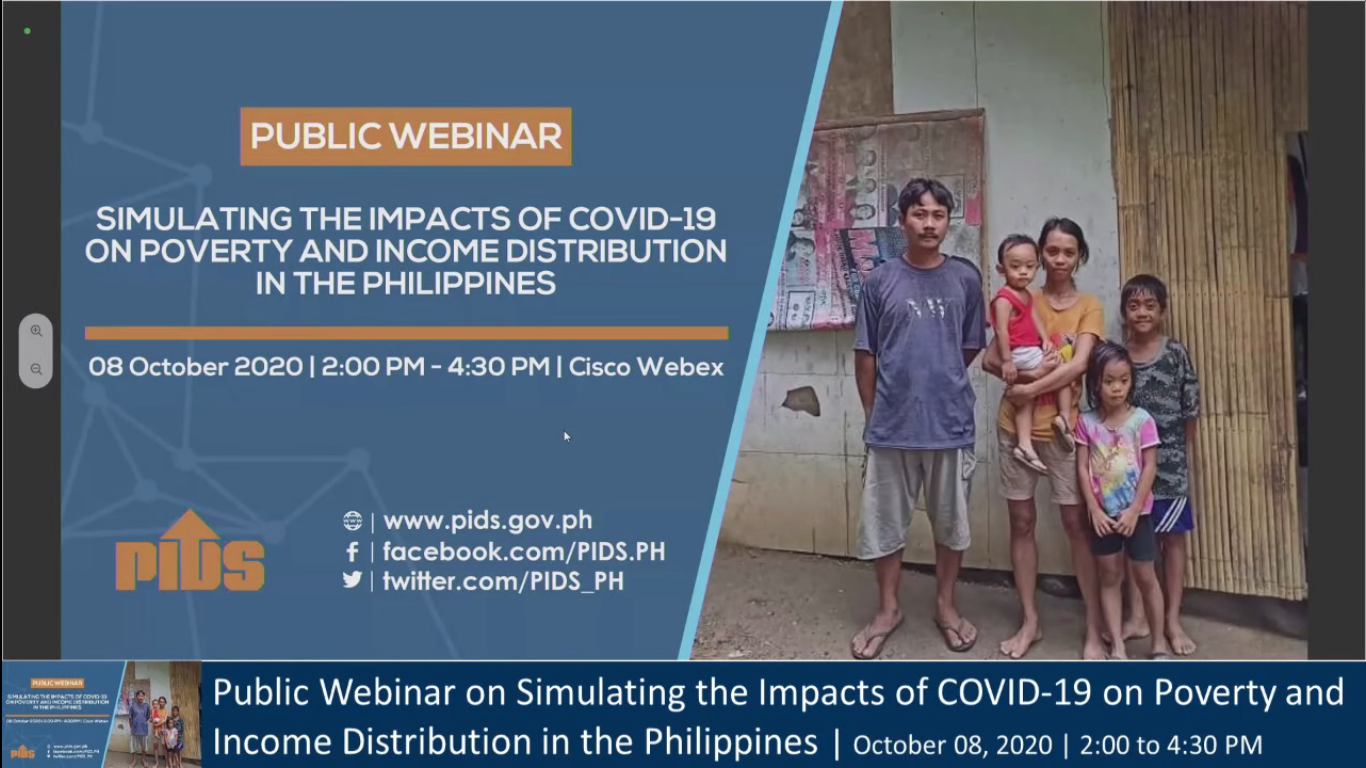

On top of an economic recession and temporary unemployment, the COVID-19 pandemic is seen inflicting a bigger damage on the Philippines’ goal to reduce poverty and become a middle-class society by 2040, the state-run think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) said.

“Given the likely drop in incomes and expenditures of households as well as businesses, we would expect a worsening of poverty conditions” due to the prolonged lockdown, authors Jose Ramon G. Albert, Michael Ralph M. Abrigo, Francis Mark A. Quimba and Jana Flor V. Vizmanos said in a PIDS discussion paper titled “Poverty, the Middle Class, and Income Distribution amid COVID-19” published on Tuesday.

Based on the researchers’ simulation of COVID-19’s impact, poverty conditions could revert to the level seen more than a decade ago and targets for the country to attain its aspirations to become a largely middle-class society could be pushed back.

The government’s AmBisyon Natin 2040 aims at tripling Filipinos’ per capita income to $11,000 in 20 years’ time by sustaining at least 6.5-percent annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth alongside the implementation of policies that would make the Philippines a high-income country by 2040.

President Duterte adopted AmBisyon Natin 2040 as the long-term vision for the country such that 20 years from now, “the Philippines shall be a prosperous, predominantly middle-class society where no one is poor.”

A survey conducted in 2016 showed that the majority of Filipinos aspire for a “simple and comfortable life,” which the state planning agency National Economic and Development Authority (Neda) had said reflected middle-class lifestyle—earning enough, educating all children until college, owning a car, owning a medium-sized house, finding time to relax with family and friends, owning a business and being able to travel around the country.

A deterrent to the AmBisyon Natin 2040 vision was the likelihood that millions of Filipinos could slide back to poverty as a result of joblessness and a COVID-19-induced recession.

In particular, the PIDS paper said that the number of poor Filipinos could rise by about 1.5 million from the baseline figures, if everyone’s incomes contract by 10 percent, even with the SAP (social amelioration program) and SBWS (small business wage subsidy) in place, referring to the dole-outs given away to poor families and displaced workers of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) at the height of the COVID-19 lockdown, during which 75 percent of the economy stopped and rendered 7.5 million Filipinos jobless.

“Without SAP and SBWS, the number of poor would rise even by 5.5 million,” the PIDS paper added.

In 2018, poverty incidence fell to 16.7 percent from 23.3 percent in 2015, which translated to almost six million Filipinos lifted out of poverty.

The government targets to slash the poverty rate to 11 percent by 2022.

For PIDS, “the government and all Filipinos should ultimately ensure that the poor are at the center of policy attention, especially given all the reduced economic activities from COVID-19 and the likely undercounts of COVID-19 infection among the poor, who do not have the luxury to seek health care, and for whom ‘washing hands’ is also a luxury (as they have no access to safe water and safe sanitation services).”

“The poor as well as certain other nonpoor groups (the low income but not poor, and the lower middle-income group) are vulnerable from both the public-health challenges of the COVID-19 and the economic consequences of efforts to contain the virus. These vulnerable groups often have meager savings to cushion them against sustained economic disruptions, and may have even little protection against other related shocks, such as job losses, and food insecurity. Their recovery may be challenging compared to those in higher income groups,” according to PIDS. INQ

“Given the likely drop in incomes and expenditures of households as well as businesses, we would expect a worsening of poverty conditions” due to the prolonged lockdown, authors Jose Ramon G. Albert, Michael Ralph M. Abrigo, Francis Mark A. Quimba and Jana Flor V. Vizmanos said in a PIDS discussion paper titled “Poverty, the Middle Class, and Income Distribution amid COVID-19” published on Tuesday.

Based on the researchers’ simulation of COVID-19’s impact, poverty conditions could revert to the level seen more than a decade ago and targets for the country to attain its aspirations to become a largely middle-class society could be pushed back.

The government’s AmBisyon Natin 2040 aims at tripling Filipinos’ per capita income to $11,000 in 20 years’ time by sustaining at least 6.5-percent annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth alongside the implementation of policies that would make the Philippines a high-income country by 2040.

President Duterte adopted AmBisyon Natin 2040 as the long-term vision for the country such that 20 years from now, “the Philippines shall be a prosperous, predominantly middle-class society where no one is poor.”

A survey conducted in 2016 showed that the majority of Filipinos aspire for a “simple and comfortable life,” which the state planning agency National Economic and Development Authority (Neda) had said reflected middle-class lifestyle—earning enough, educating all children until college, owning a car, owning a medium-sized house, finding time to relax with family and friends, owning a business and being able to travel around the country.

A deterrent to the AmBisyon Natin 2040 vision was the likelihood that millions of Filipinos could slide back to poverty as a result of joblessness and a COVID-19-induced recession.

In particular, the PIDS paper said that the number of poor Filipinos could rise by about 1.5 million from the baseline figures, if everyone’s incomes contract by 10 percent, even with the SAP (social amelioration program) and SBWS (small business wage subsidy) in place, referring to the dole-outs given away to poor families and displaced workers of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) at the height of the COVID-19 lockdown, during which 75 percent of the economy stopped and rendered 7.5 million Filipinos jobless.

“Without SAP and SBWS, the number of poor would rise even by 5.5 million,” the PIDS paper added.

In 2018, poverty incidence fell to 16.7 percent from 23.3 percent in 2015, which translated to almost six million Filipinos lifted out of poverty.

The government targets to slash the poverty rate to 11 percent by 2022.

For PIDS, “the government and all Filipinos should ultimately ensure that the poor are at the center of policy attention, especially given all the reduced economic activities from COVID-19 and the likely undercounts of COVID-19 infection among the poor, who do not have the luxury to seek health care, and for whom ‘washing hands’ is also a luxury (as they have no access to safe water and safe sanitation services).”

“The poor as well as certain other nonpoor groups (the low income but not poor, and the lower middle-income group) are vulnerable from both the public-health challenges of the COVID-19 and the economic consequences of efforts to contain the virus. These vulnerable groups often have meager savings to cushion them against sustained economic disruptions, and may have even little protection against other related shocks, such as job losses, and food insecurity. Their recovery may be challenging compared to those in higher income groups,” according to PIDS. INQ