TO COMBAT emerging health issues such as COVID-19, including infectious and resurgent diseases such as polio, the Department of Health (DOH) should expand the employment and wages of healthcare and medical personnel in all public institutions.

Understaffing in our public hospitals and local health centers cannot persist in a time of COVID-19, measles and dengue, HIV epidemic, and prevalence of stunting. DOH should ask Congress to increase the budget for health personnel and necessary organizational requirements.

Sen. Risa Hontiveros recently called for a “community health surveillance system” which would monitor the health, nutrition and immunization of every person in every sitio, and identify people at risk due to exposure or malnutrition. But this system would require doctors, nurses, nutritionists, dentists, and pharmacists in every sitio, as well as medical technologists and epidemiologists in every municipality.

DOH should revise its workforce structure, regularize its existing work, and begin to hire more regular health personnel. While healthcare is technically devolved under the Local Government Code, it is the national government’s mandate to address health problems which cuts across local government units (LGUs) and which go beyond the manpower and budgetary capacity of local government. Congress is thus urged to quickly close the gap between DOH’s existing capacity and what is needed for 21st century health threats, even if it means tripling or quadrupling its current budget.

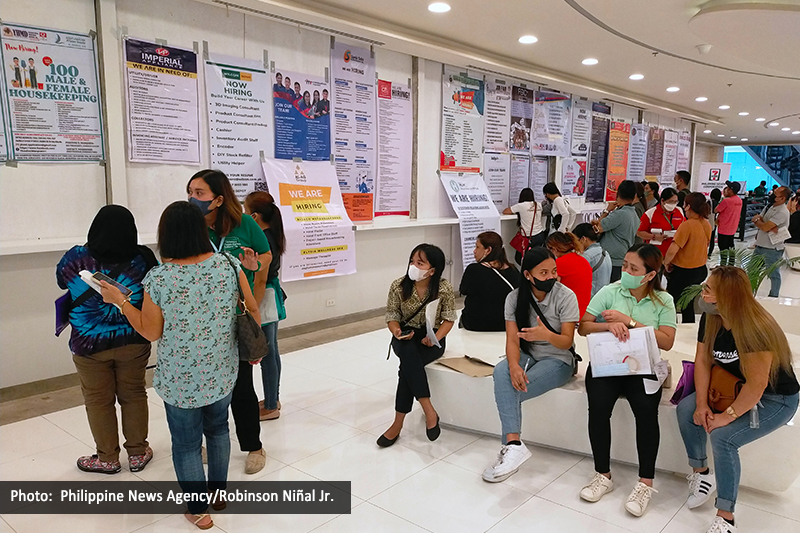

The 4th Graduate Tracer Study (GTS) from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) showed that while 21.6 percent of students surveyed took up nursing, only 52.8 percent of the nursing students were eventually matched to appropriate jobs. Of those unmatched, 11 percent eventually worked as contact center information clerks, eight percent went to retail and wholesale trade, and 9.7 percent either went on as general office clerks or cashier and ticket clerks.

This is unacceptable. We badly need nurses to run our healthcare units, but our nursing graduates don’t end up in nursing jobs. The waste of tertiary education resources during a time of healthcare crisis is a travesty of epic proportions. The urgency of increasing public health personnel, given the expected economic effects of diseases like COVID-19 which will likely hike unemployment figures, should not be taken lightly.

Understaffing in our public hospitals and local health centers cannot persist in a time of COVID-19, measles and dengue, HIV epidemic, and prevalence of stunting. DOH should ask Congress to increase the budget for health personnel and necessary organizational requirements.

Sen. Risa Hontiveros recently called for a “community health surveillance system” which would monitor the health, nutrition and immunization of every person in every sitio, and identify people at risk due to exposure or malnutrition. But this system would require doctors, nurses, nutritionists, dentists, and pharmacists in every sitio, as well as medical technologists and epidemiologists in every municipality.

DOH should revise its workforce structure, regularize its existing work, and begin to hire more regular health personnel. While healthcare is technically devolved under the Local Government Code, it is the national government’s mandate to address health problems which cuts across local government units (LGUs) and which go beyond the manpower and budgetary capacity of local government. Congress is thus urged to quickly close the gap between DOH’s existing capacity and what is needed for 21st century health threats, even if it means tripling or quadrupling its current budget.

The 4th Graduate Tracer Study (GTS) from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) showed that while 21.6 percent of students surveyed took up nursing, only 52.8 percent of the nursing students were eventually matched to appropriate jobs. Of those unmatched, 11 percent eventually worked as contact center information clerks, eight percent went to retail and wholesale trade, and 9.7 percent either went on as general office clerks or cashier and ticket clerks.

This is unacceptable. We badly need nurses to run our healthcare units, but our nursing graduates don’t end up in nursing jobs. The waste of tertiary education resources during a time of healthcare crisis is a travesty of epic proportions. The urgency of increasing public health personnel, given the expected economic effects of diseases like COVID-19 which will likely hike unemployment figures, should not be taken lightly.