MANILA, Philippines – Poverty and disasters. What image do you see? Now try to picture the children caught in between.

The Philippines has reaped international praise for being Asia’s second fastest growing economy, next only to China. Critics, however, question whether all Filipinos benefit from this growth. Self-rated poverty reports and nutrition surveys reveal those who seem to have been left behind.

"Children in the Philippines are at more at risk than those in countries with less poverty,” said Carin van der Hor, Country Director of Plan International Philippines, a non-governmental organization (NGO).

As of 2012, Filipino children had a poverty incidence of 35.2% which is the 3rd highest among all basic sectors, next to fishers and farmers. This has remained unchanged in the past 6 years. In 2009, there were around 13.4 million poor children deprived of food, shelter, and education, the Philippine Institute for Development Studies reported.

Van der Hor cited a UN study stating that if the Philippines and Japan were to be hit by the same cyclone, the latter would have a mortality rate 17% lower than the Philippines. "Poverty plays a big part in this unacceptable discrepancy,” she added.

Children, Disasters

Super typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) affected over 5.9 million children in the Eastern Visayas. Many of them lost their homes, schools, and some also lost their families and friends.

"I will never forget a picture a 7-year-old girl drew. It showed destroyed houses, schools, coconut trees. And dead bodies,” recalled Richard Sandison, Plan’s Yolanda response manager.

Sandison, who has been in Tacloban since November 2013, stressed that poverty is not only about income, but also about unequal access to basic needs like water and sanitation, health services, information, opportunities, and emotional support. "This is social poverty.”

Among Yolanda-affected areas, Plan has set up 100 "child-friendly spaces” for over 20,000 kids. These are spaces where children can safely learn, play, and communicate. Counselling and psychosocial services are also available.

"Interestingly, we found that a lot of youth are asking about sex,” Van der Hor shared. "So we have classes too on reproductive health; this is important since rising cases ofteenage pregnancy are also a problem.”

Child trafficking is another issue to be closely monitored post-disasters, according to Plan. In some communities, Plan observed cases of child abuse among girls below 14 years old.

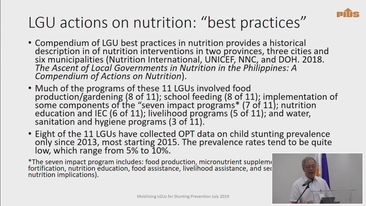

Poor nutrition is another concern. "The biggest problem we see is stunting, but this is not a direct effect of Yolanda, they were already malnourished even before,” Sandison clarified. Malnourished children, however, are more vulnerable to communicable diseases common among unsanitary and crowded environments post-disasters.

To address such issues, Plan – alongside other NGOs and local governments – provides climate-resilient model shelters, water and shelter kits, cash-for-work assistance, and health classes to affected families. Plan carried out a blanket food distribution from November to February, and has since then focused on more targeted communities.

Sandison advised other groups doing supplementary feeding programs to use locally available vegetables. "Feeding programs are not enough, what’s more important is to educate parents on proper nutrition,” he argued.

And if the parents themselves are unhealthy, how can they take care of their children?

‘Voice’

Plan highlights the need to hear the voices of the community before doing crafting programs or doing intervention.

"We want to build back better,” said Sandison, "We have to tap into the power of local communities. Involve them as partners in their recovery journey. We not only build back structures but also knowledge, community spirit, and resilience.”

The families themselves are encouraged to be part of the planning and evaluation process of all programs.

During consultations, Plan found out that many barangays were requesting for more disaster and risk reduction (DRR) training since many of them do not have any DRR plans at all.

Barangays can be trained to have their own emergency response teams.

"Children have their own voices, problem is we don’t listen,” Van der Hor added. She advised response groups to not speak in behalf of children, but to let the children speak for themselves.

In fact, Plan trained children to report on issues they want to highlight them, through its "Youth Reporter Project."

‘New normal’

Before being assigned in the Philippines, Sandison was part of the Aceh tsunami response team in Indonesia for two years. "After a year, there were still 100,000 people living in tents in Aceh. In the Yolanda context, it's also many but it’s less,” Sandison said.

Ideally, people should only stay in tents for up to 4 months, until they move into better transitional shelters. (READ: Families still in tents)

Plan lauded the Philippines for its "satisfactory” response and recovery efforts. "Was the recovery fast? Some parts yes, some no. Was it satisfactory? Yes. There was proper coordination,” Van der Hor said.

Van der Hor emphasized that Plan is not interested in criticizing the government; what is important is that action is being done. "We don’t care who likes who. We just want agencies to fulfil their mandates and for them to be accountable,” she added. (READ:'Why refuse us help?')

Plan hopes that the Philippines can introduce legislation protecting children in emergencies; a law that can provide children with better and continuous access to basic needs and social services.

"This is the new normal. Development that is inclusive, disaster and climate resilient, and ensures that that children are prepared for whatever comes their way, no matter how rich or poor they are,” Van der Hor said. – Rappler.com

October is National Children's Month. What are the most pressing issues faced by Filipino children and what can we do to help address them? Send your stories and ideas to move.ph@rappler.com