Policymakers should push for an integrated approach to urban environment resilience.

Dr. Marife Ballesteros, acting vice president of state think tank Philippine Institute of Development Studies (PIDS), in her presentation at the Second Annual Public Policy Conference on Risks, Shocks, Building Resilience, recently said a clear understanding of the nature of resilience must first be addressed before policy recommendations can be made.

“Risks are complex, but so is resilience,” said Ballesteros.

In order to target urban resilience specifically, studies should focus on the metropolitan areas, such as Manila, where urban environment problems are “most glaring, she added.

A panelist also raised the need for an integration of disciplines, where social sciences must be combined with the natural sciences to maximize their strengths in crafting policy solutions.

“We are so trained as specialists, economists, political scientists, physicists, but the reality is that the problems we are facing are all interconnected,” said Dr. Emma Porio, sociology professor from the Ateneo de Manila University who discussed risk and resilience in Metro Manila during the session.

“In a sense, when you think of urban resilience in the city, you have to think of the city as a system,” she added.

Porio explained policymakers should look at the interaction of the geophysical, political, economic and social aspects so as to understand vulnerability and the potentials of building resilience in Metro Manila.

Gilberto Llanto, PIDS president, earlier urged policy makers to look beyond natural hazards and acknowledge that the sources of risks are many and that those risks are interconnected.

Porio also challenged the current manner of looking at the socioecological and political development in governance in understanding urban environment.

“Floods do not recognize political boundaries, but we always make planning and data analysis according to political administrative boundaries,” she said.

Ballesteros noted that the Philippines still has a lot to do in terms of building resilience.

“There is a significant policy gap in terms of structures, laws, and mindsets,” Ballesteros said.

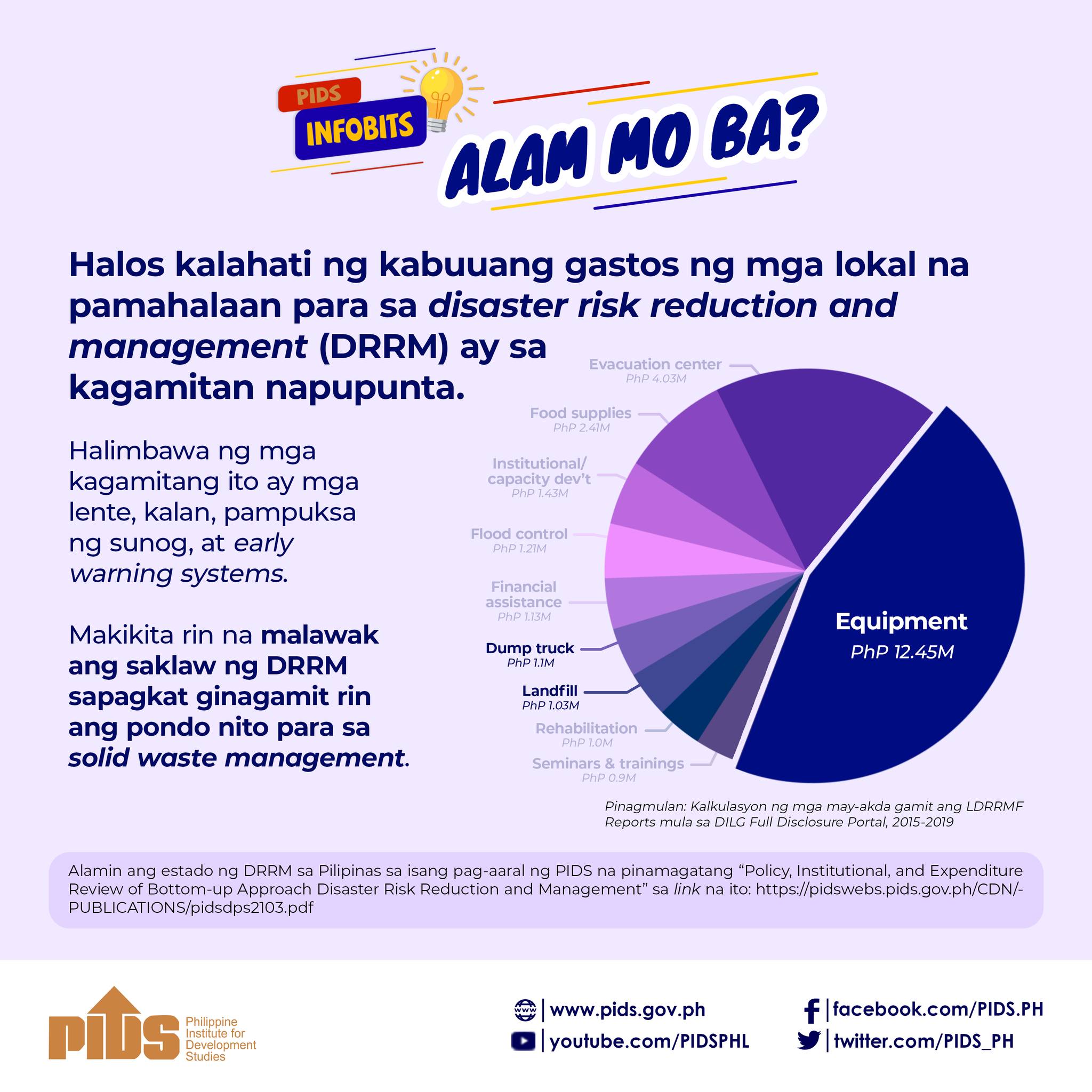

A review of Republic Act 10121 or the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010 is not adequate, Ballesteros said.

Porio added that the present governance system only reacts to the current needs of this generation.

“It does not think whether your grandchildren will have resources in the future,” she said.

In terms of climate adaptation, Porio said the government should come up with convergent and integrative ways of addressing the issue. “Right now, what we have is a fragmented system of governance at different levels,” she added.

Porio explained that “our policymakers continue to put ourselves in an increasingly risky situation because of their decisions.”

Manila is considered the most exposed city to natural disasters in the world, according to the 2016 Natural Hazards Vulnerability Index from the United Kingdom-based risk analyst, Verisk Maplecroft.

Dr. Marife Ballesteros, acting vice president of state think tank Philippine Institute of Development Studies (PIDS), in her presentation at the Second Annual Public Policy Conference on Risks, Shocks, Building Resilience, recently said a clear understanding of the nature of resilience must first be addressed before policy recommendations can be made.

“Risks are complex, but so is resilience,” said Ballesteros.

In order to target urban resilience specifically, studies should focus on the metropolitan areas, such as Manila, where urban environment problems are “most glaring, she added.

A panelist also raised the need for an integration of disciplines, where social sciences must be combined with the natural sciences to maximize their strengths in crafting policy solutions.

“We are so trained as specialists, economists, political scientists, physicists, but the reality is that the problems we are facing are all interconnected,” said Dr. Emma Porio, sociology professor from the Ateneo de Manila University who discussed risk and resilience in Metro Manila during the session.

“In a sense, when you think of urban resilience in the city, you have to think of the city as a system,” she added.

Porio explained policymakers should look at the interaction of the geophysical, political, economic and social aspects so as to understand vulnerability and the potentials of building resilience in Metro Manila.

Gilberto Llanto, PIDS president, earlier urged policy makers to look beyond natural hazards and acknowledge that the sources of risks are many and that those risks are interconnected.

Porio also challenged the current manner of looking at the socioecological and political development in governance in understanding urban environment.

“Floods do not recognize political boundaries, but we always make planning and data analysis according to political administrative boundaries,” she said.

Ballesteros noted that the Philippines still has a lot to do in terms of building resilience.

“There is a significant policy gap in terms of structures, laws, and mindsets,” Ballesteros said.

A review of Republic Act 10121 or the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010 is not adequate, Ballesteros said.

Porio added that the present governance system only reacts to the current needs of this generation.

“It does not think whether your grandchildren will have resources in the future,” she said.

In terms of climate adaptation, Porio said the government should come up with convergent and integrative ways of addressing the issue. “Right now, what we have is a fragmented system of governance at different levels,” she added.

Porio explained that “our policymakers continue to put ourselves in an increasingly risky situation because of their decisions.”

Manila is considered the most exposed city to natural disasters in the world, according to the 2016 Natural Hazards Vulnerability Index from the United Kingdom-based risk analyst, Verisk Maplecroft.