MANILA, Philippines — With only four days left until Election Day, some of the country’s top statisticians find themselves at loggerheads and pondering questions on whether survey designs need to be updated to more accurately reflect public sentiment in light of survey results that indicate a victory for Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

Statistics experts like Romulo Virola, former secretary-general of the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB), and Dr. Peter Cayton of the University of the Philippines, believe that the recent Pulse Asia surveys showing Marcos way ahead of his closest rival, Vice President Leni Robredo, had under- and overrepresented certain sectors.

Both believe that those in Classes A and B as well as the 18-41 age group were underrepresented, while there was an overrepresentation of those in Classes D and E. Virola also believes there was underrepresentation of those who reached college.

Cayton said that over- or underrepresentation meant that the “proportion of sample agents from a survey may be higher or lower than what is typically expected from a larger population.”

Virola clarified that he did not think Pulse Asia used a wrong sampling method, but that the over- and underrepresentation was the result of its post-stratification process, which focused on regional stratifications over sociodemographic group (SDG) profiles.

He noted that several studies and polls abroad have shown that age, class, and educational attainment have stronger impacts on voter preferences.

‘Flaws’

Virola tried to work out these “flaws” and reweighed the results of the March 16-21, 2022, Pulse Asia survey showing a 56-24 gap between Marcos and Robredo.

He did this by using the 2017 socioeconomic classification system (1SEC) developed by the UP School of Statistics (to adjust underrepresentation of the ABC classes); the distribution of educational attainment of the voting age population from the Philippine Statistics Authority (to adjust underrepresentation of those who reached college); and using the Comelec data on registered voters by age to adjust underrepresentation of the young voters.

Since the numbers barely moved from the March to the April 16-21, 2022, survey and Pulse Asia did not change its methodology from the first poll, “whatever the problem was from the very beginning was still there,” Virola told the Inquirer.

He admitted, however, that his computations were based on an “arbitrary” sharing of votes (60-40 in favor of Robredo) based on the assumption that there were relatively more Robredo supporters among the youth as well as those with higher educational and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Massive rallies

These assumptions, he said, were based partly on Google Trends data showing massive interest for Robredo. “Even though these are arbitrary metrics, I don’t think these are unreasonable given what is happening on the ground,” he said, referring to Robredo’s massive rallies.

His computations show that Marcos will still lead even after adjusting the nationwide count by socioeconomic class (53.7 percent versus 29.3 percent) and educational attainment (48.8 percent versus 31.2 percent).

However, adjusting the vote among those aged 18-41 and 42-57 shows Robredo taking over the lead narrowly with 40.4 percent to 39.6 percent.

Virola’s computations sought to augment the gaps in Pulse Asia’s sampling. But there are clashing opinions on whether over- or undersampling has significant implications on the research design.

Cayton said it could mean “some inherent deviation, at the very least.”

“If a group is under and overrepresented, the estimates tend to be a little more deviant in the way that it favors the overrepresented group than the underrepresented group,” he said. “If the deviation is very large, that might affect the outcomes in terms of whether it could be reliable and accurate.”

Cayton also tried to do ensemble methodologies that merged Pulse Asia survey and Google Trends data under the assumption that big data could also be a reliable metric of public sentiment.

His computations also bring Marcos and Robredo to a statistical tie. But he is also the first to admit that “there are a lot of heavy assumptions under this model.”

Men Sta. Ana, coordinator for the think tank Action for Economic Reforms, said the sampling used by Pulse Asia was “close to the true distribution,” especially since the demographic description of the respondents emerged only after conducting the random survey.

“Random variation is not a systematic bias. It just happens precisely because the result stems from randomness,” he said. A well-designed random survey “will result in a random variation that is insignificant,” he added.

Even without members from Classes A and B—who are notoriously difficult to interview and belong to the top 1 percent of households—in the mix, the variance would remain very small, Sta. Ana said.

Never compromised

Pulse Asia defended its methodology, which it had used for decades.

The margin of error for each SDG reflected the “variance for the SDG,” given its share of the total sample of the survey. It also corrected, “to a significant extent, what Dr. Virola finds as an under/oversampling of specific SDGs,” Pulse Asia president Ronald Holmes said in a statement.

He rejected claims that Pulse Asia had been “bought” and its work compromised. Creating such doubts on scientific polls “only deepen polarization and distrust and contribute to the continued erosion of an already extremely feeble democratic order,” Holmes said.

“Those who make these unfair and unjust criticisms bear the responsibility for their baseless accusations feeding into the spiral of disinformation and malinformation that affects our society,” he said.

Based on location

Research companies, like Pulse Asia, use multistage probability sampling based on location. Thus, the data on socioeconomic classes come after the survey when respondents are grouped into classes.

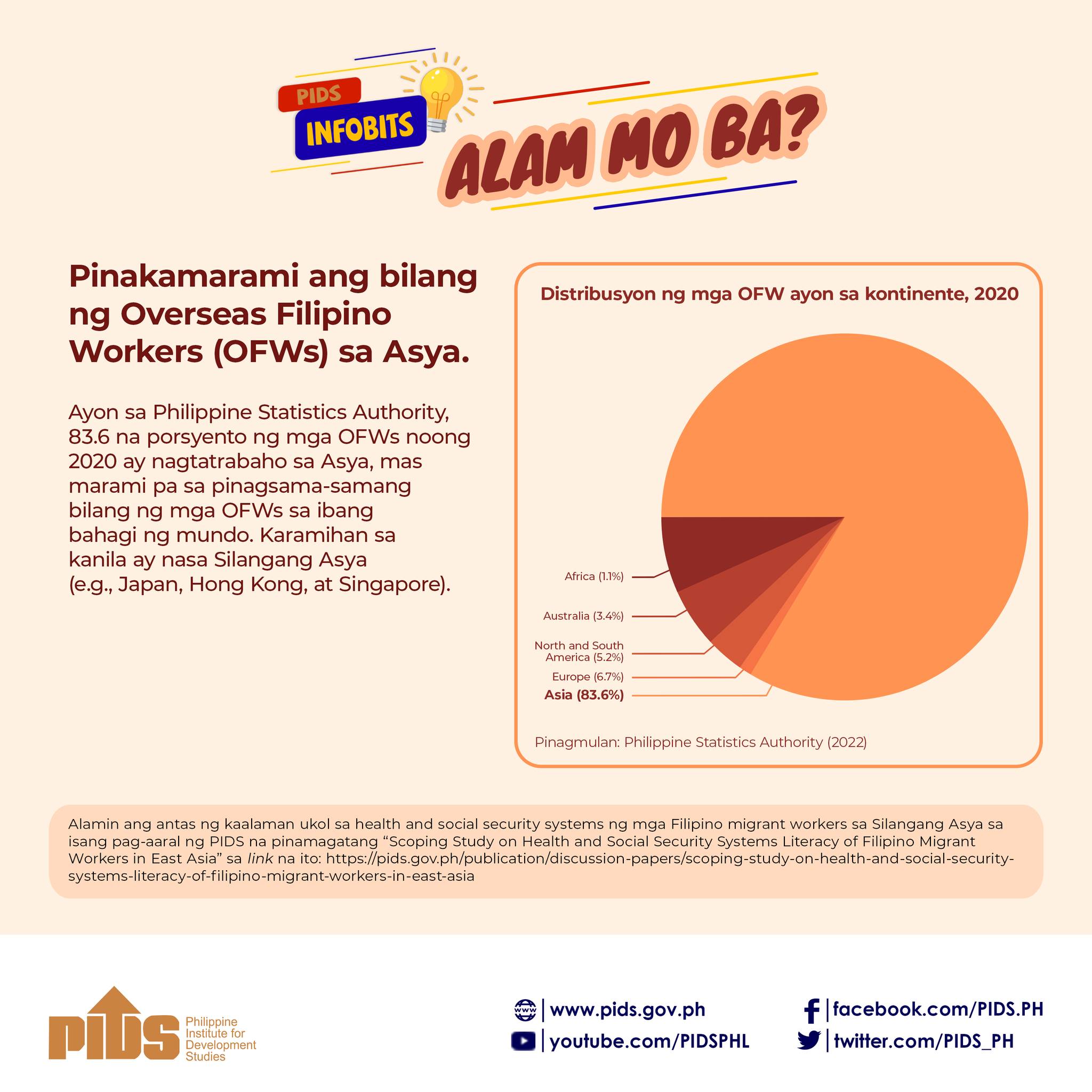

According to Jose Ramon Albert, a senior research fellow at the state-owned think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), it is impossible to sample households across socioeconomic and income groups as no one has a complete listing.

“Pulse Asia and SWS (Social Weather Stations) tables that list [socioeconomic status] are ‘afterthoughts’ from data collected in the survey, just as the tables on [PIDS] income groups. They are themselves data from the surveys,” Albert said.

Google appropriately warns that information available on its search trends page is not a substitute for polling data as users may want to know more about a party or politician for any number of reasons, without intending to vote for them.

Surveys and online trends reflect public preference and interest at the time the survey was taken or data was collected but people can and do change their minds up to the day of the elections.

After the 2016 presidential elections, the exit polls of SWS showed that voters decided on their choice for president a little later: 18 percent of those interviewed said they made their choice only on Election Day itself; another 15 percent decided only during the period May 1 to 8; 12 percent made their decision in April; 8 percent in March; and 46 percent in February or earlier.