While prepandemic data suggested that six million Filipinos were lifted out of poverty over the past two years, more recent data suggest that the number of poor Filipinos could surge by about 1.5 million to 5.5 million from the last statistical baseline of 17.7 million in 2018.

According to a paper published by state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), “the number of poor Filipinos could rise by about 1.5 million from the baseline figures, if everyone’s income contract by 10 percent, even with the [Social Amelioration Program, or SAP] and [small business wage subsidies, or SBWS] in place.”

“Without SAP and SBWS, the number of poor would rise even by 5.5 million,” the PIDS said in the paper, titled “Poverty, the Middle Class, and Income Distribution amid COVID-19,” released last Tuesday before the dismal report on the country gross domestic product (GDP).

But even if the country’s P16-trillion odd economy shrank by around 9 percent in the first half of 2020, acting Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Karl Kendrick Chua hoped the increase in poverty would not be too difficult.

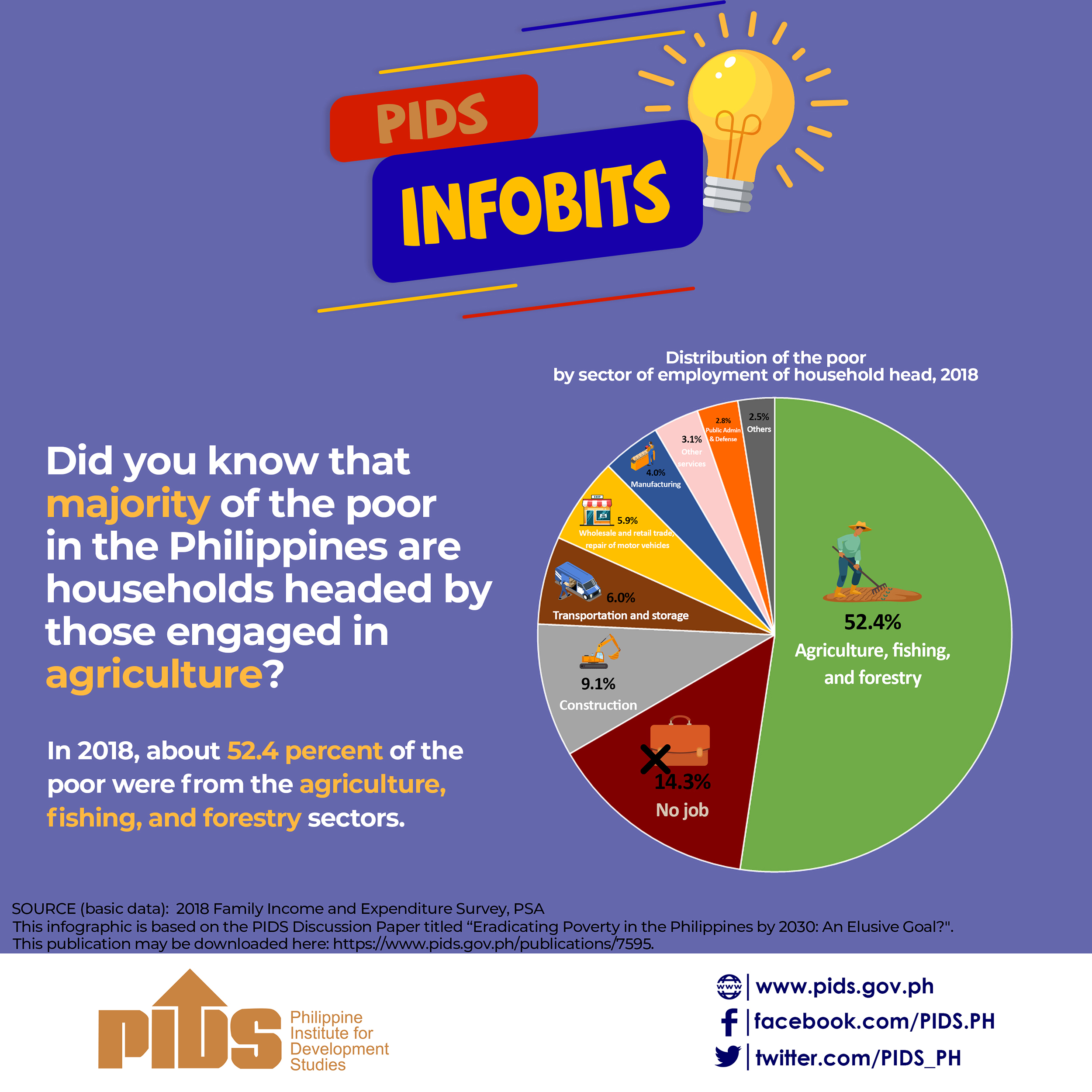

“Since most poor are rural and in agriculture, then the impact is less than in urban [areas], where the virus problem is more pronounced,” said Chua, who heads the state planning agency National Economic and Development Authority.

The “virus problem” caused alarming declines in the manufacturing, construction, and transportation and storage sectors, resulting in a record contraction of 16.5 percent in GDP in the second quarter.

But while the bulk of the economy shed trillions of pesos in output and millions of jobs at the height of the longest and strictest lockdown in the region, Chua noted that agriculture, forestry, and fishing managed to post a 1.6 percent growth in production.

According to a paper published by state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), “the number of poor Filipinos could rise by about 1.5 million from the baseline figures, if everyone’s income contract by 10 percent, even with the [Social Amelioration Program, or SAP] and [small business wage subsidies, or SBWS] in place.”

“Without SAP and SBWS, the number of poor would rise even by 5.5 million,” the PIDS said in the paper, titled “Poverty, the Middle Class, and Income Distribution amid COVID-19,” released last Tuesday before the dismal report on the country gross domestic product (GDP).

But even if the country’s P16-trillion odd economy shrank by around 9 percent in the first half of 2020, acting Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Karl Kendrick Chua hoped the increase in poverty would not be too difficult.

“Since most poor are rural and in agriculture, then the impact is less than in urban [areas], where the virus problem is more pronounced,” said Chua, who heads the state planning agency National Economic and Development Authority.

The “virus problem” caused alarming declines in the manufacturing, construction, and transportation and storage sectors, resulting in a record contraction of 16.5 percent in GDP in the second quarter.

But while the bulk of the economy shed trillions of pesos in output and millions of jobs at the height of the longest and strictest lockdown in the region, Chua noted that agriculture, forestry, and fishing managed to post a 1.6 percent growth in production.