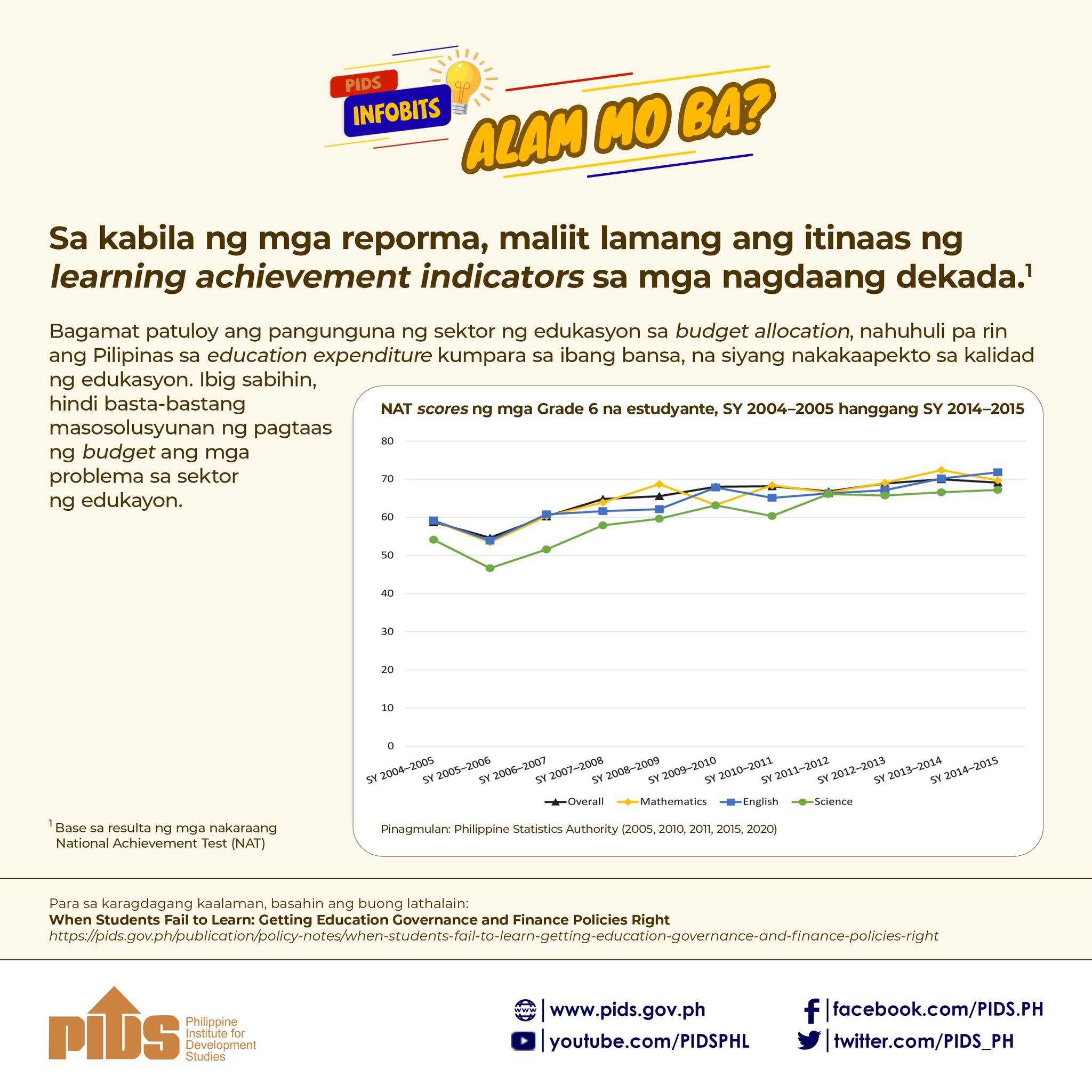

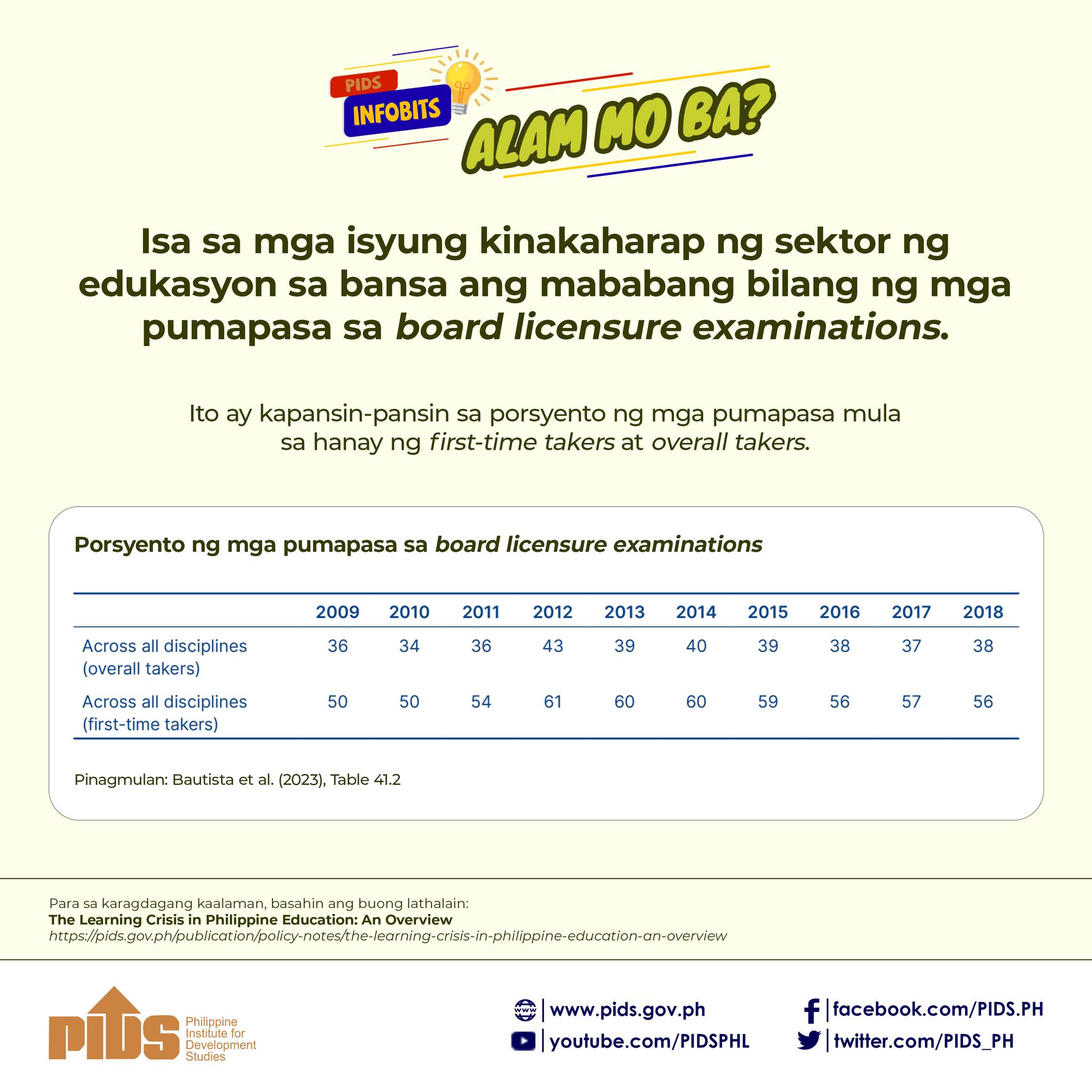

School closures during the first wave of COVID-19 lockdowns inflicted significant learning losses on students.

Younger students and those from disadvantaged backgrounds are experiencing the greatest setbacks, compromising their educational trajectory and future opportunities.

This was according to World Bank Senior Adviser for Education Harry Patrinos who presented his study findings during a knowledge-sharing session at the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS). His study highlighted that the longer schools remained closed, the greater the learning loss.

“For every week of closure, learning levels decline by almost 1 percent,” Patrinos said. “Twenty weeks closed translates to losing almost a year’s worth of learning,” he explained.

Surprisingly, the study found that factors such as income, school quality, Internet access, existence of private schools, or the severity of the COVID-19 outbreak itself, had no significant impact on learning losses. The sole significant determining factor was the duration of school closures.

“Policymakers thought that the [education] system was strong enough to withstand school closures,” Patrinos observed. He noted that lockdown stringency likely played a significant role. When lockdowns are widespread and strictly enforced, school closures become less of a choice. Additionally, national income and vaccination rates influenced closure duration, with higher income and faster vaccination rates leading to shorter school closures.

To confirm these findings and assess global impact, Patrinos further analyzed the data from international assessments like the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). According to him, both PEARLS and PISA estimate similar income and productivity losses, underlining the pandemic’s significant impact on educational achievement and future economic potential.

The long-term consequences of these losses are concerning, potentially translating to reduced human capital development and future earnings. Estimates suggest global losses of USD 15 to 21 trillion and an 8 percent annual GDP decrease. Younger and disadvantaged students are expected to be hit the hardest, exacerbating existing inequalities.

Locally, a concurrent PIDS study by PIDS President Aniceto Orbeta Jr. titled “Basic Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Do Enrollment by Learning Modality and Household Characteristics Tell Us?” (https://pidswebs.pids.gov.ph/CDN/document/pidsbk2022-covid19.pdf) presents a complementary perspective. The study identifies two key factors disproportionately affecting lower socioeconomic classes: lack of quality home support and less conducive learning environments. These findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions to bridge identified gaps and create equitable learning opportunities for all students.

Patrinos highlighted the crucial need to prioritize education, particularly for vulnerable groups. Urgent interventions are needed to address learning loss and associated costs, including direct support like tutoring and extended school hours, alongside protecting education budgets, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Preparing for future disruptions by investing in resilient education systems and measuring learning outcomes are also crucial.

“We need to improve on what we do on [national] assessment and make that [data] available for teachers and policymakers,” he emphasized. According to him, this strategy is essential for monitoring progress, identifying vulnerable groups, and tailoring interventions.