead to higher savings and investment and may result in faster economic growth and improved living standards, he said.

“Because we expect a longer lifespan, we also tend to save more, and this leads to greater productivity,” said Abrigo.

There is a flip side to this, however, as an ageing society could imply declining income tax, health insurance premiums, and pension contributions.

“More elderly people means more subsidies for healthcare expenses. Moreover, the elderly tend to have medical conditions that are more expensive on the average,” Abrigo said.

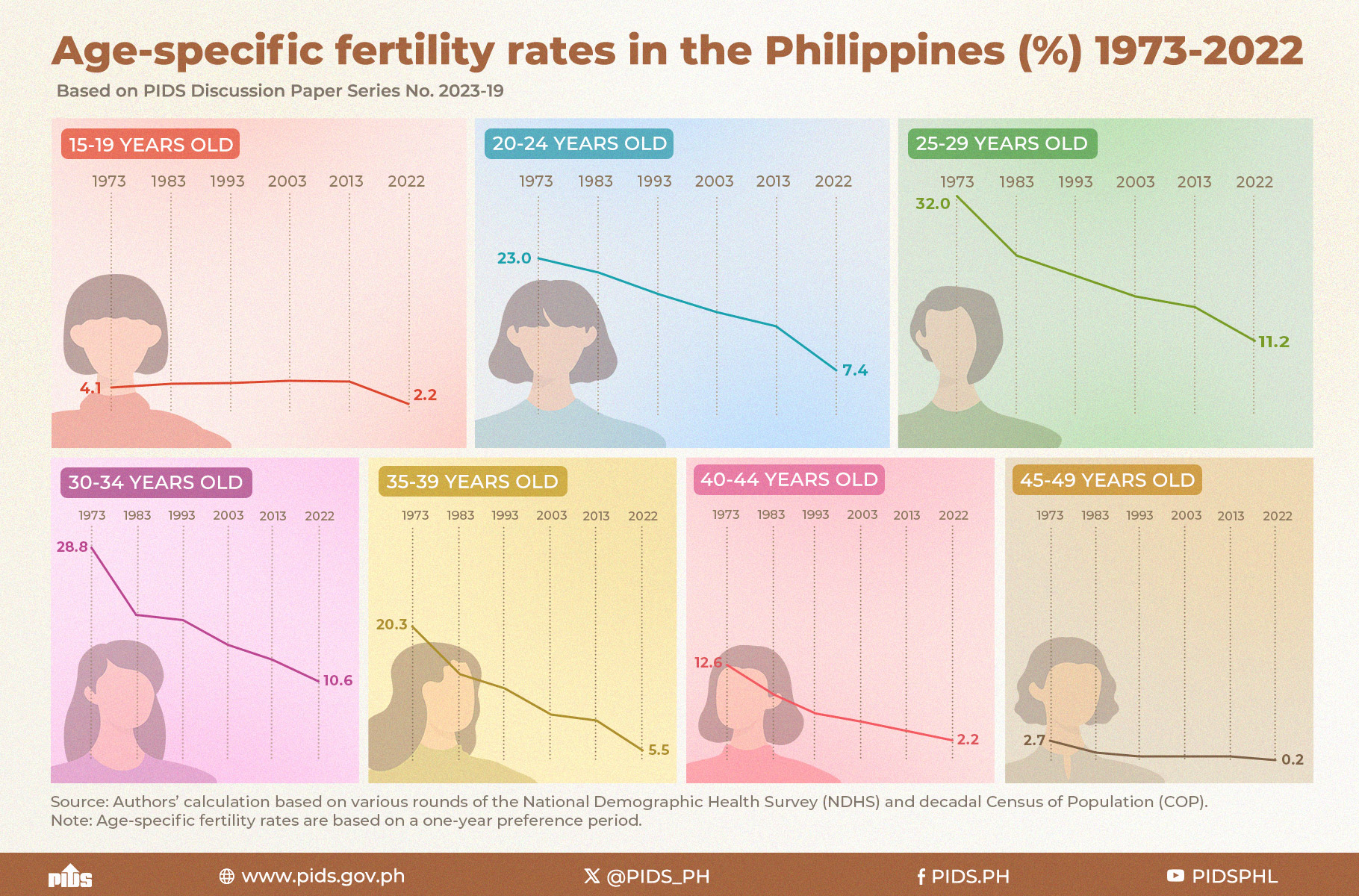

The projection of a slowly ageing Philippine society is based on current demographic trends that showed “a slow but steady decline” in fertility rates in the past 25 years.

According to the PIDS study, as fertility rates drop, the population becomes concentrated among working ages, raising the average incomes per person. A drop in fertility also implies that parents have to care for fewer children, allowing greater human capital investments for each child and increasing their productivity once they join the workforce.

The study said, however, that uneven decline in fertility rates could worsen inequality. A policy implication of this could be that the government continue cash transfer programs to ensure that no one gets left behind. But the study also warned that such cash transfer programs could also lead to unsustainable public debt burden in the long run.

“Maybe this generation is very lucky because we all have these free public services such as free healthcare, free basic education, as well as free college education. But these paying consumers will grow old and someone else will have to pay for these freebies in the future,” Abrigo cautioned.

The government should then not only look at income inequality but generational equity as well, said Abrigo. He also recommended that public policies that promote growth and employment be continuously put in place.