The Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) is getting flak for its apparent inability to solve widespread poverty, which is quite weird because it was never meant to do so.

The Commission on Audit (COA) had recently recommended a comprehensive review of the efficiency of this government program. This is pursuant to its findings that about 3.82 million or 90% of the 4.26 million household beneficiaries are still below the poverty level, despite being covered by the program for, at most, 13 years.

Yesterday, Sen. Imee Marcos floated the idea of coming up with an exit strategy to discontinue the 4Ps, noting that only 900,000 students under the program had graduated since its introduction 15 years ago. This was supported by Sen. Win Gatchalian, who stressed that beneficiary families seem to remain poor despite their children’s higher participation in school.

But such recommendations may be off the mark. Considering that the 4Ps were introduced to solve very specific problems, measuring its success based on such vague parameters within a very narrow period might not be fair, especially for indigent families relying on the program to survive the rising costs of food, fuel, and other basic necessities.

Minding the target

Introduced under the Aquino administration, the 4Ps was an expansion of the Arroyo adminstration’s Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) program first implemented in 2008. Under the Arroyo CCT program, indigent families were given a cash grant of P500 per month for health and nutrition purposes and an additional P300 for education expenses. The Aquino 4Ps expanded this program while adding specific conditions. The 4Ps required beneficiaries to avail of prenatal and postnatal care for pregnant women, to attend family development sessions and seminars, to have infant children vaccinated, and to enroll children 3 to 18 in school, maintaining an attendance of at least 85% of class days every month.

Since there are clear established outcomes the program sets out to achieve, measuring its efficacy based on the capability of families to rise above the poverty level may be misguided. It disregards that in terms of its established goals, the program has been quite effective.

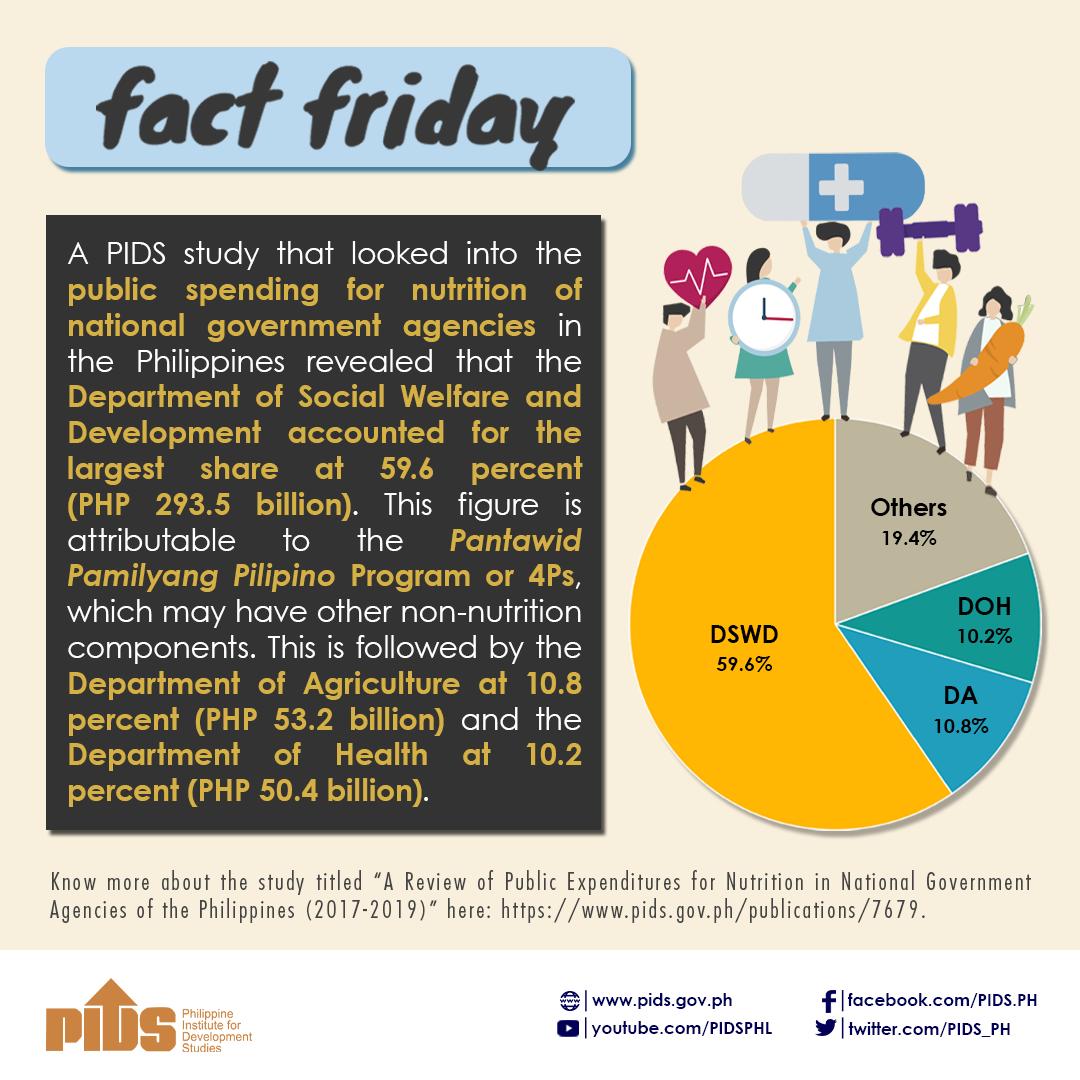

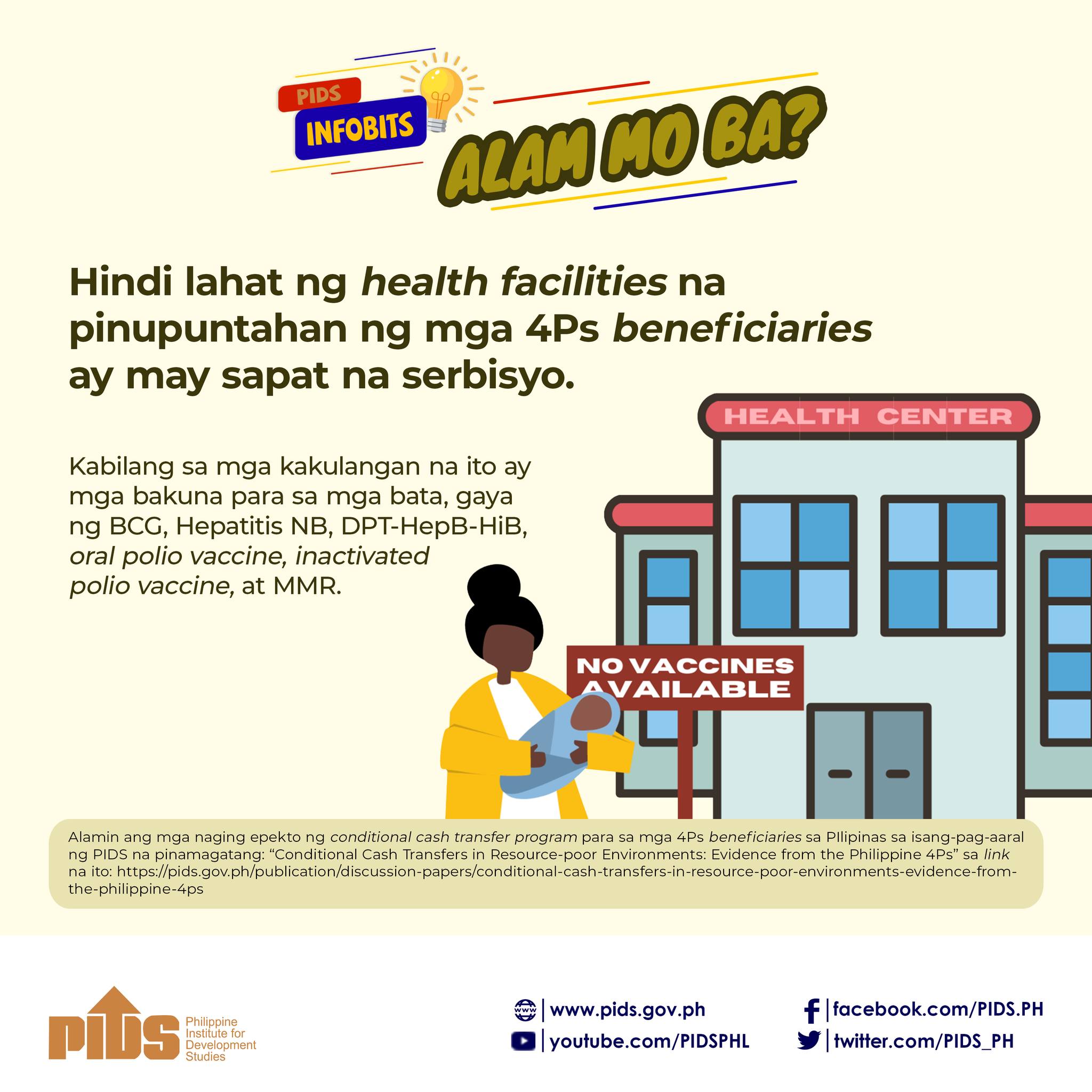

According to a study released by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies last February 2021, the 4Ps showed “desirable impacts on most of the target education and health outcomes of children and pregnant women,” namely “positive impacts on household welfare such as income and food security; large positive impacts on community participation; and awareness of basic means to mitigate vulnerabilities such as disaster preparedness among adults.” The 4Ps also showed a strong impact on the “grit” or determination of children to pursue their studies.

Experts: 4Ps need to be improved, not gutted

What is curious is that the current calls for a “strategic exit” from the 4Ps is actually contrary to the recommendations of policy experts, considering that the implementation of the 4Ps are actually not at par with best practices by countries with similar CCT programs.

Last November 2021, PIDS reported in its “Evaluating the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program’s Payment System” that the amounts of the cash transfers “have remained at their nominal levels from 2008 to 2016, even though their real value has already decreased due to inflation,” with significant increases only happening in 2017 and 2020. Compared to other CCT programs from other countries, “the generosity of the [4Ps] program is actually [at] the bottom 20 %.”

The recommendation by the government think tank is actually to improve the responsiveness of the 4Ps to price fluctuations by “establishing a principle for adjusting the grant amount” and by “the importance of reliability and predictability of payment schedules.” The February 2021 study also recommended strengthening project monitoring and enforcement of health-related conditions.

Death to 4Ps? Not today

CCTs under the Arroyo administration were introduced in 2008 as a response to a food crisis. Under the Aquino administration, it was expanded to meet Sustainable Development Goals on reproductive health, primary education, and child nutrition. In each iteration, CCTs have very specific goals which can help alleviate poverty. But it is misguided to measure it based on whether it has done the latter, especially if it is meeting the former.

How the senators and other policymakers are framing the issue reveals an important facet regarding the 4Ps: that even among legislators and implementers, there is a disconnect between the goal and the program. They went along with CCTs convinced that it would solve poverty, only to find that it didn’t. And now, they may push for its removal, ignoring the benefits that it did achieve.

Gutting social welfare programs will not help poverty alleviation, especially when the real value of wages are falling while the cost of living keeps rising – and especially under the shadow of the pandemic, where dropout rates among the student population have increased significantly. There may come a day when the impoverished would no longer need social safety nets like the 4Ps. But it is not today.

Policymakers are right that there is a need to end poverty. Yet it will not be helped by removing social welfare programs. Especially ones which have been proven to work.