The Philippines falls behind its ASEAN counterparts in critical health outcomes and access indicators.

This is according to a discussion paper published by state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

PIDS Research Fellow Valerie Gilbert T. Ulep and PIDS Research Analyst Lyle Daryll D. Casas said “this reflects the longstanding challenges in terms of health financing, health service delivery, governance, and health human resources.”

Ulep and Casas pointed out that health systems must have sufficient health facilities offering different types and levels of health services.

However, this is not the case in the Philippines.

Hospital beds are limited. Based on 2020 data from the Department of Health (DOH), 400,000 hospital beds are needed to meet the population need for hospital care (or about 2.7 beds per 1,000 population).

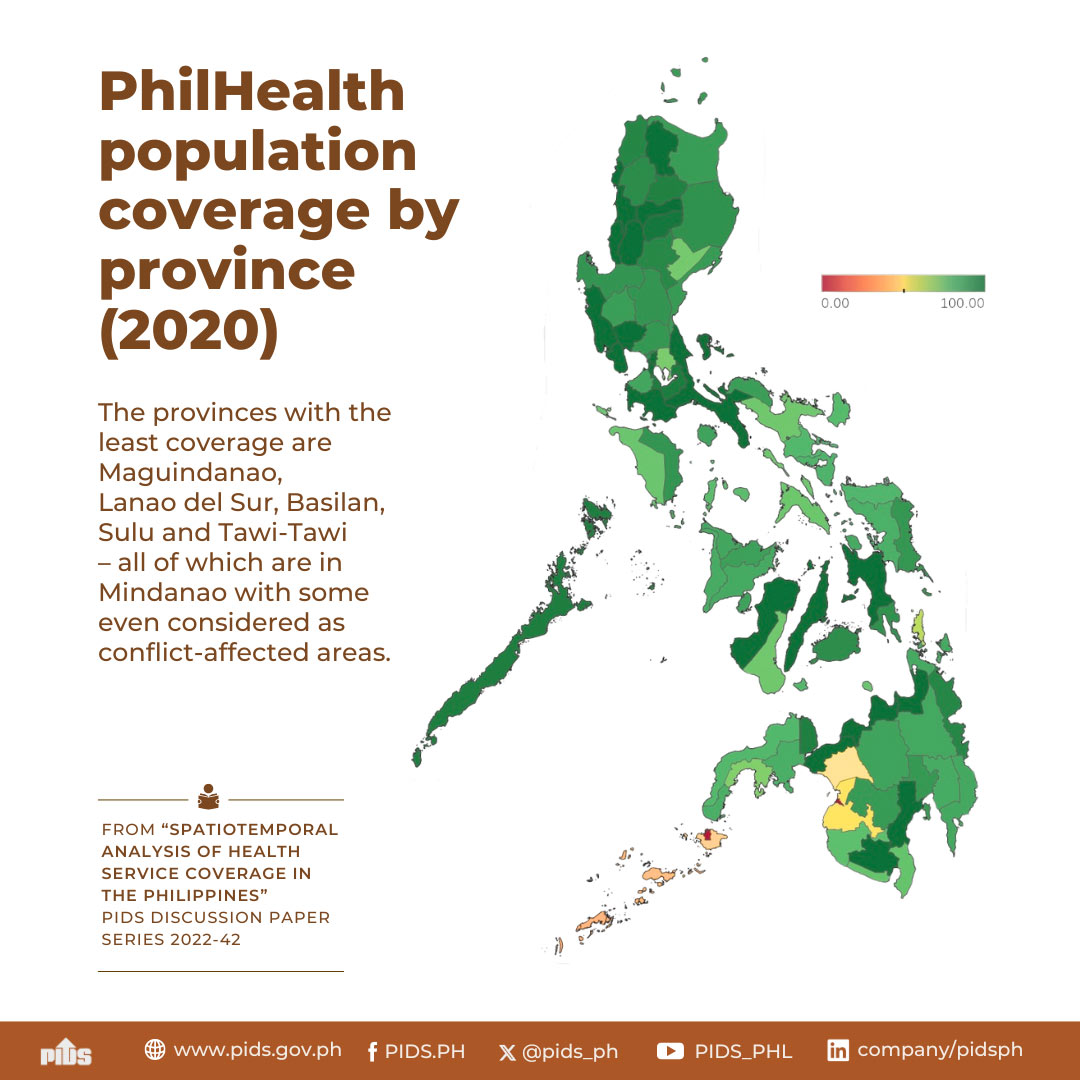

About half of Filipinos do not have timely access to primary healthcare facilities. In 2020, only 50 percent of Filipinos were able to access primary health care within the standard time frame set by the government, which is 30 minutes.

Ulep and Casas added that public health spending in the Philippines is one of the lowest in the ASEAN region.

A World Health Organization (WHO) report showed that the country spends only about 1.5 percent of its gross domestic product on health, which is significantly lower than that of Thailand, Viet Nam, Singapore, and Malaysia.

The country also lacks health human resources. Based on DOH’s health facility survey in 2019, only 90 percent of rural health units or primary healthcare facilities have at least one medical doctor, while a significant number of health facilities do not have a nurse or a midwife.

In terms of preparedness for public health emergencies, the Philippines received an average score of 53 percent from WHO’s International Health Regulations (IHR), making it one of the poorest performing countries in the region next to Lao PDR and Cambodia. The IHR monitors the capabilities of a country’s health system to detect, assess, and notify public health risks and emergencies of national and international interest, including pandemics.

To address these challenges, Ulep and Casas provided some recommendations.

One is for the government to attract domestic and foreign investments to finance and close the country’s health infrastructure gap in the medium and long term. This can be done by increasing the equity threshold for hospital foreign investments to 100 percent, imposing additional tax breaks for hospital investments, and accelerating investment approvals for health services and medical equipment, among others.

They also urged the government to develop and implement a well-thought-out medical tourism program that could bring in revenues to finance the universal health care program.

The government should also adopt digital reforms in providing health services. Ulep and Casas urged Congress to support the eHealth Systems and Services Bill to serve as the regulatory framework and to institutionalize telemedicine domestically, especially during the pandemic.

“This should be supported by comprehensive clinical practice guidelines, especially in the practice of teleconsultations,” they said.

They also suggested ways to facilitate the mainstreaming of digital health like providing capacity-building activities for medical workers and their administrative staff, incorporating telemedicine in medical education and training curricula, and giving certificates for telemedicine practice in continuing professional development.

Ulep and Casas also stressed the need to implement robust domestic reforms to liberalize the country for cross-border health integration.

“Pushing for regional health integration will be relevant to the country’s pursuit of universal health care, and openness to regional integration may be a way for the domestic system to be resilient in facing disasters (e.g., pandemics) and to foster effective health crisis management and achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3, which is to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all and at all ages,” they said. ###

This article is based on the PIDS Discussion Paper titled “Regional Health Integration and Cooperation in the Philippines”.

This is according to a discussion paper published by state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

PIDS Research Fellow Valerie Gilbert T. Ulep and PIDS Research Analyst Lyle Daryll D. Casas said “this reflects the longstanding challenges in terms of health financing, health service delivery, governance, and health human resources.”

Ulep and Casas pointed out that health systems must have sufficient health facilities offering different types and levels of health services.

However, this is not the case in the Philippines.

Hospital beds are limited. Based on 2020 data from the Department of Health (DOH), 400,000 hospital beds are needed to meet the population need for hospital care (or about 2.7 beds per 1,000 population).

About half of Filipinos do not have timely access to primary healthcare facilities. In 2020, only 50 percent of Filipinos were able to access primary health care within the standard time frame set by the government, which is 30 minutes.

Ulep and Casas added that public health spending in the Philippines is one of the lowest in the ASEAN region.

A World Health Organization (WHO) report showed that the country spends only about 1.5 percent of its gross domestic product on health, which is significantly lower than that of Thailand, Viet Nam, Singapore, and Malaysia.

The country also lacks health human resources. Based on DOH’s health facility survey in 2019, only 90 percent of rural health units or primary healthcare facilities have at least one medical doctor, while a significant number of health facilities do not have a nurse or a midwife.

In terms of preparedness for public health emergencies, the Philippines received an average score of 53 percent from WHO’s International Health Regulations (IHR), making it one of the poorest performing countries in the region next to Lao PDR and Cambodia. The IHR monitors the capabilities of a country’s health system to detect, assess, and notify public health risks and emergencies of national and international interest, including pandemics.

To address these challenges, Ulep and Casas provided some recommendations.

One is for the government to attract domestic and foreign investments to finance and close the country’s health infrastructure gap in the medium and long term. This can be done by increasing the equity threshold for hospital foreign investments to 100 percent, imposing additional tax breaks for hospital investments, and accelerating investment approvals for health services and medical equipment, among others.

They also urged the government to develop and implement a well-thought-out medical tourism program that could bring in revenues to finance the universal health care program.

The government should also adopt digital reforms in providing health services. Ulep and Casas urged Congress to support the eHealth Systems and Services Bill to serve as the regulatory framework and to institutionalize telemedicine domestically, especially during the pandemic.

“This should be supported by comprehensive clinical practice guidelines, especially in the practice of teleconsultations,” they said.

They also suggested ways to facilitate the mainstreaming of digital health like providing capacity-building activities for medical workers and their administrative staff, incorporating telemedicine in medical education and training curricula, and giving certificates for telemedicine practice in continuing professional development.

Ulep and Casas also stressed the need to implement robust domestic reforms to liberalize the country for cross-border health integration.

“Pushing for regional health integration will be relevant to the country’s pursuit of universal health care, and openness to regional integration may be a way for the domestic system to be resilient in facing disasters (e.g., pandemics) and to foster effective health crisis management and achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3, which is to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all and at all ages,” they said. ###

This article is based on the PIDS Discussion Paper titled “Regional Health Integration and Cooperation in the Philippines”.