The next administration will inherit a social time bomb — this social timebomb is income inequality, or the gaps in the distribution of wealth among members of a population.

Economists gauge income inequality through a mathematical expression called the GINI Coefficient. The GINI Coefficient is a number between zero and one (or 100%), zero being a population where wealth is perfectly distributed (everyone makes the same income) and one where inequality is most acute (were one person has all the money and the rest have none). The higher the number, the higher the inequality.

As usual, the Philippines has the highest GINI coefficient among ASEAN’s six largest economies at 41.58%. Malaysia follows at 39.37%, Indonesia is at 38.33%, Vietnam is at 35.58%, Singapore is at 35.58%, and Thailand’s is 34.55%. For context, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, and Iceland are the world leaders in as far as income equality is concerned, with GINI coefficients between 24% and 26%. South Africa is the most inequitable with a GINI coefficient of 63% due to the after-effects of apartheid.

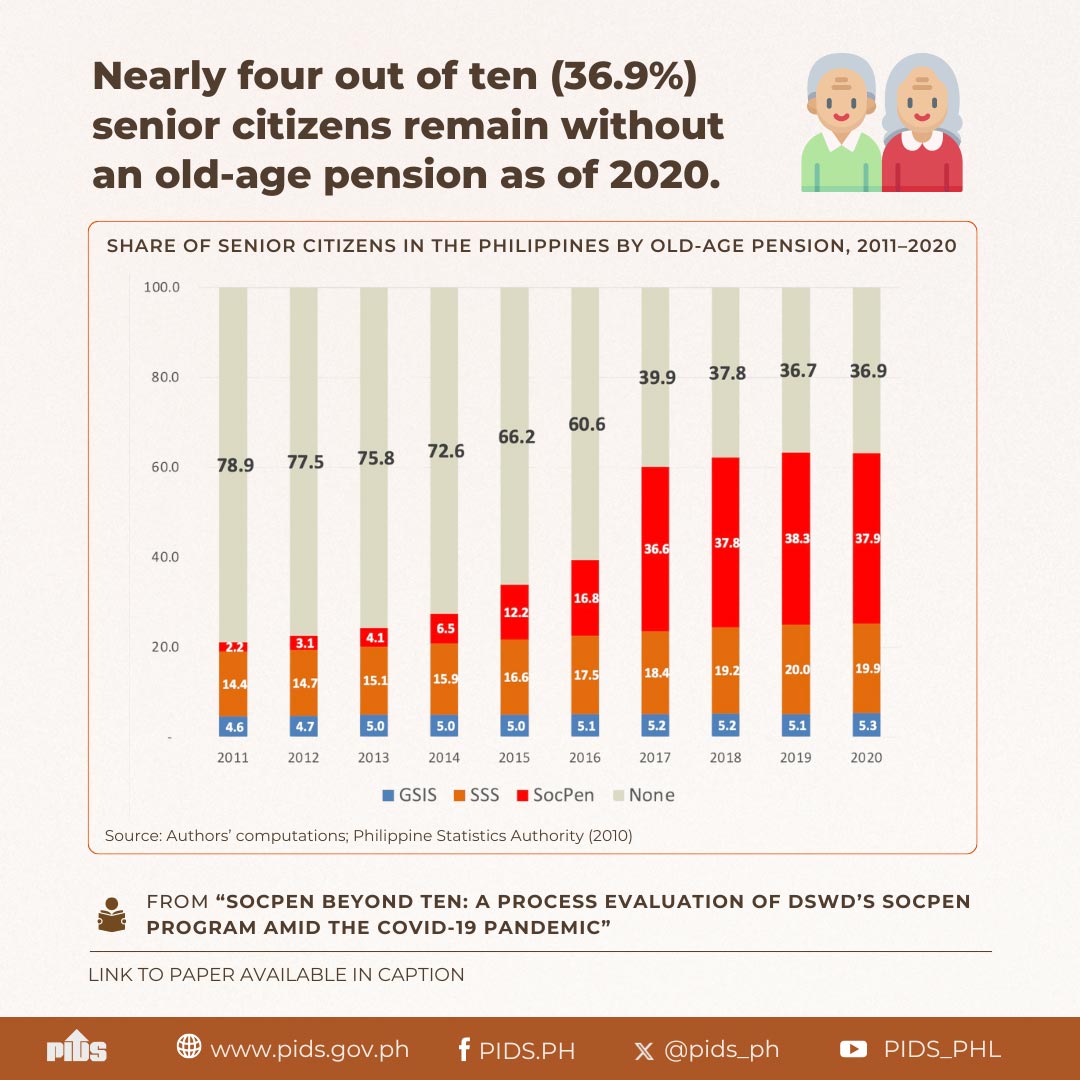

The Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) published a report to determine the distribution of wealth in the Philippines. With the poverty line being a household income of P10,481 per month for a family of five, PIDS reported that 22% of Filipino households are presently living below the poverty line. Households earning between P10,481 to P20,962 are considered the low-income class and they constitute 35% of the population. Together, these two classes constitute 57% of the population.

The lower and upper middle class earns between P20,962 to P125,772 per month and they make up 40% of the population. Households that earn between P125,772 and P209,620 are considered upper class and they comprise 2% of the population. Less than 1%, or some 143,000 families, are considered rich with a monthly income of P209,620 or more.

Why is income inequality a social timebomb?

It is a social timebomb for multiple reasons, the most significant of which is social tension. In a society like ours where the poor constitute 57% of the population, government channels the lion’s share of its support towards this sector, be it through financial amelioration, free education, healthcare and housing. The middle class is crowded-out and deprived of such social safety nets. The middle class is where discontent is greatest and tension is highest. History shows that in most societies with acute income inequality, the call for social change through revolutions are instigated by the middle class.

Other consequences of acute income inequality include low average education levels, low technology adoption, poor public health, high crime rates, and high dependence on state subsidies. All these translate to lower labor productivity, lower long term GDP growth rates, and a heavy public welfare burden.

How do we diffuse the tension? There is no other way but to make the distribution of wealth more equitable. The good news is that it can be done with relative ease with the implementation of the right policies.

Before we dive into the policies, however, let us first look at the three sectors of the economy — agriculture, services, and industry. The agricultural sector employs 22.86% of the workforce but the average income of its workers is only P9,930 per month. It is below the poverty line. This indicates that the greater majority of our agricultural workers are engaged in subsistence farming. The service sector is where 58.03% of our workforce derive their livelihood. Each worker has an average income of P16,754 a month, or slightly above minimum wage. The industrial sector is where the least number of the workforce are employed at 19.12%. However, it is also the sector where average income is highest at P26,019 per month.

To improve income inequality, we must migrate as many subsistence farmers and minimum wage earners to the industrial sector as possible. To do this, we must shift policies from Dutertenomics (the propagation of a consumer-lead economy, pump-primed with massive government spending, financed by debt) and embrace rapid industrialization.

Only with the development of industry can we push wages higher with more of the workforce employed in factories. As we have illustrated, the industrial sector offers higher wages, along with security of tenure and health/housing benefits.

To avoid any misunderstanding, this is not to say that we should abandon the agricultural and service sectors. Both should be developed but made to climb the value chain. Agriculture, especially, must be mechanically and technologically enabled for wages to rise in tandem with industry.

I recommend a five-point plan to facilitate the migration of subsistence farmers and low-income service providers to higher paying jobs in the industrial sector.

First, relaunch the Manufacturing Resurgence Program (MRP). This would mean reviving, updating, and pursuing the 60+ industry roadmaps made by the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) in 2013 to realize the full potentials of existing industries. For waning industries like leather goods and garments, it would mean resolving the impediments that have stunted their growth. For thriving industries like electronics and IT-KPO, it would mean climbing the value chain of technology and securing a larger share of the global market.

Second, diversify the economy from one that is a competent producer of only 500 products today to 2,000 products (the Asian average). This recommendation deserves a separate piece on its own due its complexity – suffice it to say that we must first establish base industries (e.g., metal, petrochemicals, textiles, petroleum, precision machines, glass and lenses, rubber, etc.) as these are fundamental for a strong manufacturing sector.

Third, we must fast track the development of new industries for which the Philippines has a competitive advantage. These include maritime-related industries, IT-KPO, electronics, electric vehicles and parts, mining, mechanized agro-processing, aeronautics and aerospace, construction, creative industries, E-commerce and data hubs.

Fourth, there is no way out of it, we must secure our fair share of foreign direct investment (FDI). Between 2015 and 2021, the Philippine’s share of FDI was only 5.89% of all FDIs that poured into the ASEAN. We can do better. We must open up the economy more, especially the 60-40 equity restrictions; improve ease in doing business; fix the inconsistent and unpredictable treatment of investors by the tax authorities, especially in VAT refunds; accelerate infrastructure development, especially those that affect manufacturing logistics chains; improve workforce training and capacitation; outlaw discretionary aspects of administrative rules, especially in granting government licenses, permits and franchises; and strengthen the justice system.

Fifth, still on FDI, we must intensify our outbound investment missions with a deliberate intention to fill our supply chain gaps. To accomplish this, I recommend the establishment of the Office of Strategic Investments Promotions and Economic Coordination (OSIPEC), which is patterned after InvestVietnam. Not to be confused with the Board of Investments, the OSIPEC is proposed to be under the office of the president. Its core function will be to undertake non-stop outbound investment missions, provide investor concierge services for ease in entry, and liaise between government agencies and foreign investors. The OSIPEC will cooperate with the DTI in industrial planning and aggressively court strategic investors to fill supply chain gaps.

The faster we undertake the five-point plan, the faster we industrialize. The faster we industrialize, the faster we distribute wealth and achieve greater income inequality.