GOVERNMENTS generally tend to implement a number of measures or programs to help those with short- or long-term financial or economic problems.

These include the provision of emergency health care (an example of this would be the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office providing financial aid to a beneficiary for his or her hospitalization); relief operations in the wake of a natural or man-made disaster, like a huge fire in a shanty area; the unemployment-benefit programs of some Western countries, which are designed to help people get through a tough period until they get back on their feet; and conditional cash-transfer (CCT) programs.

Each measure or program is designed to fulfill a specific need and hopes to lift its beneficiaries out of the awful circumstances they are in and put them on the path to a better (preferably middle-class) life, as well as to help in the fight against poverty. None of them are designed to make the beneficiaries feel more comfortable with their current condition.

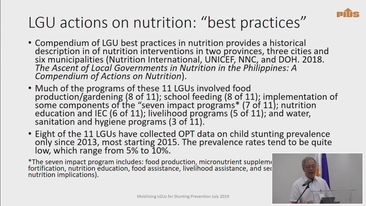

The Aquino administration’s CCT program, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), is designed with those goals in mind. The millions of poor families enrolled in this program are required to keep their school-age children in educational institutions. The 2014 budget for this program is P62 billion; approximately P105 billion has been spent since 2012.

No doubt the 4Ps has helped many poor households, but if its goals are for the long term, then there is a problem. Consider: Studies show that, in 2011, more boys (22 percent) than girls (8 percent) tended to drop out of school at 15 years old throughout the region. Sixty percent of 18-year-old boys were working instead of studying. The Philippine Institute for Development Studies has said school attendance among 4P families falls drastically as a child grows older, from 93 percent for those who are 13 to just 33 percent for those who are 18.

The success of the 4Ps should not be ignored. The program, however, is only the first step, and the country is waiting for the government to make the second step: genuinely prepare the beneficiaries–and others like them–for jobs.

Perhaps, part of the solution lies in the idea that the 4Ps should somehow be integrated into the existing training programs already implemented by the government. As the first step, the 4Ps is there to help our young people stay in school to receive their basic education. Once that’s accomplished, the obvious next step should be to provide them with job skills.

Meanwhile, the older 4Ps beneficiaries–the parents of these young people–might also want to start providing for their families. A joint private- and public-sector partnership, including additional and continuing financial incentives, would better keep the children’s education and jobs training going while offering a way for their parents to help contribute to their families’ well-being. Both short- and long-term goals must be addressed.